First Bulgarian Empire

[24] The reign of Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565) saw temporary recovery of control and reconstruction of a number of fortresses, but after his death the empire was unable to face the threat of the Slavs due to the significant reduction of revenue and manpower.

[31] As the wars with Persia persisted, the 610s and 620s saw a new and even larger migration wave with the Slavs penetrating further south into the Balkans, reaching Thessaly, Thrace and Peloponnese and raiding some islands in the Aegean Sea.

[49] In the 670s they crossed the Danube into Scythia Minor, nominally a Byzantine province, whose steppe grasslands and pastures were important for the large herd stocks of the Bulgars in addition to the grazing grounds to the west of the Dniester River already under their control.

[53] In 681, the Byzantines were compelled to sign a humiliating peace treaty, forcing them to acknowledge Bulgaria as an independent state, to cede the territories to the north of the Balkan Mountains and to pay an annual tribute.

[49] The Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor wrote of the treaty: ... the Emperor [Constantine IV] signed peace with them [the Bulgars], and agreed to pay them tribute for shame of the Romans and for our many sins.

[67] Skirmishes continued until 716 when Khan Tervel signed an important agreement with Byzantium that defined the borders and the Byzantine tribute, regulated trade relations and provided for the exchange of prisoners and fugitives.

[81] During the reign of Krum (r. 803–814) Bulgaria doubled in size and expanded to the south, west and north, occupying the vast lands along the middle Danube and Transylvania, becoming European medieval great power[11] during the 9th and 10th century along with the Byzantine and Frankish Empires.

[86][87] Krum took the initiative and in 812 moved the war towards Thrace, capturing the key Black Sea port of Messembria and defeating the Byzantines once more at Versinikia in 813 before proposing a generous peace settlement.

[89] Khan Krum implemented legal reforms and issued the first known written law code of Bulgaria that established equal rules for all peoples living within the country's boundaries, intending to reduce poverty and to strengthen the social ties in his vastly enlarged state.

[92][93] Krum's successor Khan Omurtag (r. 814–831) concluded a 30-year peace treaty with the Byzantines establishing the border along the Erkesia trench between Debeltos on the Black Sea and the valley of the Maritsa River at Kalugerovo, thus allowing both countries to restore their economies and finance after the bloody conflicts in the first decade of the century.

[98] Extensive building was undertaken in the capital Pliska, including the construction of a magnificent palace, pagan temples, ruler's residence, fortress, citadel, water-main, and bath, mainly from stone and brick.

[113][114] In 894 the Byzantines moved the Bulgarian market from Constantinople to Thessaloniki, affecting the commercial interests of Bulgaria and the principle of Byzantine–Bulgarian trade, regulated under the Treaty of 716 and later agreements on the most favoured nation basis.

[126] However, the military and ideological initiative was held by Simeon I, who was seeking casus belli to fulfil his ambition to be recognized as Emperor (in Bulgarian, Tsar) and to conquer Constantinople, creating a joint Bulgarian–Roman state.

[137][138] Simeon I was aware that he needed naval support to conquer Constantinople and in 922 sent envoys to the Fatimid caliph Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi Billah in Mahdia to negotiate the assistance of the powerful Arab navy.

The growing insecurity, as well as expanding influence of the landed nobility and the higher clergy at the expense of the personal privileges of the peasantry, led to the emergence of Bogomilism, a dualistic heretic sect that in the subsequent centuries spread to the Byzantine Empire, northern Italy and southern France (cf.

When in 976 the rightful heir to the throne, Boris II's brother Roman (r. 971–997), escaped from captivity in Constantinople, he was recognized as Emperor by Samuel,[160][c] who remained the chief commander of the Bulgarian army.

Peace was impossible; as a result of the symbolic ending of the Bulgarian Empire following Boris II's abdication, Roman, and later Samuel, were seen as rebels and the Byzantine Emperor was bound to enforce the imperial sovereignty over them.

[168] In 1001 they seized Pliska and Preslav in the east; in 1003 a major offensive along the Danube resulted in the fall of Vidin after an eight-month siege; and in 1004 Basil II defeated Samuel in the battle of Skopje and took possession of the city.

Some 14,000 Bulgarians were captured; it is said that 99 out of every 100 men were blinded, with the remaining hundredth man left with one eye so as to lead his compatriots home, earning Basil II the moniker "Bulgaroktonos", the Bulgar Killer.

[194] The presence of two separate classes of nobility is further confirmed in the Responsa Nicolai ad consulta Bulgarorum (Responses of Pope Nicholas I to the Questions of the Bulgarians), where Boris I wrote about primates and mediocres seu minores.

[196] The beginning of the 9th century was marked with a process of incorporation of both Slavs and Byzantine Greeks in the ranks of the Bulgarian nobility and privileged classes, which increased the power of the monarch that had been previously curtailed by the leading Bulgar aristocratic families.

[207] The first known written Bulgarian law code was issued by Khan Krum at a People's Council in the very beginning of the 9th century but the text has not survived in its entirety and only certain items have been preserved in the 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia Suda.

[212] Eventually, the Законъ соудный людьмъ (Zakon sudnyi ljud'm, Court Law for the People), was compiled, based heavily on the Byzantine Ecloga and Nomocanon, but adapted to Bulgarian conditions and valid for the whole population of the country.

[221] In 918 the Bulgarians took the capital of the Byzantine theme Hellas Thebes without bloodshed after sending five men with axes into the city, who eliminated the guards, broke the hinges of the gates, and opened them to the main forces.

The Bulgarians employed the services of Byzantine and Arab captives and fugitives to produce siege equipment, such as the engineer Eumathius, who sought refuge with Khan Krum after the capture of Serdica in 809.

[115] The relevance of international trade for Bulgaria was evident, as the country was willing to go to war with the Byzantine Empire when, in 894, the latter moved the market of the Bulgarian traders from Constantinople to Thessaloniki, where they had to pay higher taxes and did not have direct access to goods from the east.

[247] Perun was the only god mentioned (though not by name) by the first authoritative reference to the Slavic mythology in written history, the 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius, who described the Slavs that settled south of the Danube.

[191] Since the Byzantines were reluctant to grant any concessions Boris I took advantage on the ongoing rivalry between the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Papacy in Rome in order to prevent either of them from exerting religious influence on his lands.

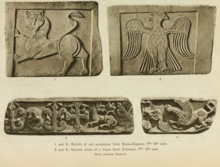

Many monuments of that period have been found around Madara, Shumen, Novi Pazar, the village of Han Krum in north-eastern Bulgaria, and in the territory of modern Romania, where Romanian archaeologists called it the "Dridu culture".

[297] The fortress of Slon, an important juncture that connected the salt mines of Transylvania with the lands to the south of the Danube, and constructed in the same manner, was located further north, on the southern slopes of the Carpathian Mountains.