Imperial Brazilian Army

[4] In 1822 and 1823, the Imperial Army was able to defeat the Portuguese resistance, especially in the north of the country and in Cisplatina, also preventing the fragmentation of the newly proclaimed Brazilian Empire after its independence war.

It repressed a host of popular movements for political autonomy or against slavery and the large landowners' power across Brazil.

[6] During the 1850s and early 1860s, the Army, along with the Navy, entered in action against Argentine and Uruguayan forces, which were opposed to the Brazilian empire's interests.

The Brazilian success with such "Gun Diplomacy" eventually led to a shock of interests with another country with similar aspirations, Paraguay, in December 1864.

In November 1889, after a long attrition with the monarchical regime deepened by the abolition of slavery, the army led a coup d'état that resulted in the end of the empire and the founding of a republic.

The implementation of the first Brazilian military dictatorship (that ended in 1894), was followed by a severe economic crisis that deepened into an institutional one with Congress and the Navy, which degenerated into a civil war in the southern region.

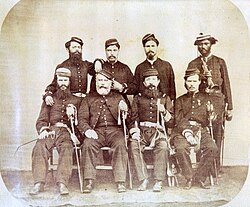

Army officers' training was completed in the Imperial Military Academy,[16] although it was not obligatory for personnel to study there to advance in the profession.

The Porto Alegre college location provided courses in infantry and cavalry, including disciplines taken from the 1st and 5th years of study.

[21] The National Guard was reorganized in the same month and became subordinate directly to the Minister of Justice, instead of to the locally elected Judges of Peace.

[25][26] These were replaced in the Empire of Brazil by the National Guard, whose recruitment (called "enlistment") was complementary and antagonistic, absorbing personnel of a higher social level.

[33] In Europe, a reference for the Brazilian elite, the period after the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) was marked by industrialization, states with greater control over their populations and conscript armies, which, after 1–3 years of service, followed into a growing reserve.

In the aftermath, the military blamed the Emperor for not being able to convince the Parliament to allow more financial aid to purchase equipment, munitions and provisions, while the liberals, on the other hand, considered the monarch responsible for the high costs of the conflict.

The election of the conservative Pedro de Araújo Lima for the office of regent in 1837 completely changed the situation.

[42] The Imperial Army achieved several victories over the provincial revolts, including: Cabanagem, Sabinada, Ragamuffin War, among others.

[14] In 1851 the Imperial Army was composed of more than 37,000[12] men which 20,000 participated in the Platine War against the Argentine Confederation which opposed to Brazilian Empire's interests.

[52] The Marquis of Caxias reorganized the troops who received uniforms, equipment and weapons equal in quality to those of the Prussian Army.

The Imperial Army mobilized 154,996 men for the war, divided into the following categories: 10,025 Army personnel who were in Uruguay in 1864; 2,047 in the province of Mato Grosso; 55,985 Fatherland Volunteers; 60,009 National Guardsmen; 8,570 ex-slaves; and an additional 18,000 National Guardsmen who remained in Brazil to defend their homeland.

The army, unlike the Imperial Navy, suffered with much less investment, especially during the regency, rendering it inadequate, ill-trained, and ill-armed.

A new generation of turbulent and undisciplined military personnel began to appear at the beginning of the 1880s, because the old monarchist officers, such as Duke of Caxias, Polidoro da Fonseca Quintanilha Jordão (Viscount of Santa Teresa), Antonio de Sampaio, Manuel Marques de Sousa, Count of Porto Alegre and Manuel Luís Osório, Marquis of Erval were dead.

[59][60] The republicans stimulated the undisciplined behavior of these personnel during 1887 and 1888 by alleging a lack of attention and consideration on the part of the Government towards the Army.

[61] On 15 November 1889, the monarchy was overthrown by Army troops led by Field Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca who became the leader of the First Brazilian Republic, known as Sword Dictatorship.

[63] In the following days several battalions of the Army, which were spread across the country, fought against republican forces with the intention of stopping the coup.