Book of Common Prayer (1979)

The first such production was the 1549 Book of Common Prayer, traditionally considered to be work of Thomas Cranmer, which replaced both the missals and breviaries of Catholic usage.

[5] Among these liturgies were the Communion service and canonical hours of Matins and Evensong, with the addition of the Ordinal containing the form for the consecration of bishops, priests, and deacons in 1550.

[6] Under Edward VI, the 1552 Book of Common Prayer incorporated more radically Protestant reforms,[7]: 11 a process that continued with 1559 edition approved under Elizabeth I.

The 1559 edition was for some time the second-most diffuse book in England, behind only the Bible, through an act of Parliament that mandated its presence in each parish church across the country.

[10][11] A further revision with a greater departure from the English 1662 edition was approved for regular usage by the newly established Episcopal Church in 1789.

Notably, the Eucharistic prayers of this approved edition included a similar Epiclesis invoking the Holy Spirit as that present in Eastern Christian rituals and the Episcopal Church of Scotland's liturgy.

[7]: 12 Proposals to remove the Nicene and Athanasian Creeds faced successful objections from both a caucus of High Church Virginians and English bishops who had been consulted on the prayer book's production.

[21] The revision also sought to eschew perceived "medieval" and "pagan" qualities, such as reference to God's anger, as well as altering prayers to remove "extreme Calvinism.

"[18][17]: 64 The then-Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer John Wallace Suter lauded the 1928 for its "new flexibility" and considered it as a text to be used continuously through the life of both the laity and clergy.

[17]: 65 The Second Vatican Council and the Catholic Church's adoption of the Mass in the vernacular as standard during the process of aggiornamento represented a significant high point in the influence of the Liturgical Movement, a loose effort to improve Christian worship practices across denominational lines.

[23]: 194 Even prior to these developments, early proponents of the Liturgical Movement within Episcopal Church had laid the groundwork for revision.

Parsons and Jones, after publishing the influential history The American Prayer Book in 1937, served on the Episcopal Church's Standing Liturgical Commission.

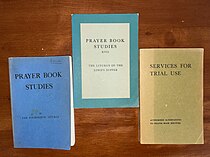

A broader revision was approved at the 1970 General Convention, including a new lectionary and forms for the Daily Office and ordinations, as the Services for Trial Use–known as the "Green Book" for its cover.

[31]: 551–552 The 1976 General Convention approved the usage of a proposed new revision of the Book of Common Prayer by a wide margin.

[35] The Proposed Book of Common Prayer was adopted by the 1979 General Convention in Denver as the official liturgy of the Episcopal Church.

[13]: 63 In 2000, the General Convention passed a resolution apologizing to those who "were offended or alienated by inappropriate or uncharitable behavior during the time of transition to the 1979 Book of Common Prayer."

[15] The 1979 edition of the Book of Common Prayer was intended to contain all the regular public liturgies used within the Episcopal Church, with only limited additional variety permitted by specific exemptions.

The Daily Office utilizes a division of the Psalms in which all 150 are read each month during complete recitation, keeping with Cranmerite practices initiated in the 1549 prayer book.

[7]: 65 The 1979 prayer book introduced two additional liturgies to Episcopal Daily Office: An Order of Worship for the Evening (also known by the Latin name lucernarium) and Compline.

"[15]: 506 The 1979 prayer book's rubrics, drawing from early Christian practices, encourage the baptismal liturgy to be performed alongside Holy Communion on major feasts so that it might be a more public event.

[3]: 7 Many traditionalists, both Anglo-Catholics and evangelicals, felt alienated by the theological and ritual changes made in the 1979 prayer book, and resisted or looked elsewhere for models of liturgy.

[60] Some Continuing Anglican denominations founded after the introduction of the 1979 prayer book have cited it, alongside the ordination of women, as a factor in rejecting the Episcopal Church.

[61][62] In one case, an Antiochian Western Rite Vicariate parish was created from an Episcopal congregation that had rejected the 1979 prayer book.

It also suggested that the Task Force take into consideration new technological means of disseminating the prayer book and to conduct its business in the major languages of The Episcopal Church: English, Spanish, French, and Haitian Creole.

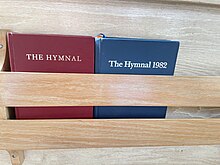

[75] However, the introduction of the two-rite system into the primary liturgies necessitated an even greater expansion in the variety of the hymn selection available.

[76] Canon 24, Section I of the Episcopal Church–included in the front of each copy of The Hymnal 1982–states that it is "the duty of every Minister to see that music is used as an offering to the glory of God."

Among the further aims of the 1982 hymnal were to improve ecumenical relations and "restore music which had lost some of its melodic, rhythmic, or harmonic vitality through prior revision.

It followed the 1991 and 1996 editions of Supplemental Liturgical Materials, and was intended as a further expansion on the texts made available for discretionary usage within those previous publications.