British foreign policy in the Middle East

These included maintaining access to British India, blocking Russian or French threats to that access, protecting the Suez Canal, supporting the declining Ottoman Empire against Russian threats, guaranteeing an oil supply after 1900 from Middle East fields, protecting Egypt and other possessions in the Middle East, and enforcing Britain's naval role in the Mediterranean.

The timeframe of major concern stretches from the 1770s when the Russian Empire began to dominate the Black Sea, down to the Suez Crisis of the mid-20th century and involvement in the Iraq War in the early 21st.

The Greeks had strong intellectual and business communities which employed propaganda echoing the French Revolution that appealed to the romanticism of Western Europe.

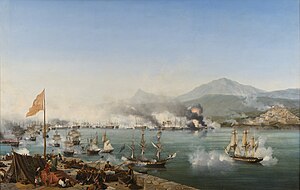

[9] The Powers agreed, by the Treaty of London (1827), to force the Ottoman government to grant the Greeks autonomy within the empire and despatched naval squadrons to Greece to enforce their policy.

Tsar Nicholas I visited London in person and consulted with Foreign Secretary Lord Aberdeen regarding what would happen if the Ottoman Empire collapsed and had to be split up.

When Aberdeen became Prime Minister in 1852, the tsar mistakenly believed he had British approval for action against Turkey and was shocked when Britain declared war.

He defined the popular imagination which saw the war against Russia is a commitment to British principles, notably the defense of liberty, civilization, free trade; and championing the underdog.

The war's great hero was Florence Nightingale, the nurse who brought scientific management and expertise to heal the horrible sufferings of the tens of thousands of sick and dying British soldiers.

[19] according to historian R. B. McCallum the Crimean War: As owners of the Suez Canal, both British and French governments had strong interests in the stability of Egypt.

Combined with the complete turmoil in Egyptian finances, the threat to the Suez Canal, and embarrassment to British prestige if it could not handle a revolt, London found the situation intolerable and decided to end it by force.

On 11 July 1882, Prime Minister William E. Gladstone ordered the bombardment of Alexandria which launched the short decisive Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882.

They argue that the Liberals had no long-term plan for imperialism but acted out of necessity to protect the Suez Canal amid a nationalist revolt and the threat to law and order in Egypt.

Critics like Cain and Hopkins emphasize the need to protect British financial investments in Egypt, downplaying the risks to the Suez Canal.

[29] : 373–374 He argues that Gladstone's cabinet was motivated by the need to protect British bondholders' investments in Egypt and to gain domestic political popularity.

[29]: 382 Hopkins cites a letter from Edward Malet, the British consul general in Egypt at the time, to a member of the Gladstone Cabinet offering his congratulations on the invasion: "You have fought the battle of all Christendom and history will acknowledge it.

Instead, the primary motivation was the vindication of British prestige in both Europe and especially in India by suppressing the threat to "civilised" order posed by the Urabist revolt.

[32] Since the late 1870s Gladstone had moved Britain into playing a leading role in denouncing the harsh policies and atrocities and mobilizing world opinion.

The shock of Napoleon's 1798 expedition to Egypt led London to significantly strengthen its ties in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, pushing out the French and Dutch rivals, and upgrading the East India Company operations to diplomatic status.

The main advantage of oil was that a warship could easily carry fuel for long voyages without having to make repeated stops at coaling stations.

In response the East India Company (EIC) negotiated an agreement with Aden’s sultan that provided rights to the deepwater harbor on Arabia's southern coast including a strategically important coaling station.

The National Liberation Front quickly took power and announced the creation of a communist People’s Republic of South Yemen, deposing the traditional leaders in the sheikhdoms and sultanates.

The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after the war led to the domination of the Middle East by Western powers such as Britain and France, and saw the creation of the modern Arab world and the Republic of Turkey.

Resistance to the influence of these powers came from the Turkish National Movement but did not become widespread in the other post-Ottoman states until the period of rapid decolonization after World War II.

The sometimes-violent creation of protectorates in Iraq and Palestine, and the proposed division of Syria along communal lines, is thought to have been a part of the larger strategy of ensuring tension in the Middle East, thus necessitating the role of Western colonial powers (at that time Britain, France and Italy) as peace brokers and arms suppliers.

Under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne Mosul fell under the British Mandate of Mesopotamia, but the new Turkish republic claimed the province as part of its historic heartland.

Lastly, the British promised via the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence that the Hashemite family would have lordship over most land in the region in return for their support in the Great Arab Revolt.

Herbert Samuel, a former Postmaster General in the British cabinet who was instrumental in drafting the Balfour Declaration, was appointed the first High Commissioner in Palestine.

Experts from India designed the new system, which favoured direct rule by British appointees, and demonstrated distrust of the aptitude of local Arabs for self-government.

The Suez Crisis of 1956 was a major disaster for British (and French) foreign policy and left Britain a minor player in the Middle East because of very strong opposition from the United States.

U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower had strongly warned Britain not to invade; he threatened serious damage to the British financial system by selling the US government's pound sterling bonds.