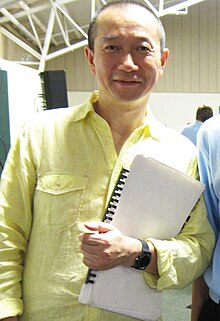

Tan Dun

Tan Dun (Chinese: 谭盾; pinyin: Tán Dùn, Mandarin pronunciation: [tʰǎn tu̯ə̂n]; born 18 August 1957) is a Chinese-born American composer and conductor.

[2] His compositions often incorporate audiovisual elements; use instruments constructed from organic materials, such as paper, water, and stone; and are often inspired by traditional Chinese theatrical and ritual performance.

As a child, he was fascinated by the rituals and ceremonies of the village shaman, which were typically set to music made with natural objects such as rocks and water.

[5] Due to the bans enacted during the Cultural Revolution, he was discouraged from pursuing music and was sent to work as a rice planter on the Huangjin commune.

Following a ferry accident that resulted in the death of several members of a Peking opera troupe, Tan Dun was called upon as a violist and arranger.

[6] While at the Conservatory, Tan Dun came into contact with composers such as Toru Takemitsu, George Crumb, Alexander Goehr, Hans Werner Henze, Isang Yun, and Chou Wen-Chung, all of whom influenced his sense of musical style.

At Columbia, Tan Dun discovered the music of composers such as Philip Glass, John Cage, Meredith Monk, and Steve Reich, and began incorporating these influences into his compositions.

[7] Inspired by a visit to the Museum of Modern Art, Death and Fire is a short symphony that engages with the paintings of Paul Klee.

During his time at Columbia University, Tan Dun composed his first opera, a setting of nature poems by Qu Yuan called Nine Songs (1989).

Among these are a specially built set of 50 ceramic percussion, string, and wind instruments, designed in collaboration with potter Ragnar Naess.

It begins with the spiritual journey of two characters, Marco and Polo, and their encounters with various historic figures of literature and music, including Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, Scheherazade, Sigmund Freud, John Cage, Gustav Mahler, Li Po, and Kublai Khan.

[13] That same year, Tan Dun premiered his next opera, The Peony Pavilion, an adaptation of Tang Xianzu's 1598 Kunqu play of the same name.

Directed by Peter Sellars in its original production, Tan Dun's work is performed entirely in English, though one of the characters must be trained in Peking or Kunqu style.

Like Tan Dun's previous operas, The First Emperor calls for Chinese instruments in addition to a full orchestra, including guzheng and bianzhong.

[18][19][20] Other film credits include the aforementioned Hero (Zhang Yimou, 2002), Gregory Hoblit's Fallen (1998), and Feng Xiaogang's The Banquet (2006).

[21] This same technique was later applied to his film scores for Hero and The Banquet, resulting in the larger work known as the Martial Arts Cycle.

Following years of ethnomusicological research in Hunan, the work captures the sounds of Nüshu script, a phonetic writing system devised by women speakers of the Xiangnan Tuhua dialect who had been disallowed from receiving formal education.

Considered a dying language, Tan Dun's research resulted in a series of short films of women singing songs written in Nüshu, which are presented alongside the orchestral performance.

In the 1990s, Tan Dun began working on a series of orchestral pieces that would analyze the relationship between performer and audience by synthesizing Western classical music and Chinese ritual.

[27]In the first piece of the series, Orchestral Theatre I: O (1990), members of the orchestra make various vocalizations—chanting nonsense syllables, for instance—while playing their instruments using atypical techniques.

While the human conductor leads, the monitors depict a variety of images from the 1960s and the Cold War: a collage of Mao Zedong, the Cultural Revolution, Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy, The Beatles, Nikita Khrushchev, and hydrogen bomb testing.

Written to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the death of Johann Sebastian Bach, the work for chorus, orchestra, and water percussion follows the Gospel of Matthew, beginning with Christ's baptism.

[44] The concerto is reportedly inspired by the composer's love for martial arts, and the soloist is instructed to play certain passages of the music with fists and forearms.

1 "Eroica", was recorded by the London Symphony Orchestra and uploaded to YouTube in November 2008, thus beginning the open call for video audition submissions.

[46] Tan Dun has also conducted the BBC Scottish Symphony to record parts of the album Away from Xuan by fellow composer Chen Yuanlin, released in 2009.