Empire of Brazil

Unlike most of the neighboring Hispanic American republics, Brazil had political stability, vibrant economic growth, constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech, and respect for civil rights of its subjects, albeit with legal restrictions on women and slaves, the latter regarded as property and not citizens.

The power vacuum resulting from the absence of a ruling monarch as the ultimate arbiter in political disputes led to regional civil wars between local factions.

Having inherited an empire on the verge of disintegration, Pedro II, once he was legally declared of age, managed to bring peace and stability to the country, which eventually became an emerging international power.

Even though the last four decades of Pedro II's reign were marked by continuous internal peace and economic prosperity, he had no desire to see the monarchy survive beyond his lifetime and made no effort to maintain support for the institution.

[17] Unable to deal with the problems in both Brazil and Portugal simultaneously, the Emperor abdicated on behalf of his son, Pedro II, on 7 April 1831 and immediately sailed for Europe to restore his daughter to her throne.

With no precedent to follow, the Empire was faced with the prospect of a period of more than twelve years without a strong executive, as, under the constitution, Pedro II would not attain his majority and begin exercising authority as Emperor until 2 December 1843.

Believing that granting provincial and local governments greater autonomy would quell the growing dissent, the General Assembly passed a constitutional amendment in 1834, called the Ato Adicional (Additional Act).

[37] While Brazil grappled with this problem, the Praieira revolt, a conflict between local political factions within Pernambuco province (and one in which liberal and courtier supporters were involved), erupted on 6 November 1848, but was suppressed by March 1849.

"[57] This period of calm came to an end in 1863, when the British consul in Rio de Janeiro nearly sparked a war by issuing an abusive ultimatum to Brazil in response to two minor incidents (see Christie Question).

[74] Nonetheless, the "ministry formed by the viscount of Itaboraí was a far abler body than the cabinet it replaced"[73] and the conflict with Paraguay ended in March 1870 with total victory for Brazil and its allies.

[81] In March 1871, Pedro II named the conservative José Paranhos, Viscount of Rio Branco as the head of a cabinet whose main goal was to pass a law to immediately free all children born to female slaves.

The law "split the conservatives down the middle, one party faction backed the reforms of the Rio Branco cabinet, while the second—known as the escravocratas (English: slavocrats)—were unrelenting in their opposition", forming a new generation of ultraconservatives.

[86] By contrast, this new generation of ultraconservatives had not experienced the Regency and early years of Pedro II's reign, when external and internal dangers had threatened the Empire's very existence; they had only known prosperity, peace and a stable administration.

[90] His increasing "indifference towards the fate of the regime"[91] and his inaction to protect the imperial system once it came under threat have led historians to attribute the "prime, perhaps sole, responsibility" for the dissolution of the monarchy to the Emperor himself.

[93] Even though the Constitution allowed female succession to the throne, Brazil was still a very traditional, male-dominated society, and the prevailing view was that only a male monarch would be capable as head of state.

[95] A weary emperor who no longer cared for the throne, an heir who had no desire to assume the crown, an increasingly discontented ruling class who were dismissive of the Imperial role in national affairs: all these factors presaged the monarchy's impending doom.

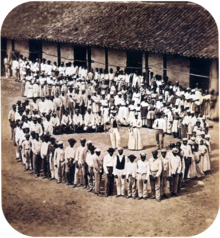

While Pedro II was receiving medical treatment in Europe, the parliament passed, and Princess Isabel signed on 13 May 1888, the Golden Law, which completely abolished slavery in Brazil.

[166] The Army, despite its highly experienced and battle-hardened officer corps, was plagued during peacetime by units which were badly paid, inadequately equipped, poorly trained and thinly spread across the vast Empire.

In 1884, Brazil was called upon to arbitrate between Chile and several other nations (namely France, Italy, Britain, Germany, Belgium, Austria-Hungary and Switzerland) over damages arising from the War of the Pacific.

American historian Steven C. Topik said that Pedro II's "quest for a trade treaty with the United States was part of a grander strategy to increase national sovereignty and autonomy."

Unlike the circumstances of the previous pact, the Empire was in a strong position to insist on favorable trade terms, as negotiations occurred during a time of Brazilian domestic prosperity and international prestige.

[207] The "countryside echoed with the clang of iron track being laid as railroads were constructed at the most furious pace of the 19th century; indeed, building in 1880s was the second greatest in absolute terms in Brazil's entire history.

[211] In addition to the foregoing improvements to infrastructure, it was also the first South American nation to adopt public electric lighting (in 1883)[212] and the second in the Americas (behind the United States) to establish a transatlantic telegraphic line connecting it directly to Europe in 1874.

The majority of the population of Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo, Bahia, Sergipe, Alagoas, and Pernambuco provinces (the last four having the smallest percentages of whites in the whole country—less than 30% in each) were black or brown.

[257] In the 1830s, due to the instability of the Regency, European immigration ground to a halt, only recovering after Pedro II took the reins of government and the country entered a period of peace and prosperity.

[298] As Catholicism was the official religion, the emperor exercised a great deal of control over Church affairs[298] and paid clerical stipends, appointed parish priests, nominated bishops, ratified papal bulls and supervised seminaries.

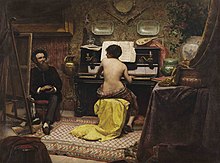

[314] It was only following Pedro II's majority in 1840, however, that the academy became a powerhouse, part of the Emperor's greater scheme of fomenting a national culture and consequently uniting all Brazilians in a common sense of nationhood.

[317] That sponsorship would pave the way not only for the careers of artists, but also for those engaged in other fields, including historians such as Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen[318] and musicians such as the operatic composer Antônio Carlos Gomes.

[325] During the 1830s and 1840s, "a network of newspapers, journals, book publishers and printing houses emerged which together with the opening of theaters in the major towns brought into being what could be termed, but for the narrowness of its scope, a national culture".

[333] Less prestigious, but more popular with the working classes were puppeteers and magicians, as well as the circus, with its travelling companies of performers, including acrobats, trained animals, illusionists, and other stunt-oriented artists.