Acts of the Apostles

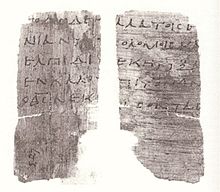

The Acts of the Apostles[a] (Koinē Greek: Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, Práxeis Apostólōn;[2] Latin: Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its message to the Roman Empire.

[5] The first part, the Gospel of Luke, tells how God fulfilled his plan for the world's salvation through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth.

The later chapters narrate the continuation of the message under Paul the Apostle and concludes with his imprisonment in Rome, where he awaits trial.

"[12] He was educated, a man of means, probably urban, and someone who respected manual work, although not a worker himself; this is significant, because more high-brow writers of the time looked down on the artisans and small business people who made up the early church of Paul and were presumably Luke's audience.

[13] The interpretation of the "we" passages as indicative that the writer was a historical eyewitness (whether Luke the evangelist or not), remains the most influential in current biblical studies.

[14] Objections to this viewpoint include the above claim that Luke-Acts contains differences in theology and historical narrative which are irreconcilable with the authentic letters of Paul the Apostle.

[2] The anonymous author aligned Luke–Acts to the 'narratives' (διήγησις diēgēsis) which many others had written, and described his own work as an "orderly account" (ἀκριβῶς καθεξῆς).

The mid-19th-century scholar Ferdinand Baur suggested that the author had re-written history to present a united Peter and Paul and advance a single orthodoxy against the Marcionites (Marcion was a 2nd-century heretic who wished to cut Christianity off entirely from the Jews); Baur continues to have enormous influence, but today there is less interest in determining the historical accuracy of Acts (although this has never died out) than in understanding the author's theological program.

[21] The author assumes an educated Greek-speaking audience, but directs his attention to specifically Christian concerns rather than to the Greco-Roman world at large.

The second key element is the roles of Peter and Paul, the first representing the Jewish Christian church, the second the mission to the Gentiles.

The apostles and other followers of Jesus meet and elect Matthias to replace Judas Iscariot as a member of The Twelve.

Stephen's death marks a major turning point: the Jews have rejected the message, and henceforth it will be taken to the Gentiles.

The Gentile church is established in Antioch (north-western Syria, the third-largest city of the empire), and here Christ's followers are first called Christians.

Paul spends the next few years traveling through western Asia Minor and the Aegean, preaching, converting, and founding new churches.

[40] Luke's theology is expressed primarily through his overarching plot, the way scenes, themes and characters combine to construct his specific worldview.

[43] For Luke, the Holy Spirit is the driving force behind the spread of the Christian message, and he places more emphasis on it than do any of the other evangelists.

The Spirit is "poured out" at Pentecost on the first Samaritan and Gentile believers and on disciples who had been baptised only by John the Baptist, each time as a sign of God's approval.

[44] One issue debated by scholars is Luke's political vision regarding the relationship between the early church and the Roman Empire.

For example, the gospel seems to place the Ascension on Easter Sunday, shortly after the Resurrection, while Acts 1 puts it forty days later.

While not seriously questioning the single authorship of Luke–Acts, these variations suggest a complex literary structure that balances thematic continuity with narrative development across two volumes.

[49] Literary studies have explored how Luke sets the stage in his gospel for key themes that recur and develop throughout Acts, including the offer to and rejection of the Messianic kingdom by Israel, and God's sovereign establishment of the church for both Jews and Gentiles.

But details of these same incidents are frequently contradictory: for example, according to Paul it was a pagan king who was trying to arrest him in Damascus, but according to Luke it was the Jews (2 Corinthians 11:33 and Acts 9:24).