Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571

He mistakenly believed the aircraft had overflown Curicó, the turning point to fly north, and began descending towards what he thought was Pudahuel Airport in Santiago de Chile.

The remaining portion of the fuselage slid down a glacier at an estimated 350 km/h (220 mph), descending 725 metres (2,379 ft) before ramming into an ice and snow mound.

The flight was carrying 45 passengers and crew, including 19 members of the Old Christians Club rugby union team, along with their families, supporters and friends.

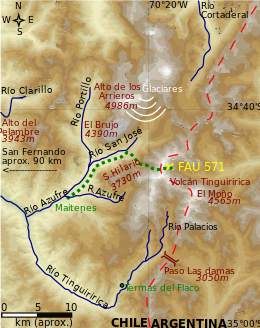

The crash site is located at an elevation of 3,660 metres (12,020 ft) in the remote Andes mountains of western Argentina, just east of the border with Chile.

[2] During the 72 days following the crash, the survivors suffered from extreme hardships, including sub-zero temperatures, exposure, starvation, and an avalanche, which led to the deaths of 13 more passengers.

[3] Club president Daniel Juan chartered a Uruguayan Air Force twin turboprop Fairchild FH-227D airplane to fly the team over the Andes mountains to Santiago.

[3] The aircraft departed Carrasco International Airport on 12 October 1972, but a storm front over the Andes forced them to spend the night in Mendoza, Argentina, to wait for meteorological conditions to improve.

The controller authorized the aircraft to descend to 3,500 metres (11,500 ft), unaware due to lack of radar coverage that the airplane was still flying over the Andes.

[6][3] The aircraft's momentum and its remaining engine carried it forward and upward until a rock outcropping at 4,400 metres (14,400 ft) tore off the left wing.

[8][20] The plane's fuselage came to rest in the cirque of the Glaciar de las Lágrimas or Glacier of Tears at 34°45′53.5″S 70°17′06.6″W / 34.764861°S 70.285167°W / -34.764861; -70.285167 at an elevation of 3,675 metres (12,057 ft), in the Malargüe Department in the Mendoza Province of Argentina.

Unbeknownst to the passengers or the search teams, the flight had crashed in Argentina even before crossing into Chile, about 21 km (13 mi) from the Hotel Termas el Sosneado, an abandoned hot springs resort.

Another five passengers and crew died between the first night and next day: co-pilot Lagurara, Francisco Abal, Graziela Mariani, Felipe Maquirriain and Julio Martinez-Lamas.

To prevent snow blindness, he also improvised sunglasses by cutting the green plastic sun visors in the cockpit and sewing the pieces to bra straps with electrical wire.

Roy Harley improvised a long antenna using electrical wire from the plane[7] and on the eleventh day on the mountain heard the news that their search had been called-off.

Piers Paul Read's book Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors describes how they reacted: The others who had clustered around Roy, upon hearing the news, began to sob and pray, all except [Nando] Parrado, who looked calmly up at the mountains which rose to the west.

[3] In his memoir, Miracle in the Andes: 72 Days on the Mountain and My Long Trek Home (2006), Parrado wrote about this decision: At high altitude, the body's caloric needs are astronomical.

[31][28] On the morning of 31 October they were able to dig an exit tunnel with considerable difficulty from the cockpit to the surface, only to be faced with a blizzard that made them crawl back into the fuselage.

Canessa, Parrado and Vizintín were among the most physically fit and were allocated larger rations of meat to build their strength for the expedition and the warmest clothes to withstand the night-time cold they would have to face on the mountain.

On 15 November after several hours of walking 1.6 km (1 mi) downhill east of the fuselage, they found the tail section of the aircraft with the galley mostly intact.

They gave up after several days of not being able to make the radio work and returned to the fuselage realizing they would have to climb out of the mountains on their own terms to get help if they were to have any chance of surviving.

Numa Turcatti, whose extreme revulsion against eating human flesh dramatically accelerated his physical decline, died on day 60 (11 December) weighing only 25 kg (55 pounds).

They fashioned a sleeping bag with insulation from the rear of the fuselage, electrical wire and the waterproof fabric that covered the plane's air conditioning unit.

[24][23] Parrado described in his book, Miracle in the Andes: 72 Days on the Mountain and My Long Trek Home, how they came up with the idea of making a sleeping bag: The second challenge would be to protect ourselves from exposure, especially after sundown.

Believing he would see the green valleys of Chile to the west, he was stunned when he was faced with seemingly unending snow-capped mountain peaks extending in every direction.

[23][32] During the trip Catalán ran into another arriero on the south bank of the Azufre river and asked him to ride towards the survivors and take them to the Los Maitenes village.

[38][39][23] When the news broke out that survivors had emerged from the crash of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, the story of their 72-day ordeal drew international attention.

[citation needed] However, according to Juan Ulloa, an Argentinian guide who hiked Canessa and Parrado's route multiple times, they ultimately made the right choice despite the longer distance.

Unable to obtain official permission from Argentine authorities to retrieve his son's body, Echavarren hired guides and mounted an illegal expedition of his own.

[3] The survivors' courage under life-threatening conditions has been described as "a beacon of hope to [their] generation, showing what can be accomplished with persistence and determination in the face of unsurpassable odds when we set our minds to attain a common goal".

Canessa also co-authored a book titled I Had to Survive; How a Plane Crash in the Andes Inspired My Calling to Save Lives, which was published by Simon and Schuster in 2017.