Bone Wars

Cope and Marsh were financially and socially ruined by their attempts to outcompete and disgrace each other, but they made important contributions to science and the field of paleontology and provided substantial material for further work—both scientists left behind many unopened boxes of fossils after their deaths.

The products of the Bone Wars resulted in an increase in knowledge of prehistoric life, and sparked the public's interest in dinosaurs, leading to continued fossil excavation in North America in the decades to follow.

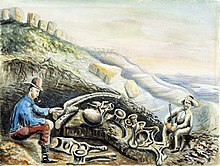

[5] In 1864, already a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Cope became a professor of zoology at Haverford College and joined Ferdinand Hayden on his expeditions west.

In contrast, Marsh would have grown up poor, the son of a struggling family in Lockport, New York, had it not been for the benefaction of his uncle, philanthropist George Peabody.

[8] Marsh humiliated Cope by pointing out that his reconstruction of the plesiosaur Elasmosaurus was flawed, with the head placed where the tail should have been (or so he claimed, 20 years later;[9] it was Leidy who published the correction shortly afterwards).

[13] Believing he had the full support of Hayden and the survey, Cope then traveled to Fort Bridger in June, only to find that the men, wagons, horses, and equipment he expected were not there.

[24] The two scientists' attention turned to the Dakota Territory in the mid-1870s, where the discovery of gold in the Black Hills increased Native American tensions with the United States.

In the end, Marsh slipped out of camp and according to his own (possibly romanticized) accounts, amassed cartloads of fossils and retreated just before a hostile Miniconjou party arrived.

[27] By 1875, both Cope and Marsh paused in their collecting, feeling financial strain and needing to catalogue their backlogged finds, but new discoveries would return them to the West before decade's end.

After receiving more samples from Lucas, Cope concluded the dinosaurs were large herbivores, gleefully noting that the specimen was larger than any other previously described, including Lakes' discovery.

[36] Wary of repeating the same mistakes he had made with Lakes, Marsh quickly sent money to the two new bone hunters and urged them to send additional fossils.

[37] Marsh drew up a contract calling for a set monthly fee, with additional cash bonuses to Carlin and Reed possible, depending on the importance of the finds.

The paleontologist procured Carlin's and Reed's services, but seeds of resentment were sown as the bone hunters felt Marsh had bullied them into the deal.

[40] Marsh, attempting to cover the leak, learned from Williston that Carlin and Reed had been visited by a man ostensibly working for Cope by the name of "Haines".

[40] After learning of the Como Bluff discoveries, Cope sent "dinosaur rustlers" to the area in an attempt to quietly steal fossils from under Marsh's nose.

Although Marsh's men continued to open new quarries and discover more fossils, relations between Lakes and Reed soured, with each offering his resignation in August.

Professor Alexander Emanuel Agassiz of Harvard sent his own representatives west, while Carlin and Frank Williston formed a bone company to sell fossils to the highest bidder.

The two men were so protective of their digging sites that they would destroy smaller or damaged fossils to prevent them from falling into their rival's hands, or fill in their excavations with dirt and rock;[50] while surveying his Como quarries in 1879, Marsh examined recent finds and marked several for destruction.

[54] Cope was much less well-off, having spent most of his money purchasing The American Naturalist, and had a hard time finding employment thanks to Marsh's allies in higher education and his own temperament.

[54][55] Cope began investing in gold and silver prospects in the West, and braved malarial mosquitos and harsh weather to search for fossils himself.

[56] Due to mining setbacks and a lack of support from the federal government,[11] Cope's financial situation deteriorated to the point that his fossil collection was his only significant asset.

Marsh, meanwhile, alienated even his loyal assistants, including Williston, with his refusal to share his conclusions drawn from their findings, and his continually lax and infrequent payment schedule.

[60] Osborn seemed reluctant to step up his campaign against Marsh, so Cope turned to another ally he had mentioned to Osborn—a "newspaper man from New York" named William Hosea Ballou.

[61][62] Despite setbacks in trying to oust Marsh from his presidency of the National Academy of Sciences,[63] Cope received a tremendous financial boost after the University of Pennsylvania offered him a teaching job.

[62] While the scientific community had long known of Marsh and Cope's rivalry, the public became aware of the shameful conduct of the two men when the New York Herald published a story with the headline "Scientists Wage Bitter Warfare.

Towards the latter part of the decade, Cope's fortunes began to sour once more as Marsh regained some of his recognition, earning the Cuvier Medal, the highest paleontological award.

Cope suffered from a debilitating illness in his later years and had to sell part of his fossil collection and rent out one of his houses to make ends meet.

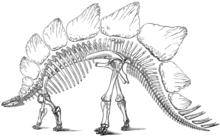

[77] Several of Cope's and Marsh's discoveries are among the most well-known of dinosaurs, encompassing species of Triceratops, Allosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus, Camarasaurus and Coelophysis.

Furthermore, the reported use of dynamite and sabotage by employees of both men may have harmed fossil remains,[4] though later excavation suggests that some of the damage was exaggerated in order to dissuade competition.

[4] Leidy also grew tired of the constant squabbling between the two men, with the result that his withdrawal from the field marginalized his own legacy; after his death, Osborn found not a single mention of the man in either of the rivals' works.