Name of Canada

While a variety of theories have been postulated for the name of Canada, its origin is now accepted as coming from the St. Lawrence Iroquoian word kanata, meaning 'village' or 'settlement'.

[1] In 1535, indigenous inhabitants of the present-day Quebec City region used the word to direct French explorer Jacques Cartier to the village of Stadacona.

[11] The name Canada is now generally accepted as originating from the St. Lawrence Iroquoian word kanata ([kana:taʔ]), meaning 'village' or 'settlement'.

[12][14] This explanation is historically documented in Jacques Cartier's Bref récit et succincte narration de la navigation faite en MDXXXV et MDXXXVI.

[15] A widespread perception in Canadian folklore is that Cartier misunderstood the term "Canada" as the existing proper name of the Iroquois people's entire territory rather than the generic class noun for a town or village.

[20][21] The earliest iterations of the Spanish "nothing here" theory stated that the explorers made the declaration upon visiting the Bay of Chaleur,[22] while later versions left out any identifying geographic detail.

Neither region is located anywhere near Iroquoian territory, and the name Canada does not appear on any Spanish or Portuguese maps of the North American coast that predate Cartier's visit.

In most versions of the Iberian origin theory, the Spanish or Portuguese passed their name on to the Iroquois, who rapidly adopted it in place of their own prior word for a village;[21] however, no historical evidence for any such Iberian-Iroquoian interaction has ever actually been found.

[21] Elliott's "valley" theory, conversely, was that the Spanish gave their name for the area directly to Jacques Cartier, who then entirely ignored or passed over the virtually identical Iroquoian word.

[12] Additional theories have attributed the name "Canada" to: a word in an unspecified indigenous language for 'mouth of the country' in reference to the Gulf of St. Lawrence;[12] a Cree word for 'neat or clean';[26] a claimed Innu war cry of "kan-na-dun, Kunatun";[24] a shared Cree and Innu word, p'konata, which purportedly meant 'without a plan' or 'I don't know';[27] a short-lived French colony purportedly established by a settler whose surname was Cane;[12] Jacques Cartier's description elsewhere in his writings of Labrador as "the land God gave to Cain;" or, to a claim that the early French habitants demanded a "can a day" of spruce beer from the local intendant[12] (a claim easily debunked by the fact that the habitants would have been speaking French, not English).

In their 1983 book The Anglo Guide to Survival in Québec, humourists Josh Freed and Jon Kalina tied the Iberian origin theory to the phrase nada mas caca ('nothing but shit').

[37] On these names, the statesman Thomas D'Arcy McGee commented, "Now I would ask any honourable member of the House how he would feel if he woke up some fine morning and found himself, instead of a Canadian, a Tuponian or a Hochelegander?".

[46] The governor general at the time, The 4th Viscount Monck, supported the move to designate Canada a kingdom;[47] however, officials at the Colonial Office in London opposed this potentially "premature" and "pretentious" reference for a new country.

They were also wary of antagonizing the United States, which had emerged from its Civil War as a formidable military power with unsettled grievances because British interests had sold ships to the Confederacy despite a blockade, and thus opposed the use of terms such as kingdom or empire to describe the new country.

It continued to apply as a generic term for the major colonial possessions of the British Empire until well into the 20th century;[51] although Tilley and the other Fathers of Confederation broadened the meaning of the word dominion to a "virtual synonym for sovereign state".

In a letter to Lord Knutsford on the topic of the loss of the use of the word kingdom, Macdonald said: A great opportunity was lost in 1867 when the Dominion was formed out of the several provinces…The declaration of all the B.N.A.

provinces that they desired as one dominion to remain a portion of the Empire, showed what wise government and generous treatment would do, and should have been marked as an epoch in the history of England.

His ill-omened resignation was followed by the appointment of the late Duke of Buckingham, who had as his adviser the then Governor General, Lord Monck - both good men, certainly, but quite unable, from the constitution of their minds, to rise to the occasion.

[54][55]He added as a postscript that it was adopted on the suggestion of British colonial ministers to avoid offending republican sensibilities in the United States: P.S.

I mentioned this incident in our history to Lord Beaconsfield at Hughenden in 1879, who said, 'I was not aware of the circumstance, but it is so like Derby, a very good fellow, but who lives in a region of perpetual funk.

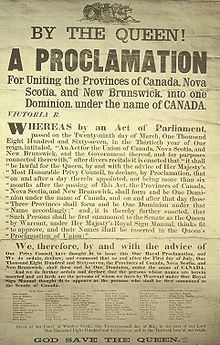

In the Constitution of Canada, namely the Constitution Act, 1867 (British North America Acts), the preamble of the act indicates: Whereas the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick have expressed their Desire to be federally united into One Dominion under the Crown of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom....[57]Moreover, section 2 indicates that the provinces: ... shall form and be One Dominion under the Name of Canada; and on and after that Day those Three Provinces shall form and be One Dominion under that Name accordingly.

As the country acquired political authority and autonomy from the United Kingdom, the federal government began using simply Canada on state documents.

Under Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent, compromises were reached that quietly, and without legislation, "Dominion" would be retired in official names and statements, usually replaced by "federal".