John Wilkes Booth

A member of the prominent 19th-century Booth theatrical family from Maryland,[1] he was a noted actor who was also a Confederate sympathizer; denouncing President Lincoln, he lamented the then-recent abolition of slavery in the United States.

[9] Booth's father built Tudor Hall on the Harford County property as the family's summer home in 1851, while also maintaining a winter residence on Exeter Street in Baltimore.

[19] While attending the Milton Boarding School, Booth met a Romani fortune-teller who read his palm and pronounced a grim destiny, telling him that he would have a grand but short life, doomed to die young and "meeting a bad end".

[23] Booth made his stage debut at age 17 on August 14, 1855, in the supporting role of the Earl of Richmond in Richard III at Baltimore's Charles Street Theatre.

[37] Historian Benjamin Platt Thomas wrote that Booth "won celebrity with theater-goers by his romantic personal attraction", and that he was "too impatient for hard study" and his "brilliant talents had failed of full development.

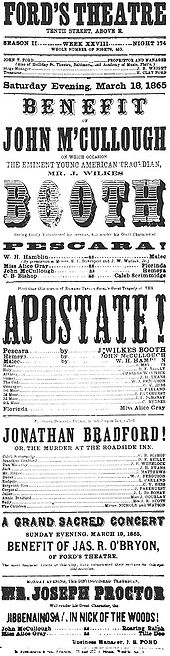

[48] Starting in January 1863, he returned to the Boston Museum for a series of plays, including the role of villain Duke Pescara in The Apostate, that won him acclaim from audiences and critics.

Between September and November 1863, Booth played a hectic schedule in the northeastern United States, appearing in Boston, Providence, Rhode Island, and Hartford, Connecticut.

[56] On November 25, 1864, Booth performed for the only time with his brothers Edwin and Junius in a single engagement production of Julius Caesar at the Winter Garden Theatre in New York.

[43][67] Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860, and the following month Booth drafted a long speech, apparently never delivered, that decried Northern abolitionism and made clear his strong support of the South and the institution of slavery.

According to his sister Asia, Booth confided to her that he also used his position to smuggle the anti-malarial drug quinine, which was crucial to the lives of residents of the Gulf coast, to the South during his travels there, since it was in short supply due to the Northern blockade.

[56][74] As the Civil War went on, Booth increasingly quarreled with his brother Edwin, who declined to make stage appearances in the South and refused to listen to John Wilkes' fiercely partisan denunciations of the North and Lincoln.

Booth had promised his mother at the outbreak of war that he would not enlist as a soldier, but he increasingly chafed at not fighting for the South, writing in a letter to her, "I have begun to deem myself a coward and to despise my own existence.

"[79] He began to formulate plans to kidnap Lincoln from his summer residence at the Old Soldiers Home, three miles (4.8 km) from the White House, and to smuggle him across the Potomac River and into Richmond, Virginia.

[79][80][81][82] Throughout the Civil War, the Confederacy maintained a network of underground operators in southern Maryland, particularly Charles and St. Mary's Counties, smuggling recruits across the Potomac River into Virginia and relaying messages for Confederate agents as far north as Canada.

[85][86] No conclusive proof has linked Booth's kidnapping or assassination plots to a conspiracy involving the leadership of the Confederate government, but historian David Herbert Donald states that "at least at the lower levels of the Southern secret service, the abduction of the Union President was under consideration.

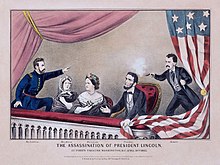

[100] Historian Michael W. Kauffman wrote that, by targeting Lincoln and his two immediate successors to the presidency, Booth seems to have intended to decapitate the Union government and throw it into a state of panic and confusion.

Booth rode into southern Maryland, accompanied by David Herold, having planned his escape route to take advantage of the sparsely settled area's lack of telegraphs and railroads, along with its predominantly Confederate sympathies.

[90][100][114] At midnight, Booth and Herold arrived at Surratt's Tavern on the Brandywine Pike, 9 miles (14 km) from Washington, where they had stored guns and equipment earlier in the year as part of the kidnap plot.

[115] The duo then continued southward, stopping before dawn on April 15 for treatment of Booth's injured leg at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd in St. Catharine, 25 miles (40 km) from Washington.

As the two fugitives hid in the woods nearby, Cox contacted Thomas A. Jones, his foster brother and a Confederate agent in charge of spy operations in the southern Maryland area since 1862.

On April 18, mourners waited seven abreast in a mile-long line outside the White House for the public viewing of the slain president, reposing in his open walnut casket in the black-draped East Room.

[120] Thousands of mourners arriving on special trains jammed Washington for the next day's funeral, sleeping on hotel floors and even resorting to blankets spread outdoors on the Capitol's lawn.

The San Francisco Chronicle editorialized: Booth has simply carried out what...secession politicians and journalists have been for years expressing in words...who have denounced the President as a "tyrant," a "despot," a "usurper," hinted at, and virtually recommended.

[83][132][133] The funeral train slowly made its way westward through seven states, stopping en route at Harrisburg, Philadelphia, Trenton, New York, Albany, Buffalo, Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis during the following days.

"[137] Mourners were viewing Lincoln's remains when the funeral train steamed into Harrisburg at 8:20 pm, while Booth and Herold were provided with a boat and compass by Jones to cross the Potomac at night on April 21.

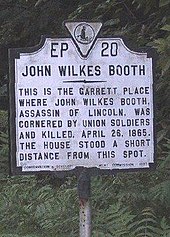

[142][143] The pursuers crossed the Rappahannock River and tracked Booth and Herold to Richard H. Garrett's farm, about 2 miles (3 km) south of Port Royal, Virginia.

[138] The Garretts were unaware of Lincoln's assassination; Booth was introduced to them as "James W. Boyd", a Confederate soldier, they were told, who had been wounded in the Siege of Petersburg and was returning home.

He fell gravely ill and made a deathbed confession that he was the fugitive assassin, but he then recovered and fled, eventually committing suicide in 1903 in Enid, Oklahoma, under the alias "David E.

[174] The Lincoln Conspiracy (1977) contended that there was a government plot to conceal Booth's escape, reviving interest in the story and prompting the display of St. Helen's mummified body in Chicago that year.

[178][179] The application was blocked by Baltimore Circuit Court Judge Joseph H. H. Kaplan, who cited, among other things, "the unreliability of petitioners' less-than-convincing escape/cover-up theory" as a major factor in his decision.