British entry into World War I

The official explanation focused on protecting Belgium as a neutral country; the main reason, however, was to prevent a French defeat that would have left Germany in control of Western Europe.

For much of the 19th century, Britain pursued a foreign policy later known as splendid isolation, which sought to maintain the balance of power in Europe without formal alliances.

[2] The 1911 Agadir Crisis encouraged secret military negotiations between France and Britain in the case of war with the German Empire.

It was in essence not a consequence of the disputes over economic trade imperialism, the Baghdad Railway, the confrontations in Eastern Europe, highly-charged political rhetoric, or domestic pressure groups.

[6][7] As Germany and Russia became the central players in the crisis (respectively backing Austria-Hungary and Serbia), British leaders increasingly had a sense of commitment to defending France.

First, if Germany again conquered France, as had happened in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, it would become a major threat to British economic, political and cultural interests.

It denounced a "conspiracy to drag us into a war against England’s interests", arguing that it would amount to a "crime against Europe", and warning that it would "throw away the accumulated progress of half a century".

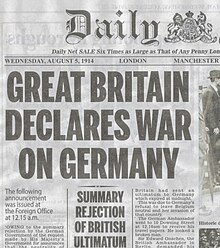

[13] The politician David Lloyd George told Scott on Tuesday 4 August 1914, "Up until last Sunday only two members of the Cabinet had been in favour of our intervention in the war, but the violation of Belgian territory had completely altered the situation".

[17] The German invasion of Belgium was such an outrageous violation of international rights that the Liberal Party agreed for war on 4 August.

Unless the Liberal government acted decisively against the German invasion of France, its top leaders including Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, Foreign Minister Edward Grey, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill and others would resign, leading to a risk that the much more pro-war Conservative Party might form a government.

Both sides in Ireland had smuggled in weapons, set up militias with tens of thousands of volunteers, were drilling, and were ready to fight a civil war.

The British Army itself was paralyzed: during the Curragh Incident officers threatened to resign or accept dismissal rather than obey orders to deploy into Ulster.