Bowron Lake Provincial Park

Once a popular hunting and fishing destination, today the park is protected and known for its abundant wildlife, rugged glaciated mountains, and freshwater lakes.

Accounts vary in terms of which specific groups these natives belonged to: some settlers speculated these were the Carrier people, while others suggested they were Shuswap or Iroquois.

[4] While very little formal archaeological work has been done, a large number of indigenous artifacts have been seen in the park, including clam middens, old campfires, arrowheads, and cache pits.

[3] As a lingering reminder of the First Nation presence in the area, many of the landmarks and features in and around the park have indigenous names, particularly in the Carrier language.

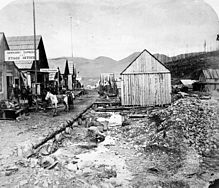

[3] The first major arrival of European settlers in the area around Bowron Lake Park came with the Cariboo Gold Rush in the 1860s, which was centered in the nearby town of Barkerville.

While the Canadian Pacific Survey searched for links through the mountain passes, John Bowron, the Gold Commissioner, sent exploration parties into the hills to establish mining routes into the gold-bearing ground.

One of these routes followed the Goat River pass, connecting the Cariboo region to the Tête Jaune Cache in the Robson Valley, and was well-established enough to allow for dog sleds in the winter.

The most prominent of these guides, Frank Kibbee, started setting up trap lines in the area in 1900[7] and built a home on the shores of Bowron Lake in 1907.

In the 1920s, as concerns were raised about stress on the wildlife population in the Cariboo Mountains, the idea was proposed to turn the area within the Bowron lake quadrangle into a game reserve, citing the success of Yellowstone in the United States.

This was widely supported by naturalists such as Thomas and Elinor McCabe, who had arrived in 1922 and built a home on Indian Point Lake, and Allan Brooks, as well as wilderness guides like the aforementioned Frank Kibbee and Joe Wendle.

Despite some initial resistance from residents of Barkerville, the case was made that the establishment of the reserve would have lasting economic benefits, through the management of the game to sustain the hunting industry.

The oldest is known as the Kaza Group, which is made up of mud and sand deposits that formed during the Precambrian period 600 million years ago, in a sea at the continental margin of what is now the Canadian Shield.

[13] Most of the visible geological features of the park were formed during mountain-building processes that started about 100 million years after the sedimentary and volcanic material was deposited.

[10] Both mountain groups were largely shaped in the Cretaceous period, alongside most of British Columbia's modern drainage channels.

The retreat of the glaciers formed the park's main sequence of lakes in a roughly quadrilateral arrangement, as viewed from space.

[16] Below the tree canopy, the park is home to numerous shrubs and berry plants, which include but are not limited to twinberry, false box, bearberry, Labrador tea, cranberry, huckleberry, mountain ash, red-osier dogwood, soopolallie, white rhododendron, and sticky currant, among others.

Small land-dwelling mammals in the park include various voles and mice, foxes, hares, coyotes, porcupines, skunks, and squirrels.

In addition to its bears, Bowron Lake Park is home to predators like cougars, wolves, wolverines, and lynx.

Notable examples include Canada jays and ravens, which have adapted to human presence and often approach campsites in search of food, and waterfowl such as the loon, whose calls are commonly heard throughout the park.

[16] The central plateau of British Columbia, where Bowron Lake Park resides, has historically been victim to infestations of mountain pine beetle,[21] which can kill large areas of tree forest if not controlled.

The high number of watersheds in the park make it a suitable environment for fish, and many species are widely distributed throughout its waterways.

The circuit spans a total of 116 km and connects almost all of the park's lakes via waterways or short portages on man-made trails.

[26] Since human visitation has a significant impact on the park, several other rules and restrictions have been established, all of which contribute to conservation efforts and/or help maintain the isolated wilderness experience in the circuit.