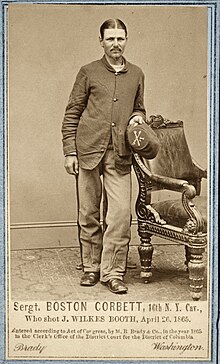

Boston Corbett

Sergeant Thomas H. "Boston" Corbett (January 29, 1832 – disappeared c. May 26, 1888) was an English-born American soldier and milliner who killed John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of President Abraham Lincoln on April 26, 1865.

As a milliner, Corbett was regularly exposed to the fumes of mercury(II) nitrate, then used in the treatment of fur to produce felt used on hats.

Corbett had a hard time finding and keeping work in Richmond, Virginia, in large part because of his vociferous opposition to slavery.

[1][5] After a night of heavy drinking, he was confronted by a street preacher whose message persuaded him to join the Methodist Episcopal Church.

Corbett reportedly encountered some evangelical temperance Christians and was detained by them until he sobered up, undergoing a religious epiphany in the process.

He was reported to be a proficient milliner but was known to proselytize frequently and stop work to pray and sing for co-workers who used profanity in his presence.

[10] He regularly attended meetings at the Fulton and Bromfield Street churches where his enthusiastic behavior earned him the nickname "The Glory to God man".

[3] In an attempt to imitate Jesus, Corbett began to wear his hair very long (he was forced to cut it upon enlisting in the Union Army).

[13] Corbett routinely gathered up drunken sinners from the New York streets and took them to his room, where he would sober them up and feed them, restoring their health and also trying to help them find work.

"[14] On April 19, 1861, early in the American Civil War, Corbett, who was anti-slavery,[15] enlisted as a private in Company I of the Union Army's 12th New York State Militia.

He always carried a Bible with him and read passages aloud from it regularly, held unauthorized prayer meetings, and argued with his superior officers.

"[21] Corbett, among others, led prayer meetings and patriotic rallies to boost morale, according to John McElroy's eyewitness account in his 1879 memoir Andersonville.

[22] After five months, Corbett was released in a prisoner exchange in November 1864 and was admitted to a military hospital in Annapolis, Maryland where he was treated for scurvy, malnutrition and exposure.

Corbett's regiment had barely left the Capitol after the funeral parade when orders caught up with Canadian-born Lt. Edward P. Doherty to pursue a lead about Booth.

[25] On April 26, the regiment surrounded Booth and one of his accomplices, David Herold, in a tobacco barn on the Virginia farm of Richard Garrett.

Colonel Everton Conger came past Corbett, igniting clumps of hay and slipped them in the cracks in the wall, hoping to burn Booth out.

Assessing his condition, Corbett and others felt a cosmic justice in that Booth's entry wound was in the same spot he shot Lincoln.

Initial statements by Doherty and others made no mention of Corbett having violated any orders, nor did they suggest that he would face disciplinary action for shooting Booth.

"[41] Author Scott Martelle disputes this, noting "his initial statement, and those by Baker, Conger, and Doherty don't mention Providence...those details came long after the shooting itself, amid the swirl of rumor and conjecture and considerable lobbying over the reward money."

Booth then began gasping for air as his throat continued to swell, and he made a gurgling sound before he died from asphyxia, approximately two to three hours after Corbett shot him.

[44] According to Johnson, Corbett was accompanied by Lt. Doherty to the War Department in Washington, D.C. to meet Secretary Edwin Stanton about Booth's shooting.

As he made his way to Mathew Brady's studio to have his official portrait taken, the crowd followed him, asking for autographs and requesting that he tell them about shooting Booth.

Initial newspaper reporters described him as a simple and humble man devoted, possibly excessively, to his faith; he had eccentricities but also did his duty well.

[53] After his discharge from the army in August 1865, Corbett returned to work as a milliner in Boston and frequently attended the Bromfield Street Church.

When the hatting business in Boston slowed, Corbett moved to Danbury, Connecticut, to continue his work and also "preached in the country round about."

[54] Corbett's inability to hold a job was attributed to his fanatical behavior; he was routinely fired after continuing his habit of stopping work to pray for his co-workers.

[17] He gave lectures about the shooting of Booth accompanied by illustrated lantern slides at Sunday schools, women's groups and tent meetings.

He became fearful that "Booth's Avengers" or organizations like the "Secret Order" were planning to seek revenge upon him and took to carrying a pistol with him at all times.

[49] While attending the Soldiers' Reunion of the Blue and Gray in Caldwell, Ohio, in 1875, Corbett got into an argument with several men over the death of John Wilkes Booth.

[citation needed] Due to his fame as "Lincoln's Avenger", Corbett was appointed assistant doorkeeper of the Kansas House of Representatives in Topeka in January 1887.