Brian Clarke

Born to a working-class family in Oldham, in the north of England, and a full-time art student on scholarship by age 13, Clarke came to prominence in the late 1970s as a painter and figure of the Punk movement[5][6][7] and designer of stained glass.

His practice in architectural and autonomous stained glass, often on a monumental scale,[12] has led to successive innovation and invention in the development of the medium.

[28] In place of a standard curriculum, he principally studied the arts and design, learning drawing, heraldry, pictorial composition, colour theory, pigment mixing and calligraphy, among other subjects.

In his career, Clarke has advanced new approaches across a range of mediums including stained glass, mosaic, collage, painting and drawing.

In 1976, Clarke received a large-scale commission from the University of Nottingham to produce 45 paintings, vestments, and a series of stained glass windows for a multi-faith chapel in the Queen's Medical Centre.

[34] The resulting end of this relationship freed Clarke to create stained glass for secular contexts and advance the medium as social art.

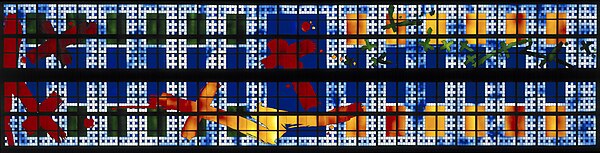

In his painting, Clarke developed a strictly abstract Constructivist language of geometric signs; often his work had an underlying grid structure made from repetitions and variations on the cross.

He connected with Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren and later collaborated as a designer on their aborted zine Chicken, whose creation was funded by EMI and filmed by BBC's Arena.

The programme and subsequent press coverage, including Clarke's appearance on the cover of Vogue, photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe, brought him to broader public attention.

He received his first international commission for paintings, a wooden construction, and a suite of stained glass windows for the Olympus European Headquarters Building in Hamburg, completed in 1981.

In the same year, receiving a commission from the Government of Saudi Arabia for the Royal Mosque of King Khalid International Airport, Clarke studied Islamic ornament at the Quran schools in Fez.

Following this, in 1984, the architectural practice Derek Latham and Co. asked Clarke to collaborate on the refurbishment of Henry Currey's Grade II listed Thermal Baths in Buxton.

Satisfying his public ambitions for the medium, he enclosed the former Victorian spa in a barrel-vaulted skin of stained glass, bathing the space “in an immense blue light”.

[44] Clarke designed a composition of stained glass for the central lantern[45] and a series of interrelated skylights that referenced elements of Isozaki's building.

While their abstract, constructivist forms resonated with Foster's language, Clarke has recently expressed how the medieval technology of lead and stained glass was at odds with the material qualities of High-tech architecture.

When Future Systems (the architectural practice of Jan Kaplický and Amanda Levete) asked Clarke to collaborate on The Glass Dune (1992), he proposed an internal ‘skin of art’ for their innovative boomerang-shaped building, which was never realised.

Working with architect Zaha Hadid on a proposal for the Spittelau Viaducts Housing Project, Vienna, he developed a new type of mouth-blown glass, which he christened 'Zaha-Glas'.

Clarke brought a second court case against Marlborough Fine Art, alleging that the gallery had underpaid Bacon for his work, asserted undue influence over him,[52] and failed to account for up to 33 of his paintings.

During the legal process an undisclosed number of Bacon's paintings were recovered from Marlborough, and "vast quantities of correspondence and documents relating to the life of the artist were handed over by the gallery".

A decision was taken to preserve the studio as it stood, and a team of archaeologists, art historians, conservators, and curators were involved in the move from London to Dublin.

Clarke worked with Norman Foster on the Palace of Peace and Reconciliation, a landmark building in Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan, built to house the triennial Congress of Leaders of World and Traditional Religions.

[62] Clarke's collages are equally experimental; the carefully chosen, often torn, fragments and chalk drawings build an image that attempts to capture the essence of the flower depicted.

The work received criticism when it was shown at Christie's, London in 2011, reflective of the traditionalist values that surround the medium of stained glass.

Clarke also designed the stained glass windows for the new extension to Westminster Coroner's Court, which opened in 2024; The Guardian's Rowan Moore described them as "realised with virtuosity in the handling of depth and density of colour, meant to convey growth and renewal"; Clarke himself explained that the windows were intended "not to give people an artistic ecstasy, but to say ‘I am with you’, ‘I know what you’re going through’, to put an arm around people’s shoulders.