Anglo-Saxon art

The important artistic centres, in so far as these can be established, were concentrated in the extremities of England, in Northumbria, especially in the early period, and Wessex and Kent near the south coast.

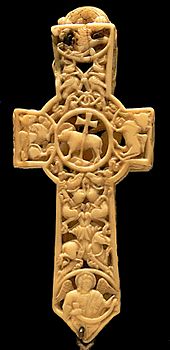

Anglo-Saxon artists also worked in fresco, stone, ivory and whalebone (notably the Franks Casket), metalwork (for example the Fuller brooch), glass and enamel, many examples of which have been recovered through archaeological excavation and some of which have simply been preserved over the centuries, especially in churches on the Continent, as the Vikings, Normans and Reformation iconoclasm between them left virtually nothing in England except for books and archaeological finds.

The Kingdom of Northumbria in the far north of England was the crucible of Insular style in Britain, at centres such as Lindisfarne, founded c. 635 as an offshoot of the Irish monastery on Iona, and Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey (674) which looked to the continent.

[4] King Alfred (r. 871–899) held the Vikings back to a line running diagonally across the middle of England, above which they settled in the Danelaw, and were gradually integrated into what was now a unified Anglo-Saxon kingdom.

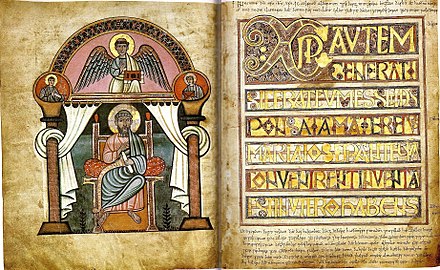

In the Lindisfarne Gospels, of around 700–715, there are carpet pages and Insular initials of unprecedented complexity and sophistication, but the evangelist portraits, clearly following Italian models, greatly simplify them, misunderstand some details of the setting, and give them a border with interlace corners.

Yet the same artist almost certainly produced both pages, and is very confident in both styles; the evangelist portrait of John includes roundels with Celtic spiral decoration probably drawn from the enamelled escutcheons of hanging bowls.

[13] Manuscripts from the Winchester School or style only survive from about the 930s onwards; this coincided with a wave of revival and reform within English monasticism, encouraged by King Æthelstan (r. 924/5-939) and his successors.

[14] Miniatures added in England to the continental Aethelstan Psalter begin to show Anglo-Saxon liveliness in figure drawing in compositions derived from Carolingian and Byzantine models, and over the following decades the distinctive Winchester style with agitated draperies and elaborate acanthus borders develops.

Despite a considerable number of other finds, the discovery of the ship-burial at Sutton Hoo, probably interred in the 620s, transformed the history of Anglo-Saxon art, showing a level of sophistication and quality that was wholly unexpected at this date.

The most famous finds are the helmet and matching suite of purse-lid, belt and other fittings of the king buried there, which made clear the source in Anglo-Saxon art, previously much disputed, of many elements of the style of Insular manuscripts.

Wall-paintings, which seem to have sometimes contained gold, were also apparently often made by manuscript illuminators, and Goscelin's description of his talents therefore suggests an artist skilled in all the main Anglo-Saxon media for figurative art – of which being a goldsmith was then regarded as the most prestigious branch.

[25] Sections of decorated elements from some large looted works such as reliquaries were sawn up by Viking raiders and taken home to their wives to wear as jewellery, and a number of these survive in Scandinavian museums.

Especially in the 9th century, Anglo-Saxon styles, sometimes derived from manuscripts rather than metal examples, are found in a great number of smaller pieces of jewellery and other small fittings from across northern Europe.

The most ornate of earlier ones are colourful and complicated with inlays and filigrees, but the 9th century Pentney Hoard, discovered in 1978, contained six splendid brooches in flat silver openwork in the "Trewhiddle style".

In these small but fully formed animals, of no recognisable species, contort themselves in foliage and tendrils that interlace, but without the emphatic geometry of the earlier "ribbon" style.

Objects from the Royal Anglo-Saxon tomb in Prittlewell in Essex, dating from the late 6th century and discovered in 2003, were put on display in Southend Central Museum in 2019.

The earliest Anglo-Saxon coin type, the silver sceat, forced craftsmen, no doubt asked to copy Roman and contemporary continental styles, to work outside their traditional forms and conventions in respect of the heads on the obverse, with results that are varied and often compelling.

Later silver pennies, with largely linear relief heads of kings in profile on the obverse, are more uniform, as representatives of what was a stable and respected currency by contemporary European standards.

[30] A number of complete seax knives have survived with inscriptions and some decoration, and sword fittings and other military pieces are an important form of jewellery.

A treatise on social status needed to say that mere ownership of a gilded sword did not make a man a ceorle, the lowest rank of free men.

Sculpture in wood was very likely more common, but almost the only significant large survival is St Cuthbert's coffin in Durham Cathedral, probably made in 698, with numerous linear images carved or incised in a technique that is a sort of large-scale engraving.

[38] In the early stages the successive styles of Norse art appear in England, but gradually as political and cultural ties weakened the Anglo-Scandinavians fail to keep up with trends in the homeland.

[39] A uniquely Anglo-Scandinavian form is the hogback, low grave-marker shaped like a long house with a pitched roof, and sometimes muzzled bears clutching on to each end.

It contains a unique mixture of pagan, historical and Christian scenes, evidently attempting to cover a general history of the world, and inscriptions in runes in both Latin and Old English.

[50] The earliest group of survivals, now re-arranged and with the precious metal thread mostly picked out, are bands or borders from vestments, incorporating pearls and glass beads, with various types of scroll and animal decoration.

[51] A further style of textile is a vestment illustrated in a miniature portrait of Saint Aethelwold in his Benedictional (see above), which shows the edge of what appears to be a huge acanthus "flower" (a term used in several documentary records) covering the wearer's back and shoulders.

Vessel and bead production probably continued, at a much lower level, from the Romano-British industry, but Bede records that Benedict Biscop brought glass-makers from Gaul for window glass at his monasteries.

Enamel was used, most famously in the Alfred Jewel, where the image sits under carved rock crystal, both materials are extremely rare in surviving Anglo-Saxon work.

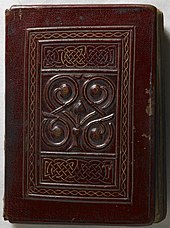

The unique decorated leather cover of the small Northumbrian St Cuthbert Gospel, the oldest Western bookbinding to survive unaltered, can be dated to 698 or shortly before.

[58] Several images in the Old English Hexateuch are believed to be the earliest surviving visual representations of the Horns of Moses, an iconographic convention which grew over the rest of the Middle Ages.