History of Hungary before the Hungarian conquest

The first known traces belong to the Homo heidelbergensis, with scarce or nonexistent evidence[1] of human presence until the Neanderthals around 100,000 years ago.

[2] The rest of the Stone Age is marked by minimal or not-yet-processed archeological evidence, with the exception of the Linear Pottery culture—the "garden type civilization"[3] that introduced agriculture to the Carpathian Basin.

The major improvement was obviously metalworking, but the Baden culture also brought about cremation and even long-distance trade with remote areas such as the Baltic or Iran.

The Roman era began with several attacks between 156 and 70 BC, but their gradual conquest was interrupted by the Dacian king Burebista, whose kingdom stretched as far as today's Slovakia at its greatest extent.

Numerous Germanic tribes lived alongside them such as the Goths, Marcomanni, Quadi or Gepidi, the last of which stayed the longest and whose peoples incorporated into the Hunnic Empire.

The oldest archaeological site which yielded evidence of human presence—human bones, pebble tools and kitchen refuse—in the Carpathian Basin was excavated at Vértesszőlős in Transdanubia in the 1960s.

[5][6] The Middle Pleistocene site was situated in calcareous tuff basins with a diameter of 3–6 meters (9.8–19.7 ft) that the nearby warm springs had formed.

[12] A flat oval object made from mammoth tooth lamella, similar to the Indigenous Australians' ritual tjurunga, was found at the site.

[2] According to a scholarly view, a local archaeological culture—the "Szeleta culture"—can be distinguished, which represents a transition between the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic and was featured by leaf-shaped spearheads from around 32,000 BC.

[8][2][15] However, the existence of a distinct archaeological culture is not unanimously accepted by specialists, because most prehistoric tools from the eponymous Szeleta Cave (in the eastern side of the Bükk) are similar to those found in the Upper Palaeolithic sites of Central Europe.

[15] Attracted by the rich fauna of the lowlands in the centre of the Carpathian Basin, groups of "Gravettian" hunters penetrated into the territory from the west about 27,000 years ago.

[18] A pendant made of wolf tooth, a pair of red deer teeth and similar finds suggest that these hunters wore ornaments.

Similar cultures are known further east in Central Europe, parts of Britain and west across Spain, extending possibly to the nowadays North-Western Hungary.

It originates in the spread of the Neolithic package of peoples and technological innovations including farming and ceramics from Anatolia to the area of Sesklo.

In Hungarian and Slovakian sites, cremated human remains were often placed in anthropomorphic urns, whereas in Nitriansky Hrádok, a mass grave has been found.

The only known cemetery with individual graves was found in an early Baden ("Boleráz phase") site is Pilismarót, in Komárom-Esztergom County, which also contained a few examples of goods possibly exported from the Stroke-ornamented ware culture (centred in what is now Poland).

[26] The people of the Hallstatt culture took over the former population's fortifications (e.g., in Velem, Celldömölk, Tihany) but they also built new ones enclosed with earthworks (e.g., in Sopron).

[26] Following 279 BC, the Scordisci (a Celtic tribe), who had been defeated at Delphi, settled at the confluence of the rivers Sava and Danube and they extended their rule over the southern parts of Transdanubia.

[26][27] In 119 BC, they marched against Siscia (today Sisak in Croatia) and strengthened their rule over the future Illyricum province south of the Carpathian Basin.

[27][29] Burebista's victory over the Celts led not only to the breakup of their tribal alliance, but also to the establishment of Dacian settlements in the southern parts of today's Slovakia.

The territory between the Danube and the Tisza was inhabited by the Sarmatian Iazyges between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, or even earlier (earliest remains have been dated to 80 BC).

Many of the important cities of today's Hungary were founded during this period, such as Aquincum (Budapest), Sopianae (Pécs), Arrabona (Győr), Solva (Esztergom), Savaria (Szombathely) and Scarbantia (Sopron).

The Pannonian provinces suffered from the Migration Period from 379 onwards, the settlement of the Goth-Alan-Hun ally caused repeated serious crises and devastations, the contemporaries described it as a state of siege, Pannonia became an invasion corridor both in the north and in the south.

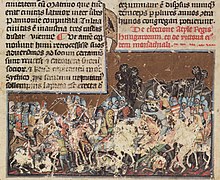

And the Huns wanted to die rather than retreat in the battle, according to Scythian custom they made a terrifying noise, they beat their drums and used every weapon against the enemy, but most of all their innumerable number of arrows.

The morning began, and in a fierce battle which lasted until nine o'clock, the Roman army was defeated and put to flight with enormous loss.Bishop Amantius fled around 400 to Aquileia.

According to András Mócsy, it is not possible to prove whether the reconstruction of a church is to be attributed to barbarians or to remained Romans at the majority of places.

There are examples of sporadic Romans who had stayed behind in the 5th century, Saint Anthony the Hermit was born in Pannonia Valeria and as an orphaned child he was sent to his uncle, Constantius, the Bishop of Lorsch in today Germany.

[31] Later, Christian barbarians who migrated to the northern part of Lake Balaton established the Keszthely Culture, which disappeared by the middle of the 7th century.

The nomadic Avars arrived from Asia in the 560s, utterly destroyed the Gepidi in the east, drove away the Lombards in the west, and subjugated the Slavs, partly assimilating them.

This empire was destroyed around 800 by Frankish and Bulgar attacks, and above all by internal feuds, however Avar population remained in numbers until the arrival of Árpád's Magyars.