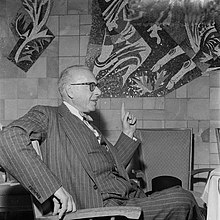

Pierre Boulez

Born in Montbrison, in the Loire department of France, the son of an engineer, Boulez studied at the Conservatoire de Paris with Olivier Messiaen, and privately with Andrée Vaurabourg and René Leibowitz.

Léon (1891–1969), an engineer and technical director of a steel factory, is described by biographers as an authoritarian figure with a strong sense of fairness, and Marcelle (1897–1985) as an outgoing, good-humoured woman, who deferred to her husband's strict Catholic beliefs, while not necessarily sharing them.

The following year he took classes in advanced mathematics at the Cours Sogno in Lyon (a school established by the Lazaristes)[7] with a view to gaining admission to the École Polytechnique in Paris.

[9] In Lyon, Boulez first heard an orchestra, saw his first operas (Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov and Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg)[10] and met the soprano Ninon Vallin, who asked him to play for her.

[20] Although registered at the Conservatoire for the academic year 1945–46, he soon boycotted Simone Plé-Caussade's counterpoint and fugue class, infuriated by what he described as her "lack of imagination", and organised a petition that Messiaen be given a full professorship in composition.

[28] In October 1946, the actor and director Jean-Louis Barrault engaged him to play the ondes for a production of Hamlet for the new company he and his wife, Madeleine Renaud, had formed at the Théâtre Marigny.

The concerts focused initially on three areas: pre-war classics still unfamiliar in Paris (such as Bartók and Webern), works by the new generation (Stockhausen, Nono) and neglected masters from the past (Machaut, Gesualdo)—although the last category fell away in subsequent seasons, in part because of the difficulty of finding musicians with experience of playing early music.

[44] Key events in the Domaine's history included a Webern festival (1955), the European premiere of Stravinsky's Agon (1957) and first performances of Messiaen's Oiseaux exotiques (1955) and Sept haïkaï (1963).

[47] William Glock wrote: "even at a first hearing, though difficult to take in, it was so utterly new in sound, texture and feeling that it seemed to possess a mythical quality like that of Schoenberg's Pierrot lunaire".

[61] He also conducted performances of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde with the Bayreuth company at the Osaka Festival in Japan in 1967, but the lack of adequate rehearsal made it an experience he later said he would rather forget.

[80] There were occasional forays into the classical and romantic repertoire, particularly at the Proms (Beethoven's Missa solemnis in 1972; the Brahms German Requiem in 1973),[82] but for the most part he worked intensively with the orchestra on the music of the twentieth century.

[91] In 1970 Boulez was asked by President Pompidou to return to France and set up an institute specialising in musical research and creation at the arts complex—now known as the Centre Georges Pompidou—which was planned for the Beaubourg district of Paris.

He made his last public appearance on 30 May 2013 at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, discussing Stravinsky with Robert Piencikowski, to mark the centenary of the premiere of The Rite of Spring.

[124] His health prevented him from taking part in the many celebrations held across the world for his 90th birthday in 2015, which included a multi-media exhibition at the Musée de la Musique in Paris, focusing on the inspiration he had drawn from literature and the visual arts.

Of Le Visage nuptial[n 2] Paul Griffiths observes that "Char's five poems speak in hard-edged surrealist imagery of an ecstatic sexual passion", which Boulez reflected in music "on the borders of fevered hysteria".

"[154] Structures, Book I was a turning point for Boulez; from here on he loosened the strictness of total serialism into a more supple, gestural music: "I am trying to rid myself of my thumbprints and taboos", he wrote to Cage.

In later works, such as Cummings ist der Dichter[n 14] (1970, revised 1986)—a chamber cantata for 16 solo voices and small orchestra using a poem by E. E. Cummings—the conductor chooses the order of certain events but there is no freedom for the individual player.

[167] Jonathan Goldman identifies a major aesthetic shift in Boulez's work from the mid-1970s onwards, characterised variously by the presence of thematic writing, a return to vertical harmony and to clarity and legibility of form.

In his review of the New York premiere, Andrew Porter wrote that the single idea of each original piece "has, as it were, been passed through a many-faceted bright prism and broken into a thousand linked, lapped, sparkling fragments", the finale "a terse modern Rite ... which sets the pulses racing".

[204] Boulez's ear for sound was legendary: "there are countless stories of him detecting, for example, faulty intonation from the third oboe in a complex orchestral texture", Paul Griffiths wrote in The New York Times.

Chéreau treated the story in part as an allegory of capitalism, drawing on ideas that George Bernard Shaw explored in The Perfect Wagnerite in 1898, and using imagery from the Industrial Age;[90] he achieved an exceptional degree of naturalism in the singers' performances.

In 2005 the Chicago Symphony Orchestra released a 2-CD set of broadcasts by Boulez, focusing on works which he had not recorded commercially, including Janáček's Glagolitic Mass and Messiaen's L'Ascension.

[224] It was with a 1952 article with the inflammatory title "Schoenberg is Dead", published in the British journal The Score shortly after the older composer's death, that Boulez first attracted international attention as a writer.

[226] Jonathan Goldman points out that, over the decades, Boulez's writings addressed very different readerships: in the 1950s the cultured Parisian attendees of the Domaine musical; in the 1960s the specialised avant-garde composers and performers of the Darmstadt and Basel courses; and, between 1976 and 1995, the highly literate but non-specialist audience of the lectures he gave as Professor of the Collège de France.

Jean-Louis Barrault, who knew him in his twenties, caught the contradictions in his personality: "his powerful aggressiveness was a sign of creative passion, a particular blend of intransigence and humour, the way his moods of affection and insolence succeeded one another, all these had drawn us near to him".

"[235] At one point Boulez turned against Messiaen, describing his Trois petites liturgies de la présence divine as "brothel music" and saying that the Turangalîla-Symphonie made him vomit.

He wrote extensively about the painter Paul Klee and owned works by Joan Miró, Francis Bacon, Nicolas de Staël and Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, all of whom he knew personally.

The Philharmonie de Paris is presenting a series of concerts featuring his music; it began with a programme of Répons and other works, played by the Ensemble intercontemporain, joined by former members, the cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras and the pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard.

[264] In August, the Lucerne Summer Festival will feature a rare performance of Poésie pour pouvoir for tape and three orchestras (conducted by David Robertson), as well as Répons, Figures-Doubles-Prismes and other works.

[265] Other series and individual concerts will be presented across the year by the Pierre Boulez Saal in Berlin,[266] the Festspielhaus in Baden-Baden,[267] the London Symphony Orchestra[268] and the Vienna Philharmonic.