Book of Kells

The Book of Kells (Latin: Codex Cenannensis; Irish: Leabhar Cheanannais; Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS A. I.

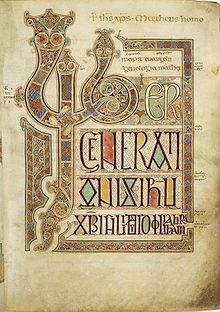

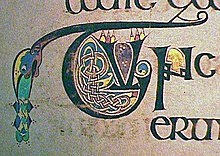

Figures of humans, animals and mythical beasts, together with Celtic knots and interlacing patterns in vibrant colours, enliven the manuscript's pages.

The leaves are high-quality calf vellum; the unprecedentedly elaborate ornamentation that covers them includes ten full-page illustrations and text pages that are vibrant with decorated initials and interlinear miniatures, marking the furthest extension of the anti-classical and energetic qualities of Insular art.

The proposed dating in the 9th century coincides with Viking raids on Lindisfarne and Iona, which began c. 793-794 and eventually dispersed the monks and their holy relics into Ireland and Scotland.

Finally, it may have been the product of Dunkeld or another monastery in Pictish Scotland, though there is no actual evidence for this theory, especially considering the absence of any surviving manuscript from Pictland.

[17] Although the question of the exact location of the book's production will probably never be answered conclusively, the first theory, that it was begun at Iona and continued at Kells, is widely accepted.

Cassiodorus in particular advocated both practices, having founded the monastery Vivarium in the sixth century and having written Institutiones, a work which describes and recommends several texts—both religious and secular—for study by monks.

Later, the Carolingian period introduced the innovation of copying texts onto vellum, a material much more durable than the papyrus to which many ancient writings had been committed.

The description certainly matches Kells: This book contains the harmony of the Four Evangelists according to Jerome, where for almost every page there are different designs... and other forms almost infinite... Fine craftsmanship is all about you, but you might not notice it.

The association with St. Columba, who died the same year Augustine brought Christianity and literacy to Canterbury from Rome, was used to demonstrate Ireland's cultural primacy, seemingly providing "irrefutable precedence in the debate on the relative authority of the Irish and Roman churches".

[34] The manuscript is in remarkably good condition considering its age, though many pages have suffered some damage to the delicate artwork due to rubbing.

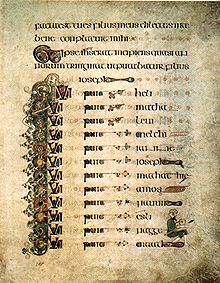

Second and more importantly, the corresponding chapter numbers were never inserted into the margins of the text, making it impossible to find the sections to which the canon tables refer.

The reason for the omission remains unclear: the scribe may have planned to add the references upon the manuscript's completion, or he may have deliberately left them out so as not to spoil the appearance of pages.

This anomalous order mirrors that found in the Book of Durrow, although in the latter instance, the misplaced sections appear at the very end of the manuscript rather than as part of a continuous preliminary.

"[52] The lavishly decorated opening page of the Gospel according to John had been deciphered by George Bain as: "In principio erat verbum verum"[53] (In the beginning was the True Word).

[54] A blank page at the end of Luke (folio 289v) contains a poem complaining of taxation upon church land, dated to the 14th or 15th century.

In the early 17th century one Richardus Whit recorded several recent events on the same page in "clumsy" Latin, including a famine in 1586, the accession of James I, and plague in Ireland during 1604.

The signature of Thomas Ridgeway, 17th century Treasurer of Ireland, is extant on folio 31v, and the 1853 monogram of John O. Westwood, author of an early modern account of the book, is found on 339r.

The kinetic energy of their contours escapes into freely drawn appendices, a spiral line which in turn generates new curvilinear motifs...".

[72][73] The miniature of the Virgin and Child faces the first page of the text, which begins the Breves causae of Matthew with the phrase Nativitas Christi in Bethlem (the birth of Christ in Bethlehem).

According to earlier accounts given by Isidore of Seville and Augustine in The City of God, the peacocks' flesh does not putrefy; the animals therefore became associated with Christ via the Resurrection.

The blank verso of folio 33 faces the single most lavish miniature of the early medieval period, the Book of Kells Chi Rho monogram, which serves as incipit for the narrative of the life of Christ.

In the Book of Kells, this second beginning was given a decorative programme equal to those prefacing the Gospels, its Chi Rho monogram having grown to consume the entire page.

A few pages later (folio 124r) is found a very similar decoration of the phrase "Tunc crucifixerant Xpi cum eo duos latrones" (Matthew 27:38[85]), Christ's crucifixion together with two thieves.

It is significant that the Chronicles of Ulster state the book was stolen from the sacristy, where the vessels and other accoutrements of the Mass were stored, rather than from the monastic library.

The majority of the pages were reproduced in black-and-white photographs, but the edition also featured forty-eight colour reproductions, including all the full-page decorations.

Under licence from the Board of Trinity College Dublin, Thames and Hudson produced a partial facsimile edition in 1974, which included a scholarly treatment of the work by Françoise Henry.

By 1986, Faksimile-Verlag had developed a process that used gentle suction to straighten a page so that it could be photographed without touching it and so won permission to publish a new facsimile.

[3][101] The Ireland in which the Book of Kells was crafted and manufactured, writes Christopher de Hamel, "was clearly no primitive backwater but a civilization which could now read Latin, although never occupied by the Romans, and which was somehow familiar with texts and artistic designs which have unambiguous parallels in the Coptic and Greek churches, such as carpet pages and Canon tables.

Although the Book of Kells itself is as uniquely Irish as anything imaginable, it is a Mediterranean text and the pigments used in making it include orpiment, a yellow made from arsenic sulphide, exported from Italy, where it is found in volcanoes.