Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

[11] This was to be followed in March 1946 by Operation Coronet, the capture of the Kantō Plain, near Tokyo on the main Japanese island of Honshu by the U.S. First, Eighth and Tenth Armies, as well as a Commonwealth Corps made up of Australian, British and Canadian divisions.

[24] This effort failed to achieve the strategic objectives that its planners had intended, largely because of logistical problems, the bomber's mechanical difficulties, the vulnerability of Chinese staging bases, and the extreme range required to reach key Japanese cities.

[53] Progress was slow until the arrival of the British MAUD Committee report in late 1941, which indicated that only 5 to 10 kilograms of isotopically-pure uranium-235 were needed for a bomb instead of tons of natural uranium and a neutron moderator like heavy water.

These aircraft were specially adapted to carry nuclear weapons, and were equipped with fuel-injected engines, Curtiss Electric reversible-pitch propellers, pneumatic actuators for rapid opening and closing of bomb bay doors and other improvements.

[95] Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland Wilson announced that the British government concurred with the use of nuclear weapons against Japan, which would be officially recorded as a decision of the Combined Policy Committee.

[108] Responding to concerns expressed by the 509th Composite Group about the possibility of a B-29 crashing on takeoff, Birch had modified the Little Boy design to incorporate a removable breech plug that would permit the bomb to be armed in flight.

[107] The first plutonium core, along with its polonium-beryllium urchin initiator, was transported in the custody of Project Alberta courier Raemer Schreiber in a magnesium field carrying case designed for the purpose by Philip Morrison.

Three Fat Man high-explosive pre-assemblies, designated F31, F32, and F33, were picked up at Kirtland on 28 July by three B-29s, two from the 393rd Bombardment Squadron plus one from the 216th Army Air Force Base Unit, and transported to North Field, arriving on 2 August.

As the numerous small fires created by the blast began to grow, they merged into a firestorm that moved quickly throughout the ruins, killing many who had been trapped, and causing people to jump into Hiroshima's rivers in search of sanctuary (many of whom drowned).

Since the bomb detonated in the air, the blast was directed more downward than sideways, which was largely responsible for the survival of the Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall, now commonly known as the Genbaku (A-bomb) dome, which was only 150 m (490 ft) from ground zero (the hypocenter).

The ruin was named Hiroshima Peace Memorial and was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996 over the objections of the United States and China, which expressed reservations on the grounds that other Asian nations were the ones who suffered the greatest loss of life and property, and a focus on Japan lacked historical perspective.

Yoshie Oka, a Hijiyama Girls High School student who had been mobilized to serve as a communications officer, had just sent a message that the alarm had been issued for Hiroshima and neighboring Yamaguchi, when the bomb exploded.

The senior leadership of the Japanese Army began preparations to impose martial law on the nation, with the support of Minister of War Korechika Anami, to stop anyone attempting to make peace.

[187][186] The city of Nagasaki had been one of the largest seaports in southern Japan, and was of great wartime importance because of its wide-ranging industrial activity, including the production of ordnance, ships, military equipment, and other war materials.

Nagasaki had been permitted to grow for many years without conforming to any definite city zoning plan; residences were erected adjacent to factory buildings and to each other almost as closely as possible throughout the entire industrial valley.

[195][196] This time Penney and Cheshire were allowed to accompany the mission, flying as observers on the third plane, Big Stink, flown by the group's operations officer, Major James I. Hopkins, Jr.

[194] According to Cheshire, Hopkins was at varying heights including 2,700 meters (9,000 ft) higher than he should have been, and was not flying tight circles over Yakushima as previously agreed with Sweeney and Captain Frederick C. Bock, who was piloting the support B-29 The Great Artiste.

No consensus had emerged by 02:00 on 10 August, but the emperor gave his "sacred decision",[238] authorizing the Foreign Minister, Shigenori Tōgō, to notify the Allies that Japan would accept their terms on one condition, that the declaration "does not comprise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign ruler.

"[240] As the Allied terms seemed to leave intact the principle of the preservation of the Throne, Hirohito recorded on 14 August his capitulation announcement which was broadcast to the Japanese nation the next day despite an attempted military coup d'état by militarists opposed to the surrender.

Despite the best that has been done by every one—the gallant fighting of military and naval forces, the diligence and assiduity of Our servants of the State and the devoted service of Our one hundred million people, the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan's advantage, while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest.The sixth paragraph by Hirohito specifically mentions the use of nuclear ordnance devices, from the aspect of the unprecedented damage they caused: Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives.

Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.The seventh paragraph gives the reason for the ending of hostilities against the Allies: Such being the case, how are we to save the millions of our subjects, or to atone ourselves before the hallowed spirits of our imperial ancestors?

[242]In his "Rescript to the Soldiers and Sailors" delivered on 17 August, Hirohito did not refer to the atomic bombs or possible human extinction, and instead described the Soviet declaration of war as "endangering the very foundation of the Empire's existence.

"[243] On 10 August 1945, the day after the Nagasaki bombing, military photographer Yōsuke Yamahata, correspondent Higashi, and artist Yamada arrived in the city with instructions to record the destruction for propaganda purposes.

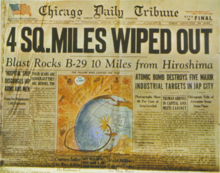

[247] The New York Times then apparently reversed course and ran a front-page story by Bill Lawrence confirming the existence of a terrifying affliction in Hiroshima, where many had symptoms such as hair loss and vomiting blood before dying.

[254] The public release of film footage of the city post-attack, and some research about the effects of the attack, was restricted during the occupation of Japan,[255] but the Hiroshima-based magazine, Chugoku Bunka, in its first issue published on 10 March 1946, devoted itself to detailing the damage from the bombing.

[256] The book Hiroshima, written by Pulitzer Prize winner John Hersey and originally published in article form in The New Yorker,[257] is reported to have reached Tokyo in English by January 1947, and the translated version was released in Japan in 1949.

[270] Conventional skin injuries that cover a large area frequently result in bacterial infection; the risk of sepsis and death is increased when a usually non-lethal radiation dose moderately suppresses the white blood cell count.

[271] In the spring of 1948, the ABCC was established in accordance with a presidential directive from Truman to the National Academy of Sciences–National Research Council to conduct investigations of the late effects of radiation among the survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

[329][330] A view among critics of the bombings, popularized by American historian Gar Alperovitz in 1965, is that the United States used nuclear weapons to intimidate the Soviet Union in the early stages of the Cold War.

[332] This means that aerial bombardment of civilian areas in enemy territory by all major belligerents during World War II was not prohibited by positive or specific customary international humanitarian law.

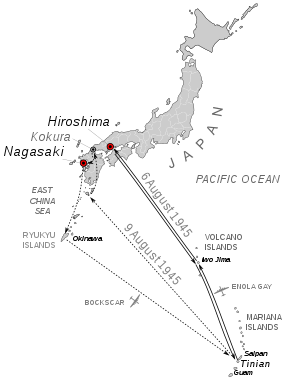

White and green: Areas controlled by Japan

Red: Areas controlled by the Allies

Gray: Areas controlled by the Soviet Union (neutral)