Pre-Tridentine Mass

Following the Council of Trent's desire for standardization, Pope Pius V, with his bull Quo primum, made the Roman Missal obligatory throughout the Latin Church, except for those places and congregations whose distinct rites could demonstrate an antiquity of two hundred years or more.

The earliest surviving account of the celebration of the Eucharist or the Mass in Rome is that of Saint Justin Martyr (died c. 165), in chapter 67 of his First Apology:[2] On the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things.

Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons.In chapter 65, Justin Martyr says that the kiss of peace was given before the bread and the wine mixed with water were brought to "the president of the brethren".

[5][6] Before the pontificate of Pope Gregory I (590–604), the Roman Mass rite underwent many changes, including a "complete recasting of the Canon" (a term that in this context means the Anaphora or Eucharistic Prayer).

500-750) has been called "the experimental age of liturgy," with the propers constructed freely: according to historian Yitzhak Hen "each bishop, abbot or priest was free to choose the prayers he found suitable.

Gallican influence is responsible for the introduction into the Roman rite of dramatic and symbolic ceremonies such as the blessing of candles, ashes, palms, and much of the Holy Week ritual.

[12]: Preface Towards the end of the first millennium, organ, previously a secular instrument, was introduced as did more complicated singing of components of the Mass by choirs.

[13] Important liturgies might be preceded, followed or interrupted by elaborate processions with songs, dramatic rituals involving props, and acted plays or tableau, with the laity trained to understand the symbolism.

[27]: 54 The Pre-Tridentine Mass survived post-Trent in some Anglican and Lutheran areas with some local modification from the basic Roman rite until the time when worship switched to the vernacular.

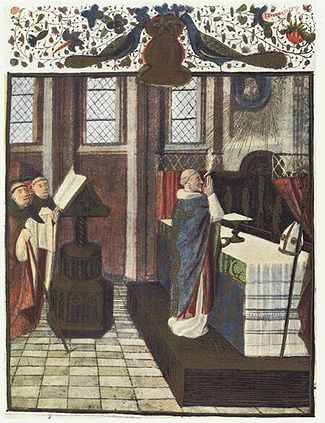

[28] Historian Virginia Reinburg has noted that the medieval eucharistic liturgy as experienced by (French) lay people, and shown in their prayer books, was a distinct experience from that of the clergy and the clerical missal.

[29]: 529 "What the lay prayer books reveal—and missals do not—is the pre-Reformation mass as a ritual drama in which the priests and the congregation had distinct, but equally necessary parts to play.

"[29]: 530 In the Carolingian period, the Mass was increasingly performed as sacred drama, with the people as active participants not passive spectators:[30]: 460 Archbishop Amalarius of Metz (c.830) was accused of imparting "theatrical elements and stage mannerisms" to the Frankish liturgy.

[31] The medieval lay experience was often highly sensory:[32] churches featured chanting and singing, bells, high-tech organs, incense, busy paintings, brilliant robes, rare colours, shiny utensils, clouds of saints and angels, and stained-glass light, not to mention the taste of the host, the splashing of baptism, or even, perhaps, the feel of the silk of the priest's violet stole in absolution.

[…]The laity's mass was less sacrifice and sacrament than a communal rite of greeting, sharing, giving, receiving and making peace.

"[29]: 533 Notable parts of the lay experience of the liturgy (especially the Sunday Mass) included: If any priest says he cannot preach (i.e. give composed or extemporized vernacular sermons), one remedy is: resign; [...] Another remedy, if he does not want that, is: record (i.e., recollect or write out)[49] he in the week the naked text of the Sunday's gospel, that he understands the gross story, and tell it to the people, that is if he understands Latin and does it every week of the year.

Depending on calendar, occasion, participants, region and period, some parts might be augmented or commented on (tropes)[51] or removed or rearranged or varied from standard forms.

Over time, the parts may be grouped or re-named to reflect the contemporary theological or pastoral priorities, but were typically known by the first words of the Latin of the prayer.