Destination-based cash flow tax

It was proposed in the United States by the Republican Party in their 2016 policy paper "A Better Way — Our Vision for a Confident America",[6] which promoted a move to the tax.

Unless it is immediate and as complete as Auerbach anticipates, the increased cost to importers would result in higher consumer prices which would "hit low-income households disproportionately.

"[2] Some economists and policy makers have also expressed concern that other countries could challenge border-adjustment tax with the World Trade Organization[14] or impose retaliatory tariffs;[15] and there is also strong opposition by some US corporate interests.

[14] Over the years, Auerbach has worked with Michael Devereux, who had co-introduced with Stephen R. Bond, the term destination-based corporate tax.

"[7] While in theory, a border-adjustment tax is trade neutral, both The Economist and the Brookings Institution caution that if the exchange rate did not adjust, it would be painful for importers and low-income households.

On June 24, they presented a policy paper, entitled "A Better Way: Our Vision for a Confident America", which promoted a move to "a destination-basis tax system.

"[19] As Ryan defended border-adjustment levy at a press conference on February 17, the Koch brothers-funded Americans for Prosperity (AFP), an influential lobby group, unveiled their plan to fight the taxes.

[18] In President Trump's cabinet, supporters include Steve Bannon, Senior Counselor while Gary Cohn, the former Goldman Sachs investment banker and executive, Director of the National Economic Council is opposed.

[14] Senator Tom Cotton (Arkansas) estimated that the one billion a year that corporations will save in revenue would be paid by working Americans as they purchase T-shirts and baby clothes.

[3] Caroline Freund, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, described how the "Better Way" plan incorporates "border-tax adjustments into business taxes."

[2] In theory, a border-adjustment tax is trade-neutral: the stronger domestic currency would make exports more expensive internationally, lowering demand for exported products while reducing the costs incurred by domestic firms in purchasing goods and services in foreign markets, helping importers.

Thus, the anticipated strengthening of the domestic currency effectively neutralizes the border-adjustment tax, resulting in a trade-neutral outcome.

To offset a border-adjusted tax of 20%—the rate favoured by House Republicans—the greenback would need to rise fully 25%, enough to destabilise emerging markets burdened with dollar-denominated debts.

Consumer prices would rise, fueled by higher import costs, and this would hit low-income households disproportionately.

[29] Border-adjustment taxes would eliminate incentives that drive US corporations to "shift profit overseas and overcharge for purchases from subsidiaries abroad.

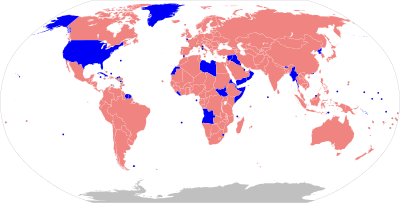

[7] Those who oppose the border-adjustment tax have concerns about the impact on the US dollar exchange rate, which would benefit countries like China and Japan that hold a large portion of the US debt, retaliations by trade partners, legal challenges through the World Trade Organization, and benefits to larger American corporations that export at the cost of smaller and medium-sized domestic companies that import, and therefore their customers, especially middle- and lower-income American consumers.

Consumer prices would rise, fueled by higher import costs, and this would hit low-income households disproportionately.

The DBCFT, however, taxes the entire value of the import but only the above-normal return to capital owners of domestically produced goods.

According to a January 18, 2017 article in Bloomberg View, while it has been asserted that the proposed border-adjustment tax would be compatible with WTO rules, that is controversial.

[7] Critics have argued that a border-adjustment tax may disproportionately and adversely impact domestic companies that import products or parts, such as those in the retail, clothing, shoes, automotive, consumer electronics, and oil industries while favoring large, domestic exporters, such as those in the aerospace, defense or technology sectors.

Industrial multinational companies who are exporters, such as Dow Chemical Co., Pfizer, General Electric and Boeing, support the levy.

[14][17][18] Along with Koch Industries, those who oppose it include oil refiners, car dealers, represented by American International Automobile Dealers Association including Toyota Motor Corp, toy manufacturers, retailers[30] such as Target Corporation, Gap Inc., Nike Inc., McCormick & Co., and Walmart, which depend on "importing foreign-made goods.