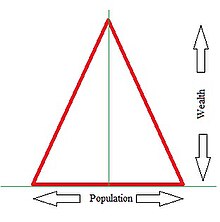

Bottom of the pyramid

[1][2] Management scholar CK Prahalad popularised the idea of this demographic as a profitable consumer base in his 2004 book The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, written alongside Stuart Hart.

[5] Prahalad proposes that businesses, governments, and donor agencies stop thinking of the poor as victims and instead start seeing them as resilient and creative entrepreneurs as well as value-demanding consumers.

[6] He proposes that there are tremendous benefits to multi-national companies who choose to serve these markets in ways responsive to their needs.

Aneel Karnani, also of the Ross School at the University of Michigan, argued in a 2007 paper that there is no fortune at the bottom of the pyramid and that for most multinational companies the market is really very small.

Meanwhile, Hart and his colleague Erik Simanis at Cornell University's Center for Sustainable Global Enterprise advance another approach, one that focuses on the poor as business partners and innovators, rather than just as potential producers or consumers.

[9] Furthermore, Ted London at the William Davidson Institute at the University of Michigan focuses on the poverty alleviation implications of Base of the Pyramid ventures.

This framework, along with other tools and approaches, is outlined in London's Base of the Pyramid Promise and has been implemented by companies, non-profits, and development agencies in Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

Nevertheless, from a normative ethical perspective poverty alleviation is an integral part of sustainable development according to the notion of intragenerational justice (i.e. within the living generation) in the Brundtland Commission's definition.

Ongoing research addresses these aspects and widens the BoP approach also by integrating it into corporate social responsibility thinking.

[citation needed] It has been reported that the gap between the ToP and BoP is widening over time in such a way that only 1% of the world population controls 50% of the wealth today, with the other 99% having access to the remaining 50% only.

[11][12] The standards and benchmarks developed – for example less than $2.5 a day – always tell us about the upper limit of what we call the BoP, and not actually about its base or bottom.

According to Simanis, "Despite achieving healthy penetration rates of 5% to 10% in four test markets, for instance, Procter & Gamble couldn’t generate a competitive return on its Pur water-purification powder after launching the product on a large scale in 2001...DuPont ran into similar problems with a venture piloted from 2006 to 2008 in Andhra Pradesh, India, by its subsidiary Solae, a global manufacturer of soy protein ... Because the high costs of doing business among the very poor demand a high contribution per transaction, companies must embrace the reality that high margins and price points aren't just a top-of-the-pyramid phenomenon; they’re also a necessity for ensuring sustainable businesses at the bottom of the pyramid.

With technology being steadily cheaper and more ubiquitous, it is becoming economically efficient to "lend tiny amounts of money to people with even tinier assets".

Sopan Kumbhar (2013) As Fortune reported on November 15, 2006, since 2005 the SC Johnson Company has been partnering with youth groups in the Kibera slum of Nairobi, Kenya.