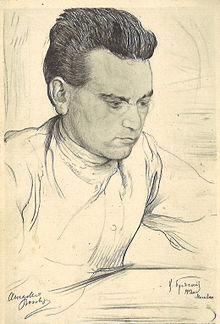

Amadeo Bordiga

Victor Serge, who witnessed the 2nd Comintern Congress, remembered Bordiga as "exuberant and energetic, features blunt, hair thick, black and bristly, a man quivering under his encumbrance of ideas, experiences and dark forecasts.

"[3] When the PSI held its congress at Livorno in January 1921, representatives sent by Comintern, all insisted that the party must expel its reformist wing led by Filippo Turati but were divided over whether to continue to work with Giacinto Menotti Serrati, who advised delaying the split.

Bordiga advocated an immediate break with both Serrati and Turati, and hence with the majority of the PSI, and prevailed against the opposition of the leading Comintern representative Paul Levi but also with the backing of others, including Matyas Rakosi, the future Stalinist dictator of Hungary.

[5] For Bordiga, the party was the social brain of the proletariat whose task was not to seek majority support but to concentrate on working for an armed insurrection in the course of which it would seize power and then use it to abolish capitalism and impose a communist society by force.

[citation needed] This position was accepted by the majority of the members of the PCdI but was to bring them into conflict with the Comintern when in 1921 the latter adopted a new tactic, i.e. that of the united front with reformist organisations to fight for social reforms and even to form a workers' government.

When Bordiga was arrested in February 1923 on a trumped-up charge by the new government of Benito Mussolini, he had to give up his post as a member of the Central Committee of the PCdI.

At the Fifth Congress of Comintern in Moscow held in June–July 1924, Bordiga was the sole voice of the ultra-left who opposed any cooperation with socialist parties in favour of a "united front from below, not from above", which received support except within the Italian delegation.

"[6] Also in 1924, the Italian communist left lost control of the PCdI to a pro-Moscow group whose leader Gramsci became the party's General Secretary in June.

[citation needed] In December 1926, Bordiga was again arrested by Mussolini and sent to prison in Ustica, an Italian island in the Tyrrhenian Sea, where he met with Gramsci and they renewed their friendship and worked alongside each other despite their political differences.

[8] Following his release, Bordiga did not resume his activities in the PCdI and was in fact expelled in March 1930, accused of having "supported, defended and endorsed the positions of the Trotskyist opposition" and been organisationally disruptive.

According to Alliotta, Bordiga believed Nazi Germany was weakening the "English giant", which to him was "the greatest exponent of capitalism", and thus the defeat of Britain would bring about revolutionary conditions in Europe.

[9] Other sources cast doubt on the analysis that Bordiga supported Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy, citing ‘contradictory’ testimony on the issue.

When this grouping was dissolved into the Internationalist Communist Party (PCInt), Bordiga did not initially join; despite this, he contributed anonymously to its press, primarily Battaglia Comunista and Prometeo, in keeping with his conviction that revolutionary work was collective in nature and his opposition to any form of even incipient personality cult.

[13] In particular, he emphasized how much of the national agrarian produce came from small privately owned plots (writing in 1950) and predicted the rates at which the Soviet Union would start importing wheat after Imperial Russia had been such a large exporter from the 1880s to 1914.

He felt that the Marxist–Leninist states that came into existence after 1945 were extending the bourgeois nature of prior revolutions that degenerated as all had in common a policy of expropriation and agrarian and productive development, which he considered negations of previous conditions and not the genuine construction of socialism.

As such, Bordiga opposed the idea of revolutionary theory being the product of a democratic process of pluralist views, believing that the Marxist perspective has the merit of underscoring the fact that, like all social formations, communism is above all about the expression of programmatic content.

This enforces the fact that, for Marxists, communism is not an ideal to be achieved but a real movement born from the old society with a set of programmatic tasks.

Bordiga had a completely different view of the party from the Comintern,[17] which was adapting to the revolutionary ebb that was announced in 1921 by the Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement, the Kronstadt rebellion, the implementation of the New Economic Policy, the banning of factions, and the defeat of the March Action in Germany.

The role of the party in the period of ebb was to preserve the program and to carry on the propaganda work possible until the next turn of the tide, not to dilute it while chasing ephemeral popularity.

Bordiga's analysis provided a way of seeing a fundamental degeneration in the world communist movement in 1921 (instead of in 1927 with the defeat of Trotsky) without simply calling for more democracy.

Sticking to Marx's concept of communism, for Bordiga both stages of socialist or communist society—with stages referring to historical materialism—were characterised by the absence of money, capital, the market, and so on, the difference between them being that earlier in the first stage rationing would be done in a way in which "a given amount of labor in one form is exchanged for an equal amount of labor in another form",[18] with deductions being made from said labor to fund public projects, and difference in interests between the rural and urban proletariat would exist, whilst in communism "bourgeoisie law" would be no more, hence the equal standard applied to all peoples no longer would apply, and the alienated man "will not aim to win back his person" but rather become a new "Social Man".