Boroughitis

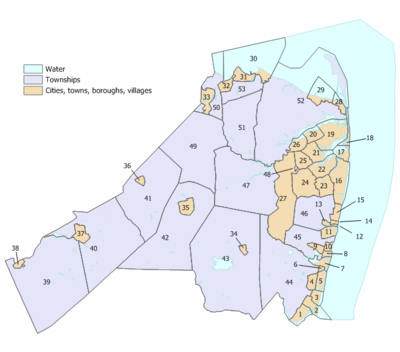

Attempts by the New Jersey Legislature to reform local government and school systems led to the breakup of most of Bergen County's townships into small boroughs, which still balkanize the state's political map.

This occurred following the development of commuter suburbs in New Jersey, residents of which wanted more government services, whereas the long-time rural population feared the increases in taxation that would result.

Political disputes arose between the growing number of commuters, who wanted more government services for the new developments near railroad lines, and long-time residents such as farmers, who understood this to come with higher taxes.

A previously little-used law permitted small segments of existing townships to vote by referendum to form independent boroughs.

In late 1893, Republicans, backed by commuters, captured control of the legislature; the following year, they passed legislation allowing boroughs that were formed from parts of two or more townships to elect a representative to the county Board of Chosen Freeholders.

Municipalities continued to be created by the legislature into the 20th century, and although there have been efforts at consolidation in recent years to lower the high cost of government, they have not been particularly effective.

Township meetings occurred each February; the citizens would discuss concerns, voluntarily seek solutions, and collectively appoint agents to carry out their will.

[3] Even before the Civil War, the Brick Church station, in Orange, Essex County, about 15 miles (24 km) from New York City, became the center of the nation's first commuter suburb.

[4] New Jersey's townships acquired a new type of population, consisting of commuters, who formed communities near railroad stations, and who wanted good streets and roads, better funded schools, and a larger stake in the government.

They were fiercely opposed on each issue by the existing rural, agricultural population, who understood that their taxes would need to be raised in order to pay for the services that they did not want.

This referendum could take place on petition of the owners of 10 percent of the land, as measured by value, in the area in question, and 10 days' notice of the vote was required.

"[3] Legal disputes about control of the New Jersey Senate and the Republican desire to undo many Democratic policies occupied the legislature in the early part of its 1894 session.

[13] Nevertheless, interest groups such as local landowners pushed the legislature for permissive policies on municipal incorporation, hoping to gain power in the new governments.

The Hackensack Republican reported on March 1, "the chief reason why Delford [later Oradell], Westwood, Hillsdale and Park Ridge want to become boroughs is that they may avoid what is feared will be heavy macadam tax".

In April, the Republican majority in Trenton let it be known they were working on a bill to solve Delford's problem by allowing boroughs to be formed from portions of two or more townships, and this became the Act of May 9, 1894.

[19] Partisans saw the political possibilities of the 1894 law, and contested control of the Bergen County government through the formation of boroughs that would elect freeholders of their party.

[30] In September 1894, state Senator Henry D. Winton warned that the legislature at its next session was likely to amend if not gut the Borough Act because of the craze in Bergen County.

Nine new members had been added to the Board of Chosen Freeholders from the previous sixteen, Winton noted, with a proportionate increase in the cost of government, which would be further inflated by the multiplicity of boroughs.

The signal that the law might change did not slow the incorporations: Wood-Ridge, Carlstadt, Edgewater, Old Tappan and other boroughs trace their geneses to late 1894.

[26] There were some fistfights and hard feelings over the borough formations, and Russell Jones, whose house was on the newly drawn line between Teaneck and Bogota, saw it burn down as firefighters argued about who had jurisdiction.

That month, Bergen County's school superintendent, John Terhune, wrote a report to Trenton, decrying that the law allowed borough petitioners to set the proposed lines to exclude opponents of incorporation, "The idea of allowing a bare majority the power to accept or reject a few that have dared to oppose the new fad, and for this simple expression of their rights to cut them from all school facilities is radically wrong and gross injustice.

[33] The rush was also slowed by the legislature deciding that no borough created thereafter could maintain a separate school system unless there were at least 400 children living within its limits.

[34] The following year, the legislature undertook a thorough revision of the laws relating to boroughs, and forbade incorporations, dissolutions, or boundary changes without its leave.

[45] He discussed the long-term effect of the boroughitis craze: The ultimate cost to the state's taxpayers ... directly attributable to the Republican reforms of 1894, is incalculable.