Molecular geometry

Molecular geometry influences several properties of a substance including its reactivity, polarity, phase of matter, color, magnetism and biological activity.

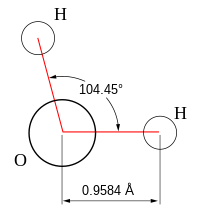

[1][2][3] The angles between bonds that an atom forms depend only weakly on the rest of molecule, i.e. they can be understood as approximately local and hence transferable properties.

IR, microwave and Raman spectroscopy can give information about the molecule geometry from the details of the vibrational and rotational absorbance detected by these techniques.

Geometries can also be computed by ab initio quantum chemistry methods to high accuracy.

The overall (external) quantum mechanical motions translation and rotation hardly change the geometry of the molecule.

(To some extent rotation influences the geometry via Coriolis forces and centrifugal distortion, but this is negligible for the present discussion.)

The molecular vibrations are harmonic (at least to good approximation), and the atoms oscillate about their equilibrium positions, even at the absolute zero of temperature.

At absolute zero all atoms are in their vibrational ground state and show zero point quantum mechanical motion, so that the wavefunction of a single vibrational mode is not a sharp peak, but approximately a Gaussian function (the wavefunction for n = 0 depicted in the article on the quantum harmonic oscillator).

At 298 K (25 °C), typical values for the Boltzmann factor β are: (The reciprocal centimeter is an energy unit that is commonly used in infrared spectroscopy; 1 cm−1 corresponds to 1.23984×10−4 eV).

But, as a quantum mechanical motion, it is thermally excited at relatively (as compared to vibration) low temperatures.

In quantum mechanical language: more eigenstates of higher angular momentum become thermally populated with rising temperatures.