Book of hours

[2] The use of a book of hours was especially popular in the Middle Ages, and as a result, they are the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript.

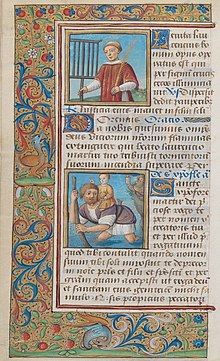

A typical book of hours contains the Calendar of Church feasts, extracts from the Four Gospels, the Mass readings for major feasts, the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the fifteen Psalms of Degrees, the seven Penitential Psalms, a Litany of Saints, an Office for the Dead and the Hours of the Cross.

The Marian prayers Obsecro te ("I beseech thee") and O Intemerata ("O undefiled one") were frequently added, as were devotions for use at Mass, and meditations on the Passion of Christ, among other optional texts.

By the 12th century this had developed into the breviary, with weekly cycles of psalms, prayers, hymns, antiphons, and readings which changed with the liturgical season.

Such additions might amount to no more than the insertion of some regional or personal patron saint in the standardized calendar, but they often include devotional material added by the owner.

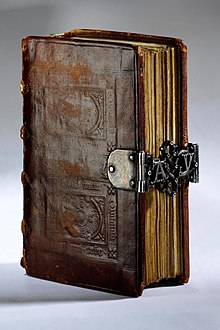

[8] By at least the 15th century, the Netherlands and Paris workshops were producing books of hours for stock or distribution, rather than waiting for individual commissions.

The new style can be seen in the books produced by the Oxford illuminator William de Brailes who ran a commercial workshop (he was in minor orders).

The text, augmented by rubrication, gilding, miniatures, and beautiful illuminations, sought to inspire meditation on the mysteries of faith, the sacrifice made by Christ for man, and the horrors of hell, and to especially highlight devotion to the Virgin Mary whose popularity was at a zenith during the 13th century.

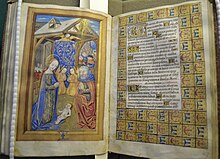

[12] As many books of hours are richly illuminated, they form an important record of life in the 15th and 16th centuries as well as the iconography of medieval Christianity.

Secular scenes of calendar cycles include many of the best known images from books of hours, and played an important role in the early history of landscape painting.

Many have handwritten annotations, personal additions and marginal notes but some new owners also commissioned new craftsmen to include more illustrations or texts.

Flyleaves of some surviving books include notes of household accounting or records of births and deaths, in the manner of later family bibles.

From the late 14th century a number of bibliophile royal figures began to collect luxury illuminated manuscripts for their decorations, a fashion that spread across Europe from the Valois courts of France and the Burgundy, as well as Prague under Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and later Wenceslaus.

By the mid-15th century, a much wider group of nobility and rich businesspeople were able to commission highly decorated, often small, books of hours.

With the arrival of printing, the market contracted sharply, and by 1500 the finest quality books were once again being produced only for royal or very grand collectors.

(Among the plants are the Veronica , Vinca , Viola tricolor , Bellis perennis , and Chelidonium majus . The lower butterfly is Aglais urticae , the top left butterfly is Pieris rapae . The Latin text is a devotion to Saint Christopher ).