Brazilian Romantic painting

Characterized by a palatial and restrained aesthetic, it incorporated a strong neoclassical influence and gradually integrated elements of Realism, Symbolism, and other schools, resulting in an eclectic synthesis that dominated the Brazilian art scene until the early 20th century.

Their artistic judgments were not guided by prevailing rationalism or predetermined aesthetic programs, but rather by their own subjective experience, which could encompass a range of emotions, including a yearning for a connection with nature or the transcendent.

Furthermore, a prevalent sentiment of the era, often referred to as the mal du siècle, characterized by a sense of emptiness, futility, and melancholic dissatisfaction, permeated the works of many artists.

[9] The roots of Brazilian Romantic painting, though achieving dominance only between 1850 and 1860, can be traced back to the early 19th century, which coincided with the arrival of numerous foreign naturalists on scientific expeditions.

Notably, he was struck by the concept of "banzo", a term used by enslaved people to describe their melancholy, and depicted this theme in several watercolors, including the well-known "Tattooed Black Woman Selling Cashews".

Debret's extensive watercolor collection, compiled in his publication Picturesque and Historical Travel to Brazil, offers a valuable human and artistic document of Brazilian life during his time.

This work marks a significant shift away from Neoclassicism, replaced by an empathetic and naturalistic depiction of enslaved people, reflecting a characteristically Romantic humanist perspective.

Furthermore, the nascent urbanization process, with its evolving boundaries, provided fertile ground for the depiction of city life, aligning with the unifying spirit traditionally associated with European Romantic landscape painting.

However, as scholar Vera Siqueira suggests, a distinctive characteristic of the Brazilian experience lies in: All this picturesque vision of the city is related to the European intellectual scheme that, since Rousseau, tends to think of nature as a space of purity, of physical and spiritual health.

[13]Beyond the contributions of itinerant painters and antecedent poets like Maciel Monteiro,[14] a group of intellectuals active from the 1830s onwards, following the Independence of Brazil, played a pivotal role in initiating the nation's Romantic movement.

Emperor Pedro II emerged as a significant patron of this movement, fostering a series of debates concerning the political, economic, cultural, and social trajectory they envisioned for the new nation.

One notable development was the establishment of the Royal School of Sciences, Arts and Crafts, a precursor to the Imperial Academy, which contributed to a temporary flourishing of cultural life in Rio de Janeiro.

[2][1] Brazilian Romanticism reached its peak during a period when the movement in Europe had already entered its later stages, characterized by a shift towards catering to the tastes of the affluent and established middle class.

Documents from the period consistently highlight recurring difficulties, including a shortage of qualified instructors and equipment, along with the inadequate preparation of students, some of whom exhibited basic literacy deficiencies.

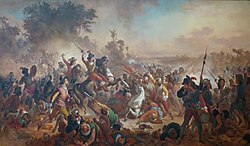

This period of improved resources provided fertile ground for the flourishing of Brazilian Romantic painting, fostering the emergence of prominent figures such as Victor Meirelles, Pedro Américo, Rodolfo Amoedo and Almeida Júnior.

These artists built upon the foundational work of Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre, whose contributions were instrumental in developing a symbolic visual language capable of unifying the nationalist movement active during this period.

The Academy's focus centered on portraiture, particularly of members of the new ruling house, and historical scenes depicting pivotal national events such as battles that secured Brazil's territorial integrity and sovereignty, the independence movement, and the role of indigenous people.

Emperor Pedro II's nationalist project was inherently optimistic and fundamentally opposed to the ultra-sentimental and morbid characteristics of the second generation of Romantic writers, often referred to as the "bohemians" who grappled with the mal du siècle.

[21][20] While the Imperial Academy's emphasis on rigid aesthetic principles and its reliance on government approval did restrict the expression of artistic independence and originality, a hallmark of European Romanticism.

As previously noted, the delayed emergence of Romanticism in Brazil meant it was primarily influenced by the waning stages of the movement in Europe, particularly French Pompier art, which is characterized by its bourgeois nature, emphasis on conformity, eclecticism, and sentimentality.

Consequently, the image of Brazil he sought to present to the world was inevitably selective, favoring portrayals of the landscape that adhered to European formal styles and overlooking negative social realities such as slavery.

[2][1] Beyond the core thematic areas of historical scenes, landscapes, portraits of the imperial family, and depictions of Indigenous and working-class people, Brazilian Romantic painting encompassed a wider range of subjects.

[...] Young people, leave the prejudice of longing for public jobs, the telethon of the offices, which ages you prematurely, and condemns you to poverty and to a continuous slavery; apply yourselves to arts and industry: the arm that was born to be an ass or a trowel should not handle the pen.

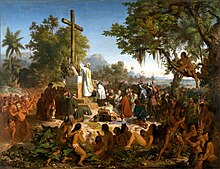

Art historian Jorge Coli argues that "First Mass in Brazil" achieves a rare confluence of form, intention, and meaning, solidifying the painting's powerful influence on Brazilian culture.

Art critic Gonzaga Duque suggests that Amoedo's artistic achievement reached its peak with paintings such as "Jacob's Departure", "The Narration of Philéctas", and "Bad News".

[obsolete source] In addition to the previously mentioned artist-explorers who played a pioneering role in Brazilian Romanticism, a significant number of foreign artists contributed to the movement during its peak and the Imperial Academy's operation.

However, more recent scholarship conducted within a broader historical context acknowledges the presence of a well-defined Romantic style in Brazilian art, albeit confined to the realm of "academic Romanticism."

Furthermore, they overlooked the enduring influence of Brazil's Baroque heritage, which continued to manifest in various regional artistic expressions and popular culture, largely unaffected by developments in Rio de Janeiro.

Exhibited at the 1879 Salon, these paintings drew a remarkable audience exceeding 292,000 visitors over a 62-day period.This level of engagement remains unmatched even by contemporary events like the São Paulo Art Biennials, considering Rio de Janeiro's population of just over 300,000 at the time.

The Romantic movement's portrayal of Indigenous people in a more sympathetic light, along with its positive depictions of other working-class figures, can be seen as an early step towards greater national integration.