Elasmosaurus

Cope originally reconstructed the skeleton of Elasmosaurus with the skull at the end of the tail, an error which was made light of by the paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, and became part of their "Bone Wars" rivalry.

Measuring 10.3 meters (34 ft) in length, Elasmosaurus would have had a streamlined body with paddle-like limbs, a short tail, a small head, and an extremely long neck.

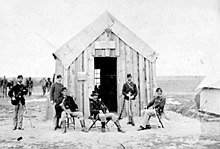

Approximately 23 kilometers (14 mi) northeast of Fort Wallace, near McAllaster, Turner discovered the bones of a large fossil reptile in a ravine in the Pierre Shale formation, and though he had no paleontological experience, he recognized the remains as belonging to an "extinct monster".

[2][3][4] In December 1867 Turner and others from Fort Wallace returned to the site and recovered much of the vertebral column, as well as concretions that contained other bones; the material had a combined weight of 360 kilograms (800 lb).

[2] In 1869 Cope scientifically described and figured Elasmosaurus, and the preprint version of the manuscript contained a reconstruction of the skeleton which he had earlier presented during his report at an ANSP meeting in September 1868.

[7][8][9][3] To hide his mistake, Cope attempted to recall all copies of the preprint article, and printed a corrected version with a new skeletal reconstruction that placed the head on the neck (though it reversed the orientation of the individual vertebrae) and different wording in 1870.

In 2002 the American art historian Jane P. Davidson noted that the fact that other scientists early on had pointed out Leidy's error argues against this explanation, adding that Cope was not convinced he had made a mistake.

[3] Though Cope described and figured the pectoral and pelvic girdles of Elasmosaurus in 1869 and 1875, these elements were noted as missing from the collection by the American paleontologist Samuel Wendell Williston in 1906.

At the time, Hawkins was working on a "Paleozoic Museum" in New York's Central Park, where a reconstruction of Elasmosaurus was to appear, an American equivalent to his life-sized Crystal Palace Dinosaurs in London.

[2][3][16][17][18] In 2018, Davidson and Everhart documented the events leading up to the disappearance of these fossils, and suggested that a photo and drawing of Waterhouse's workshop from 1869 appear to show concretions on the floor that may have been the unprepared girdles of Elasmosaurus.

[19] In 2007 the Colombian paleontologists Leslie Noè and Marcela Gómez-Pérez expressed doubt that the additional elements belonged to the type specimen, or even to Elasmosaurus, due to lack of evidence.

[20] In 2017 Sachs and Joachim Ladwig suggested that a fragmentary elasmosaurid skeleton from the upper Campanian of Kronsmoor in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, and housed in the Naturkunde-Museum Bielefeld, may have belonged to Elasmosaurus.

[22][2] The pectoral and pelvic girdles of the holotype specimen were noted as missing by 1906, but observations about these elements were since made based on the original descriptions and figures from the late 19th century.

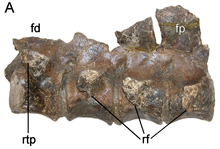

The articular surfaces of the vertebrae in the front of the neck were broad oval, and moderately deepened, with rounded, thickened edges, with an excavation (or cavity) at the upper and lower sides.

The rib facets of the pectoral vertebrae were triangular in shape and situated on transverse processes, and the centra bore pairs of nutritive foramina in the middle of the lower sides.

However, none of these species are still definitely referable to the genus Elasmosaurus today, and most of them either have been moved to genera of their own or are considered dubious names, nomina dubia – that is, with no distinguishing features, and therefore of questionable validity.

[28] He distinguished E. orientalis from E. platyurus by the more strongly developed processes known as parapophyses on the vertebrae, in which he considered it to approach closer to Cimoliasaurus; however, he still assigned it to Elasmosaurus on account of its large size and angled sides.

[31] In the same 1869 publication wherein he named E. platyurus and E. orientalis, Cope assigned an additional species, E. constrictus,[7] based on a partial centrum from a neck vertebra found in the Turonian-aged clay deposits at Steyning, Sussex, in the United Kingdom.

[38] Kenneth Carpenter reassigned it to Thalassomedon haningtoni in 1999;[26] Sachs, Johan Lindgren, and Benjamin Kear noted that the remains represented a juvenile and were significantly distorted, and preferred to retain it as a nomen dubium in 2016.

[42] Subsequently, a series of 19 neck and back vertebrae from the Big Bend region of the Missouri – part of the Pierre Shale formation – were found by John H. Charles.

He characterized elasmosaurids by their long necks and small heads, as well as by their rigid and well-developed scapulae (but atrophied or absent clavicles and interclavicles) for forelimb-driven locomotion.

The cited variability in the number of heads on the neck ribs arises from his inclusion of Simolestes to the Elasmosauridae, since the characteristics of "both the skull and shoulder girdle compare more favorably with Elasmosaurus than with Pliosaurus or Peloneustes."

[83] Topology A: Benson et al. (2013)[77] Cryptoclididae Leptocleididae Polycotylidae Thalassomedon Libonectes Elasmosaurus Terminonatator Styxosaurus Hydrotherosaurus Callawayasaurus Eromangasaurus Kaiwhekea Aristonectes Topology B: Otero (2016),[39] with clade names following O'Gorman (2020)[83] Cryptoclididae Leptocleididae Polycotylidae Eromangasaurus Callawayasaurus Libonectes Tuarangisaurus Thalassomedon Specimen CM Zfr 115 Hydrotherosaurus Futabasaurus Kaiwhekea Alexandronectes Morturneria Aristonectes Terminonatator Elasmosaurus Albertonectes Styxosaurus

[22] The unusual body structure of elasmosaurids would have limited the speed at which they could swim, and their paddles may have moved in a manner similar to the movement of oars rowing, and due to this, could not twist and were thus held rigidly.

Although he suggested that the vertebral column of the trunk did not allow for much vertical movement due to the elongated neural spines which nearly form a continuous line with little space between adjacent vertebrae, he envisaged the neck and tail to have been much more flexible: "The snake-like head was raised high in the air, or depressed at the will of the animal, now arched swan-like preparatory to a plunge after a fish, now stretched in repose on the water or deflexed in exploring the depths below".

Elasmosaurids may also have been active hunters in the pelagic zone, retracting their necks to launch a strike or using side-swipe motions to stun or kill prey with their laterally projected teeth (like sawsharks).

[100] Elasmosaurus is known from the Sharon Springs Member of the Campanian-age Upper Cretaceous Pierre Shale formation of western Kansas, which dates to about 80.64 to 77 million years ago.

[101] The Pierre Shale represents a period of marine deposition from the Western Interior Seaway, a shallow continental sea that submerged much of central North America during the Cretaceous.

Two great continental watersheds drained into it from east and west, diluting its waters and bringing resources in eroded silt that formed shifting river delta systems along its low-lying coasts.

[107] In addition to Elasmosaurus, other marine reptiles present include fellow plesiosaurs Libonectes, Styxosaurus, Thalassomedon, Terminonatator, Polycotylus, Brachauchenius, Dolichorhynchops and Trinacromerum;[108] the mosasaurs Mosasaurus, Halisaurus, Prognathodon, Tylosaurus, Ectenosaurus, Globidens, Clidastes, Platecarpus and Plioplatecarpus;[109] and the sea turtles Archelon, Protostega, Porthochelys and Toxochelys.