British European Airways Flight 548

It also cited the captain's undiagnosed heart condition and the limited experience of the co-pilot while noting an unspecified "technical problem" that the crew apparently resolved before take-off.

On Monday 19 June 1972, the day following the accident, the International Federation of Air Line Pilots' Associations (IFALPA) had declared, as a worldwide protest, a strike action against aircraft hijacking, which had become commonplace in the early 1970s.

A group of twenty-two BEA Trident co-pilots known as supervisory first officers (SFOs) were already on strike, citing their low status and high workload.

As a result of being limited to the P3 role, BEA Trident SFOs/P3s were denied experience of aircraft handling, which led to loss of pay, which they resented.

"[5] An hour and a half before the departure of Flight 548, its rostered captain, Stanley Key, a former Royal Air Force pilot who had served during the Second World War, was involved in a quarrel in the crew room at Heathrow's Queens Building with a first officer named Flavell.

[7] Key's anti-strike views had won enemies, and graffiti against him had appeared on the flight decks of BEA Tridents, including the incident aircraft, G-ARPI (Papa India).

[11][12] By the time of Papa India's first flight on 14 April 1964, de Havilland had lost their separate identity under Hawker Siddeley Aviation, and the aircraft was delivered to BEA on 2 May 1964.

Random checks carried out by BEA after the accident showed that this was not the case; twenty-one captains stated that they had witnessed their co-pilots react correctly to any stall warnings.

[19] The Confidential Human Factors Incident Reporting Programme (CHIRP), an experimental, voluntary, anonymous and informal system of reporting hazardous air events introduced within BEA in the late 1960s (and later adopted by the Civil Aviation Authority and the Federal Aviation Administration), brought to light two near-accidents, the "Orly" and "Naples" incidents: these involved flight crew error in the first case and suspicion of the Trident's control layout in the second case.

[20][21] In December 1968, the captain of a Trident 1C departing Orly Airport for London tried to improve climb performance by retracting the flaps shortly after take-off.

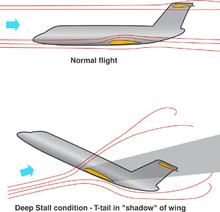

[22] In the second near-accident, a Trident 2E (G-AVFH) climbing away from London Heathrow for Naples in May 1970 experienced what was claimed by its flight crew to have been a spontaneous uncommanded retraction of the leading-edge slats which was initially unnoticed by any of them.

[23] Investigations into this incident found no mechanical malfunction that could have caused the premature leading-edge device retraction, and stated that the aircraft had "just about managed to stay flying.

[35][36] The "deadheading" crew was led by Captain John Collins, an experienced former Trident first officer, who was allocated the observer's seat on the flight deck.

[39][40] At 16:08:30 Flight 548 began its take-off run, which lasted forty-four seconds, the aircraft leaving the ground at an indicated airspeed (IAS) of 145 knots (269 km/h; 167 mph).

[38] At 16:09:44 (seventy-four seconds after the start of the take-off run), passing 690 feet (210 m), Key began the turn towards the Epsom NDB and reported that he was climbing as cleared and the flight entered cloud.

Key pulled the nose up once more to reduce airspeed slightly, to the normal 'droops extended' climb speed of 177 knots (328 km/h; 204 mph), which further stalled the aircraft.

[51] A BEA captain, Eric Pritchard, arrived soon after the bodies had been removed; he noted the condition of the wreckage and drew conclusions:[50] The aircraft had impacted in a high-nose-up attitude.

I noticed that the droops and flaps were retracted.The accident was the worst air disaster in the United Kingdom until the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing over Lockerbie, Scotland, in 1988.

Proceedings were often adversarial, with counsel for victims' families regularly attempting to secure positions for future litigation, and deadlines were frequently imposed on investigators.

[40] The wreckage of Papa India was then moved to a hangar at the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough, Hampshire, for partial re-assembly aimed at checking the integrity of its flight control systems.

[61] In other words, Key could have suffered it at any time between the row in the Queens Building crewroom and ninety seconds after the start of the take-off run (the instant of commencing noise abatement procedures).

[64] It was opened by Geoffrey Wilkinson of the AIB with a description of the accident, and counsel for the relatives of the crew members and passengers then presented the results of their private investigations.

In particular, Lee Kreindler of the New York City Bar presented claims and arguments that were considered tendentious and inadmissible by pilots and press reporters.

The bare facts being more-or-less uncovered soon after the event, the inquiry was frustrated by the lack of a cockpit voice recorder fitted to the accident aircraft.

A three-way air pressure valve (part of the stall recovery system) was found to have been one sixth of a turn out of position, and the locking wire which secured it was missing.

[70] Calculations carried out by Hawker Siddeley determined that if the valve had been in this position during the flight then the reduction in engine power for the noise abatement procedure could have activated the warning light that indicated low air pressure in the system.

[57] A captain who had flown Papa India on the morning of the accident flight noted no technical problems, and the public inquiry found that the position of the valve had no significant effect on the system.

[73] Although the report covered the state of industrial relations at BEA, no mention was made of it in its conclusions, despite the feelings of observers that it intruded directly and comprehensively onto the aircraft's flight deck.

[43] Sources close to the events of the time suggest that Collins played an altogether more positive role by attempting to lower the leading-edge devices in the final seconds of the flight; Eric Pritchard, a Trident captain who happened to be the first airman at the accident site, recalled that a fireman had stated that Collins was lying across the centre pedestal and noted himself that his earphones had fallen into the right-hand-side footwell of the flight deck, diagonally across from the observer's seat, as might be expected if he had attempted to intervene as a last resort.

[77][78] The accident led to a much greater emphasis on crew resource management training, a system of flight deck safety awareness that remains in use today.