October Revolution

The provisional government remained unpopular, especially because it was continuing to fight in World War I, and had ruled with an iron fist throughout mid-1917 (including killing hundreds of protesters in the July Days).

October Revolution Day was a public holiday in the Soviet Union, marking its key role in the state's founding, and many communist parties around the world celebrate it.

[14] Initially the event was referred to as the "October coup" (Октябрьский переворот) or the "Uprising of the 3rd", as seen in contemporary documents, for example in the first editions of Lenin's complete works.

In September, the garrisons in Petrograd, Moscow, and other cities, the Northern and Western fronts, and the sailors of the Baltic Fleet declared through their elected representative body Tsentrobalt that they did not recognize the authority of the Provisional Government and would not carry out any of its commands.

"[20] In a diplomatic note of 1 May, the minister of foreign affairs, Pavel Milyukov, expressed the Provisional Government's desire to continue the war against the Central Powers "to a victorious conclusion", arousing broad indignation.

The Provisional Government, with the support of Socialist-Revolutionary Party-Menshevik leaders of the All-Russian Executive Committee of the Soviets, ordered an armed attack against the demonstrators, killing hundreds.

The committee methodically planned to occupy strategic locations through the city, almost without concealing their preparations: the Provisional Government's President Kerensky was himself aware of them; and some details, leaked by Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev, were published in newspapers.

What followed was a series of sporadic clashes over control of the bridges, between Red Guard militias aligned with the Military-Revolutionary Committee and military units still loyal to the government.

In the early morning, from its heavily guarded and picketed headquarters in Smolny Palace, the Military-Revolutionary Committee designated the last of the locations to be assaulted or seized.

On the morning of the insurrection, Kerensky desperately searched for a means of reaching military forces he hoped would be friendly to the Provisional Government outside the city and ultimately borrowed a Renault car from the American embassy, which he drove from the Winter Palace, along with a Pierce Arrow.

One of Lenin's intentions was to present members of the Soviet congress, who would assemble that afternoon, with a fait accompli and thus forestall further debate on the wisdom or legitimacy of taking power.

These are disputed by various sources, such as Louise Bryant,[42] who claims that news outlets in the West at the time reported that the unfortunate loss of life occurred in Moscow, not Petrograd, and the number was much less than suggested above.

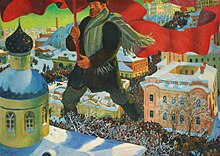

This reenactment, watched by 100,000 spectators, provided the model for official films made later, which showed fierce fighting during the storming of the Winter Palace,[45] although, in reality, the Bolshevik insurgents had faced little opposition.

Retrospectively, Lenin's primary associates such as Zinoviev, Trotsky, Radek and Bukharin were presented as "vacillating", "opportunists" and "foreign spies" whereas Stalin was depicted as the chief discipline during the revolution.

[48] In his book, The Stalin School of Falsification, Leon Trotsky argued that the Stalinist faction routinely distorted historical events and the importance of Bolshevik figures especially during the October Revolution.

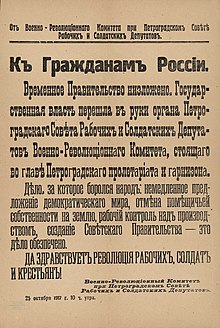

[54] When the fall of the Winter Palace was announced, the Congress adopted a decree transferring power to the Soviets of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies, thus ratifying the Revolution.

That same day, posters were pinned on walls and fences by the Socialist Revolutionaries, describing the takeover as a "crime against the motherland" and "revolution"; this signaled the next wave of anti-Bolshevik sentiment.

After the fall of Moscow, there was only minor public anti-Bolshevik sentiment, such as the newspaper Novaya Zhizn, which criticized the Bolsheviks' lack of manpower and organization in running their party, let alone a government.

To establish the accuracy of Marxist ideology, Soviet historians generally described the Revolution as the product of class struggle and that it was the supreme event in a world history governed by historical laws.

Guided by Lenin's leadership and his firm grasp of scientific Marxist theory, the Party led the "logically predetermined" events of the October Revolution from beginning to end.

Following Stalin's death, historians such as E. N. Burdzhalov and P. V. Volobuev published historical research that deviated significantly from the party line in refining the doctrine that the Bolshevik victory "was predetermined by the state of Russia's socio-economic development".

[78] These historians, who constituted the "New Directions Group", posited that the complex nature of the October Revolution "could only be explained by a multi-causal analysis, not by recourse to the mono-causality of monopoly capitalism".

[83] Other analyses following this "anthropological turn" have explored texts from soldiers and how they used personal war-experiences to further their political goals,[84] as well as how individual life-structure and psychology may have shaped major decisions in the civil war that followed the revolution.

Examples of these accidental and contingent factors they say precipitated the Revolution included World War I's timing, chance, and the poor leadership of Tsar Nicholas II as well as that of liberal and moderate socialists.

According to Evan Mawdsley, "the 'revisionist’ school had been dominant from the 1970s" in academic circles, and achieved "some success" in challenging the traditionalists;[88] however, they continued to be criticized by "totalitarians" who accused them of "Marxism" and failing to see the primary reason of political events, the personality of the leaders.

During the rise of the "revisionists", "totalitarians" retained popularity and influence outside academic circles, especially in politics and public spheres of the United States, where they supported harder policies towards the USSR: for example, Zbigniew Brzezinski served as National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter, while Richard Pipes headed the CIA group Team B; after 1991, their views have found popularity not only in the West, but also in the former USSR.

While the disintegration essentially helped solidify the Western and Revisionist views, post-USSR Russian historians largely repudiated the former Soviet historical interpretation of the Revolution.

Ten Days That Shook the World, a book written by American journalist John Reed and first published in 1919, gives a firsthand exposition of the events.

Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov's film October: Ten Days That Shook the World, first released on 20 January 1928 in the USSR and on 2 November 1928 in New York City, describes and glorifies the revolution, having been commissioned to commemorate the event.

The date 7 November, the anniversary of the October Revolution according to the Gregorian Calendar, was the official national day of the Soviet Union from 1918 onward and still is a public holiday in Belarus and the breakaway territory of Transnistria.