Romanticism

With this philosophical foundation, the Romanticists elevated several key themes to which they were deeply committed: a reverence for nature and the supernatural, an idealization of the past as a nobler era, a fascination with the exotic and the mysterious, and a celebration of the heroic and the sublime.

[2] A confluence of circumstances led to Romanticism's decline in the mid-19th century, including (but not limited to) the rise of Realism and Naturalism, Charles Darwin's publishing of the Origin of Species, the transition from widespread revolution in Europe to a more conservative climate, and a shift in public consciousness to the immediate impact of technology and urbanization on the working class.

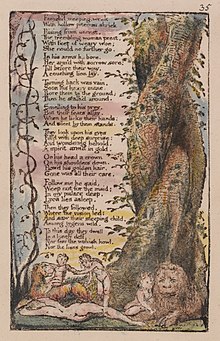

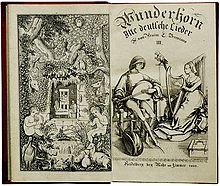

In contrast to the rationalism and classicism of the Enlightenment, Romanticism revived medievalism[12] and juxtaposed a pastoral conception of a more "authentic" European past with a highly critical view of recent social changes, including urbanization, brought about by the Industrial Revolution.

Romanticism lionized the achievements of "heroic" individuals—especially artists, who began to be represented as cultural leaders (one Romantic luminary, Percy Bysshe Shelley, described poets as the "unacknowledged legislators of the world" in his "Defence of Poetry").

"[22] This quality in Romantic literature, in turn, influenced the approach and reception of works in other media; it has seeped into everything from critical evaluations of individual style in painting, fashion, and music, to the auteur movement in modern filmmaking.

[27] In England Wordsworth wrote in a preface to his poems of 1815 of the "romantic harp" and "classic lyre",[27] but in 1820 Byron could still write, perhaps slightly disingenuously, It is only from the 1820s that Romanticism certainly knew itself by its name, and in 1824 the Académie française took the wholly ineffective step of issuing a decree condemning it in literature.

This is most evident in the aesthetics of romanticism, where the notion of eternal models, a Platonic vision of ideal beauty, which the artist seeks to convey, however imperfectly, on canvas or in sound, is replaced by a passionate belief in spiritual freedom, individual creativity.

Byron had equal success with the first part of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage in 1812, followed by four "Turkish tales", all in the form of long poems, starting with The Giaour in 1813, drawing from his Grand Tour, which had reached Ottoman Europe, and orientalizing the themes of the Gothic novel in verse.

[52] In contrast to Germany, Romanticism in English literature had little connection with nationalism, and the Romantics were often regarded with suspicion for the sympathy many felt for the ideals of the French Revolution, whose collapse and replacement with the dictatorship of Napoleon was, as elsewhere in Europe, a shock to the movement.

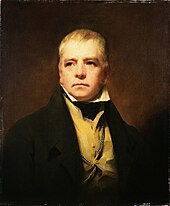

Though they have modern critical champions such as György Lukács, Scott's novels are today more likely to be experienced in the form of the many operas that composers continued to base on them over the following decades, such as Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor and Vincenzo Bellini's I puritani (both 1835).

[66][67] Ian Duncan and Alex Benchimol suggest that publications like the novels of Scott and these magazines were part of a highly dynamic Scottish Romanticism that by the early nineteenth century, caused Edinburgh to emerge as the cultural capital of Britain and become central to a wider formation of a "British Isles nationalism".

Towards the end of the century there were "closet dramas", primarily designed to be read, rather than performed, including work by Scott, Hogg, Galt and Joanna Baillie (1762–1851), often influenced by the ballad tradition and Gothic Romanticism.

His writings, all in prose, included some fiction, such as his influential novella of exile René (1802), which anticipated Byron in its alienated hero, but mostly contemporary history and politics, his travels, a defence of religion and the medieval spirit (Génie du christianisme, 1802), and finally in the 1830s and 1840s his enormous autobiography Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe ("Memoirs from beyond the grave").

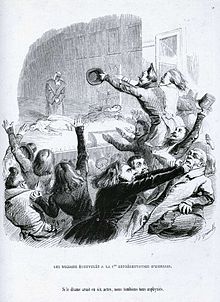

[71] Alexandre Dumas began as a dramatist, with a series of successes beginning with Henri III et sa cour (1829) before turning to novels that were mostly historical adventures somewhat in the manner of Scott, most famously The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo, both of 1844.

Stendhal is today probably the most highly regarded French novelist of the period, but he stands in a complex relation with Romanticism, and is notable for his penetrating psychological insight into his characters and his realism, qualities rarely prominent in Romantic fiction.

Early Russian Romanticism is associated with the writers Konstantin Batyushkov (A Vision on the Shores of the Lethe, 1809), Vasily Zhukovsky (The Bard, 1811; Svetlana, 1813) and Nikolay Karamzin (Poor Liza, 1792; Julia, 1796; Martha the Mayoress, 1802; The Sensitive and the Cold, 1803).

While living in Great Britain, he had contacts with the Romantic movement and read authors such as Shakespeare, Scott, Ossian, Byron, Hugo, Lamartine and de Staël, at the same time visiting feudal castles and ruins of Gothic churches and abbeys, which would be reflected in his writings.

An early Portuguese expression of Romanticism is found already in poets such as Manuel Maria Barbosa du Bocage (especially in his sonnets dated at the end of the 18th century) and Leonor de Almeida Portugal, Marquise of Alorna.

American Romantic Gothic literature made an early appearance with Washington Irving's "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" (1820) and "Rip Van Winkle" (1819), followed from 1823 onwards by the Leatherstocking Tales of James Fenimore Cooper, with their emphasis on heroic simplicity and their fervent landscape descriptions of an already-exotic mythicized frontier peopled by "noble savages", similar to the philosophical theory of Rousseau, exemplified by Uncas, from The Last of the Mohicans.

Edgar Allan Poe's tales of the macabre and his balladic poetry were more influential in France than at home, but the romantic American novel developed fully with the atmosphere and drama of Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter (1850).

Like the Europeans, the American Romantics demonstrated a high level of moral enthusiasm, commitment to individualism and the unfolding of the self, an emphasis on intuitive perception, and the assumption that the natural world was inherently good, while human society was filled with corruption.

[97] In Britain, notable examples include the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, a romantic version of traditional Indian architecture by John Nash (1815–1823), and the Houses of Parliament in London, built in a Gothic revival style by Charles Barry between 1840 and 1876.

Théodore Géricault (1791–1824) had his first success with The Charging Chasseur, a heroic military figure derived from Rubens, at the Paris Salon of 1812 in the years of the Empire, but his next major completed work, The Raft of the Medusa of 1818–19, remains the greatest achievement of the Romantic history painting, which in its day had a powerful anti-government message.

When it did develop, true Romantic sculpture—with the exception of a few artists such as Rudolf Maison[109]—rather oddly was missing in Germany, and mainly found in France, with François Rude, best known from his group of the 1830s from the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, David d'Angers, and Auguste Préault.

Fleury-Richard's Valentine of Milan weeping for the death of her husband, shown in the Paris Salon of 1802, marked the arrival of the style, which lasted until the mid-century, before being subsumed into the increasingly academic history painting of artists like Paul Delaroche.

[112] Another trend was for very large apocalyptic history paintings, often combining extreme natural events, or divine wrath, with human disaster, attempting to outdo The Raft of the Medusa, and now often drawing comparisons with effects from Hollywood.

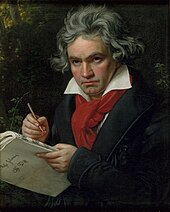

Public persona characterized a new generation of virtuosi who made their way as soloists, epitomized in the concert tours of Paganini and Liszt, and the conductor began to emerge as an important figure, on whose skill the interpretation of the increasingly complex music depended.

[118] This is of particular interest because it is a French source on a subject mainly dominated by Germans, but also because it explicitly acknowledges its debt to Jean-Jacques Rousseau (himself a composer, amongst other things) and, by so doing, establishes a link to one of the major influences on the Romantic movement generally.

In Haydn's music, according to Hoffmann, "a child-like, serene disposition prevails", while Mozart (in the late E-flat major Symphony, for example) "leads us into the depths of the spiritual world", with elements of fear, love, and sorrow, "a presentiment of the infinite ... in the eternal dance of the spheres".

[130] In England, Thomas Carlyle was a highly influential essayist who turned historian; he both invented and exemplified the phrase "hero-worship",[131] lavishing largely uncritical praise on strong leaders such as Oliver Cromwell, Frederick the Great and Napoleon.