Branchiosauridae

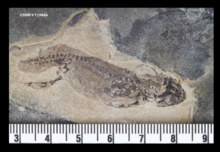

The branchiosaurid fossil record is exceptional due to Lagerstatten conditions of these localities and the preservation of specimens representing various ontogenetic stages.

[4] In the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian, western Europe was subjected to annual and long-lasting changes between dry and monsoon periods which produced highly variable lake environments and thus rapid diversification and speciation of amphibian populations.

[4] A fine lamination of C(org)-rich grey to black shales indicates a belt of lakes of tropical to subtropical climate and the existence of variable levels of oxygen for aquatic life in the Late Paleozoic.

Permo-Carboniferous mass-mortality events are observed in several basins of Germany possibly caused by episodic mixing of the water column resulting in oxygen deficiency.

[2] The synapomorphies of Branchiosauridae include a palatine with a prominent process which extends from the center of the bone to contact the maxilla; six rows of isolated, slender and multi-ended branchials; 21-22 presacral vertebrae (reversed in some forms).

The diagnostic features of the genus Apateon are tabular horns separated from the skull table by a groove; tooth-bearing region of maxilla is broad and the dorsal osteoderms are smooth or with radiating striations.

The Leptorophus-Schoenfelderpeton group is characterized by a postorbital separated from supratemporal, a carotid foramina and grooves situated on sides of the cultriform process.

However, in recent work one such species, Tungussogyriinus bergi has been further analyzed and shown to share clear synapomorphies with branchiosaurids including the Y-shaped palatine resulting in a gap between ectopterygoid and maxilla as well as brush-like branchial denticles.

[9] The specialized pharyngeal denticles with brush-like branches of Branchiosauridae are indicative of gill clefts and suggest a filter-feeding mechanism focusing on plankton.

[10] The jaw-like apparatus may have served to hold back prey items leaving the pharyngeal cavity with the water current or to form a tight closure of gill cleft during feeding.

[2] Branchiosauridae diversified partly through adaptations that included the co-evolution of delayed development of the upper jaw and cheek which resulted in a kinetic maxilla and allowed for more efficient suction feeding.

[2] Although the Melanerpeton-Apateon dichotomy is not correlated with any significant adaptations, the Melanerpeton-clade generally had a larger body size which likely allowed them to occupy new niches in lake ecosystems.

[4] Changes that distinguish the adult A. gracilis from its larval counterpart occurred during a rapid phase of development and include ossification of the braincase, palatoquadrate, intercentra and girdles, muscle attachment scars, and polygonal ridges and grooves decorating the dermal skull roof.

Despite this instance of metamorphosis, neoteny is nearly ubiquitous throughout branchiosaurids and most species remained in an aquatic environment throughout their life (however we should not rule out the possibility that this is a relic of terrestrial metamorphosed specimens not being well preserved).

Skeletochronological analysis allows for the identification of sexual maturity (i.e. when the distance between lines of arrested growth (LAGs) suddenly decreases).

The diaphyseal and epiphyseal ossification patterns of Apateon specimens (i.e. persistence of histological larval features into adulthood) are suggestive of paedomorphy and similar to those of urodeles (extant neotenic amphibians).