Bombe

The bombe (UK: /bɒmb/) was an electro-mechanical device used by British cryptologists to help decipher German Enigma-machine-encrypted secret messages during World War II.

[1] The US Navy[2] and US Army[3] later produced their own machines to the same functional specification, albeit engineered differently both from each other and from Polish and British bombes.

The initial design of the British bombe was produced in 1939 at the UK Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park by Alan Turing,[4] with an important refinement devised in 1940 by Gordon Welchman.

The first bombe, code-named Victory, was installed in March 1940[6] while the second version, Agnus Dei or Agnes, incorporating Welchman's new design, was working by August 1940.

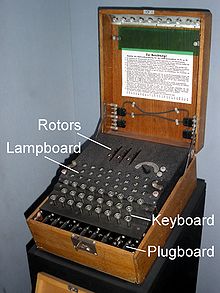

The repeated changes of the electrical pathway from the keyboard to the lampboard implement a polyalphabetic substitution cipher, which turns plaintext into ciphertext and back again.

[17] An important feature of the machine from a cryptanalyst's point of view, and indeed Enigma's Achilles' heel, was that the reflector in the scrambler prevented a letter from being enciphered as itself.

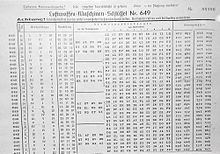

[23] In the words of Gordon Welchman, "... the task of the bombe was simply to reduce the assumptions of wheel order and scrambler positions that required 'further analysis' to a manageable number".

From there, the circuit continued to a plugboard located on the left-hand end panel, which was wired to imitate an Enigma reflector and then back through the outer pair of contacts.

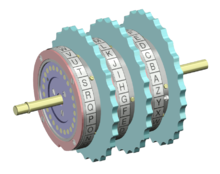

[25][26] The drums were colour-coded according to which Enigma rotor they emulated: I red; II maroon; III green; IV yellow; V brown; VI cobalt (blue); VII jet (black); VIII silver.

This progressively eliminated the false stops, built up the set of plugboard connections and established the positions of the rotor alphabet rings.

Looking at position 10 of the crib:ciphertext comparison, we observe that A encrypts to T, or, expressed as a formula: Due to the function P being its own inverse, we can apply it to both sides of the equation and obtain the following: This gives us a relationship between P(A) and P(T).

This means that the initial assumption must have been incorrect, and so that (for this rotor setting) P(A) ≠ Y (this type of argument is termed reductio ad absurdum or "proof by contradiction").

To form this circuit, the bombe used several sets of Enigma rotor stacks wired up together according to the instructions given on a menu, derived from a crib.

While Turing's bombe worked in theory, it required impractically long cribs to rule out sufficiently large numbers of settings.

The bomby were delivered in November 1938, but barely a month later the Germans introduced two additional rotors for loading into the Enigma scrambler, increasing the number of wheel orders by a factor of ten.

Alan Turing designed the British bombe on a more general principle, the assumption of the presence of text, called a crib, that cryptanalysts could predict was likely to be present at a defined point in the message.

[37] Bletchley retrospectively attacked some messages sent during this period using the captured material and an ingenious Bombe menu where the Enigma fast rotors were all in the same position.

[46] Production of bombes by BTM at Letchworth in wartime conditions was nowhere near as rapid as the Americans later achieved at NCR in Dayton, Ohio.

One, code-named Cobra, with an electronic sensing unit, was produced by Charles Wynn-Williams of the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) at Malvern and Tommy Flowers of the General Post Office (GPO).

After considerable internal rivalry and dispute, Gordon Welchman (by then, Bletchley Park's Assistant Director for mechanisation) was forced to step in to resolve the situation.

Despite some worthwhile collaboration amongst the cryptanalysts, their superiors took some time to achieve a trusting relationship in which both British and American bombes were used to mutual benefit.

Colonel John Tiltman, who later became Deputy Director at Bletchley Park, visited the US Navy cryptanalysis office (OP-20-G) in April 1942 and recognised America's vital interest in deciphering U-boat traffic.

The urgent need, doubts about the British engineering workload and slow progress, prompted the US to start investigating designs for a Navy bombe, based on the full blueprints and wiring diagrams received by US Naval Lieutenants Robert Ely and Joseph Eachus at Bletchley Park in July 1942.

Commander Edward Travis, Deputy Director and Frank Birch, Head of the German Naval Section travelled from Bletchley Park to Washington in September 1942.

With Carl Frederick Holden, US Director of Naval Communications they established, on 2 October 1942, a UK:US accord which may have "a stronger claim than BRUSA to being the forerunner of the UKUSA Agreement," being the first agreement "to establish the special Sigint relationship between the two countries," and "it set the pattern for UKUSA, in that the United States was very much the senior partner in the alliance.

"[65] It established a relationship of "full collaboration" between Bletchley Park and OP-20-G.[16] An all electronic solution to the problem of a fast bombe was considered,[16] but rejected for pragmatic reasons, and a contract was let with the National Cash Register Corporation (NCR) in Dayton, Ohio.

Alan Turing, who had written a memorandum to OP-20-G (probably in 1941),[66] was seconded to the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington in December 1942, because of his exceptionally wide knowledge about the bombes and the methods of their use.

When the Americans began to turn out bombes in large numbers there was a constant interchange of signal - cribs, keys, message texts, cryptographic chat and so on.

[69] In 1994 a group led by John Harper of the BCS Computer Conservation Society started a project to build a working replica of a bombe.

[77] The project required detailed research, and took thirteen years of effort before the replica was completed, which was then put on display at the Bletchley Park museum.