Independence of Brazil

The army immediately opposed the Portuguese forces, which controlled some parts of the country, namely, in the then provinces of Cisplatina (currently Uruguay), Bahia, Piauí, Maranhão and Grão-Pará.

At the same time that the conflict was taking place, a revolutionary movement broke out in Pernambuco and other neighboring provinces, which intended to form their own country, the Confederation of the Equator, with a republican government, but it was harshly repressed.

In exchange for recognition as a sovereign state, Brazil committed to paying a substantial compensation to Portugal and signing two treaties with the United Kingdom by which it agreed to ban the Atlantic slave trade and grant preferential tariffs to British goods imported into the country.

The land now called Brazil was claimed by the Kingdom of Portugal in April 1500, on the arrival of the Portuguese naval fleet commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral.

[citation needed] Though the first settlement was founded in 1532, colonization only effectively started in 1534 when King John III divided the territory into fifteen hereditary captaincies.

They sent military expeditions to the northwest of the South American continent to the Amazon River basin rainforest and conquered competing English and Dutch strongholds, founding villages and forts from 1669.

In 1680 they reached the far southeast and founded Colônia do Sacramento on the bank of the Río de la Plata, in the Banda Oriental region (present-day Uruguay).

[citation needed] At the end of the 17th century, sugar exports started to decline, but beginning in the 1690s, the discovery of gold by explorers in the region that would later be called Minas Gerais, current Mato Grosso and Goiás saved the colony from imminent collapse.

[citation needed] The Spanish tried to prevent Portuguese expansion northwest, west, southwest and southeast into the territory that belonged to them according to the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas division of the New World by the Bishop and Pope of Rome, Alexander VI (1431–1503, reigned 1492–1503) and succeeded in conquering the Banda Oriental region in 1777.

However, this was in vain as the Treaty of San Ildefonso, signed in the same year, confirmed Portuguese sovereignty over all lands proceeding from its territorial expansion, thus creating most of the current Brazilian southeastern border.

[5][6] The king left for Europe on 26 April, while Dom Pedro remained in Brazil governing it with the aid of the ministers of the Kingdom (Interior) and Foreign Affairs, of War, of Navy and of Finance.

[14] His wife, princess Maria Leopoldina of Austria, favoured the Brazilian side and encouraged him to remain in the country[18] which the Liberals and Bonifacians openly called for.

[20] Dom Pedro then "dismissed" the Portuguese commanding general and ordered him to remove his soldiers across the bay to Niterói, where they would await transport to Portugal.

[23] Gonçalves Ledo and the Liberals tried to minimize the close relationship between Bonifácio and Pedro, offering to the prince the title of Perpetual Defender of Brazil.

[24] The prince acquiesced to the Liberals’ desires, and signed a decree on 3 June 1822 calling for the election of deputies that would gather in a Constituent and Legislative General Assembly in Brazil.

[citation needed] The letter told him that the Cortes had annulled all acts of the Bonifácio cabinet, removed Pedro's remaining powers, and ordered him to return to Portugal.

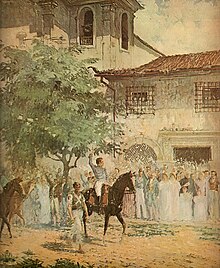

He unsheathed his sword affirming that "For my blood, my honor, my God, I swear to give Brazil freedom," and later cried out: "Brazilians, Independence or death!".

[28][29] Pedro returned to Rio de Janeiro on 14 September and in the following days the Liberals had distributed pamphlets (written by Joaquim Gonçalves Ledo) that suggested that the Prince should be named Constitutional Emperor.

Loyal militias began insurrections in the aforementioned territories, but strong, and regularly reinforced Portuguese garrisons in the port cities of Salvador, Montevideo, São Luís and Belém continued to dominate the adjacent areas and to pose the threat of a reconquest that the irregular Brazilian militias and guerrilla forces, which were loosely besieging them by land supported by newly created units of the Brazilian army, would be unable to prevent.

The Brazilian Government solved the problem by recruiting 50 officers and 500 seamen in secret in London and Liverpool, many of them veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, and appointed Thomas Cochrane as commander-in-chief.

Deprived now of supplies and reinforcements by sea and besieged by the Brazilian army on land, on 2 July the Portuguese forces abandoned Bahia in a convoy of 90 ships.

Leaving the frigate ‘Niteroi’ under Captain John Taylor to harry them to the coasts of Europe, Cochrane then sailed north to São Luís (Maranhão).

But this meant that independent Brazil retained its colonial social structure: monarchy, slavery, large landed estates, monoculture, an inefficient agricultural system, a highly stratified society, and a free population that was 90 percent illiterate.