British Military Administration (Malaya)

The administration had the dual function of maintaining basic subsistence during the period of reoccupation, and also of imposing the state structure upon which post-war imperial power would rest.

The first phase was to be a Military Administration that returned stability followed by a Malay Union that would bring together all the states under a single government to secure Britain's possessions in Malaya.

During the war the Allies dropped propaganda leaflets stressing that the Japanese issued money would be valueless when Japan surrendered.

This was followed by the signing of the Malaya surrender document at Kuala Lumpur by Lieutenant-General Teizo Ishiguro, commander of the 29th Army; with Major-General Naoichi Kawahara, Chief of Staff; and Colonel Oguri as witnesses.

Another surrender ceremony was held in Kuala Lumpur on 22 February 1946 for General Seishirō Itagaki, the Commander of the 7th Area Army.

The BMA assumed full judicial, legislative, executive and administrative powers and responsibilities and conclusive jurisdiction over all persons and property throughout Malaya including Singapore.

[14] Given the military nature of the administration, the official power of some of the pre-war civilian governments' entities were suspended, including the rights of the Malay sultanate rulers.

Colonel John G. Adams of the London Irish Rifles (previously injured in action during the Sicilian campaign on the Catania plains) was selected as the President of the Superior Court in 1945.

These included the detention and disarming of the Japanese military, the identification and trial of war criminals, the release and repatriation of prisoners of war, the repair of key infrastructure, enabling the re-establishment of key industries, the disarming and repatriation of guerrilla armies including the MPAJA, the re-establishment of the rule of law, and the distribution of food and medical supplies.

[19] Further complicating matters pre-War British colonial administrations had adhered to a strict code of behaviour, and thus corruption had been virtually absent.

[15]: 13 Under the Japanese, however, bribery, smuggling, extortion, black market dealings, and other unsavory habits had become a way of life and were much too ingrained to be changed without a strenuous effort once the British returned.

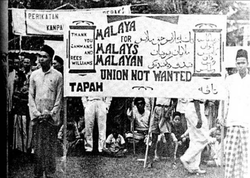

The Japanese had also used the slogan Malaya for the Malays as part of their war time propaganda raising with it a desire for independence from Colonial government.

[20] One aspect the military government might have been expected to be most successful- that of ensuring personal security- they were found wanting..[citation needed] Firstly, the BMA were incapable of curbing what was widely referred to as 'gangsterism'.

[citation needed] Through the personnel make up and economic policies of the BMA, one may see they were in no good position of winning back the hearts and minds of the Malayan peoples.

[citation needed] The greatest initial challenge of authority for the British Military Administration was its capacity to re-introduce and re-enforce order in trade and employment in the aftermath of Japanese surrender and departure.

[11] In addition, within a few days after the British arrived in Malaya, it was announced that the Japanese currency, or 'Banana money' as it was called, was 'worth no more than the paper on which it is printed'.

A plan was formulated in which the Federated and Unfederated Malay States, along with the Straits Settlements (excluding Singapore) were to be merged into a single entity called the Malayan Union.

Included in the proposed union was the removal of political power from the sultans and granting of citizenship to non-Malays who had been resident in Malaya for at least 10 out of 15 years prior to 15 February 1942.

Sir Harold MacMichael was empowered to sign revised treaties with the Malay sultans to enable the Union to proceed.

The Sultan quickly consented to MacMichael's proposal scheme, which was motivated by his strong desire to visit England at the end of the year.

Many Malay rulers expressed strong reluctance in signing the treaties with MacMichael, partly because they feared losing their royal status and the prospect of their states falling into Thai political influence.

The Colonial office suddenly found that it had forgotten its own pre-war advice on the need to maintain the Malay populations position of privilege.

[26] Malay reaction was swift with seven political dissidents led by Awang bin Hassan organised a rally on 1 February 1946 to protest against the Sultan of Johore's decision to sign the treaties, and Onn Jaafar, who was then serving as a district officer in Batu Pahat, was invited to attend the rally.

The British capitulated and agreed that while the Malayan Union still commenced on 1 April 1946 negotiations began in July 1946 for its replacement.