Cold seep

Cold seeps develop unique topography over time, where reactions between methane and seawater create carbonate rock formations and reefs.

[4] They sustain different geochemical and microbial processes that are reflected in a complex mosaic of habitats inhabited by a mixture of specialist (heterotrophic and symbiont-associated) and background fauna.

[3] Mostly composed of species in the genus Bathymodiolus, these mussels do not directly consume food;[3] Instead, they are nourished by symbiotic bacteria that also produce energy from methane, similar to their relatives that form mats.

[3] Chemosynthetic bivalves are prominent constituents of the fauna of cold seeps and are represented in that setting by five families: Solemyidae, Lucinidae, Vesicomyidae, Thyasiridae, and Mytilidae.

Understanding how efficient the benthic filter is can help predict how much methane escapes the seafloor at cold seeps and enters the water column and eventually the atmosphere.

[2] Both systems share common characteristics such as the presence of reduced chemical compounds (H2S and hydrocarbonates), local hypoxia or even anoxia, a high abundance and metabolic activity of bacterial populations, and the production of autochthonous, organic material by chemoautotrophic bacteria.

[2] Community-level comparisons reveal that vent, seep, and organic-fall macrofauna are very distinct in terms of composition at the family level, although they share many dominant taxa among highly sulphidic habitats.

[4] Cold seeps are common along continental margins in areas of high primary productivity and tectonic activity, where crustal deformation and compaction drive emissions of methane-rich fluid.

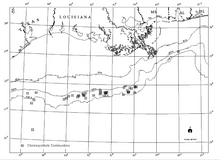

Bottom photography as part of this project obtained images from the end of a film roll of a deep-sea camera sled (processed on board the vessel November 14, 1984) that resulted in clear images of vesicomyid clam chemosynthetic communities (Rossman et al., 1987[25]) coincidentally in the same manner as the first documentation of chemosynthetic communities at the Galapagos Rift investigating hot water plumes by camera sled in the Pacific in 1976 (Lonsdale 1977[26]).

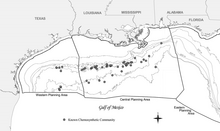

This site represents the first eyes-on human observations of chemosynthetic communities in the northern Gulf of Mexico and is characterized by dense tubeworm and mussel accumulations, as well as exposed carbonate outcrops with numerous gorgonian and Lophelia coral colonies.

[21] In the upper slope environment, the hard substrates resulting from carbonate precipitation can have associated communities of non-chemosynthetic animals, including a variety of sessile cnidarians such as corals and sea anemones.

[21] The widespread nature of Gulf of Mexico chemosynthetic communities was first documented during contracted investigations by the Geological and Environmental Research Group (GERG) of Texas A&M University for the Offshore Operators Committee.

[37][21] It is a surprisingly large and dense community of chemosynthetic tube worms and mussels at a site of natural petroleum and gas seepage over a salt diapir in Green Canyon Block 185.

Although not as destructive as the volcanism at vent sites of the mid-ocean ridges, the dynamics of shallow hydrate formation and movement will clearly affect sessile animals that form part of the seepage barrier.

There is potential of a catastrophic event where an entire layer of shallow hydrate could break free of the bottom and considerably affect local communities of chemosynthetic fauna.

Powell also found that both the composition of species and trophic tiering of hydrocarbon seep communities tend to be fairly constant across time, with temporal variations only in numerical abundance.

No mass die-offs or large-scale shifts in faunal composition have been observed (with the exception of collections for scientific purposes) over the 19-year history of research at this site.

[21] Individual lamellibrachid tube worms, the longer of two taxa found at seeps, can reach lengths of 3 m (10 ft) and live hundreds of years (Fisher et al., 1997; Bergquist et al., 2000).

One recent discovery indicates that the spawning of female Lamellibrachia appears to have produced a unique association with the large bivalve Acesta bullisi, which lives permanently attached to the anterior tube opening of the tubeworm, and feeds on the periodic egg release (Järnegren et al., 2005).

It is clear that seep systems do interact with the background fauna, but conflicting evidence remains as to what degree outright predation on some specific community components such as tubeworms occurs (MacDonald, 2002).

In fact, seep-associated consumers such as galatheid crabs and nerite gastropods had isotopic signatures, indicating that their diets were a mixture of seep and background production.

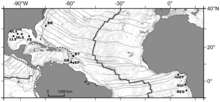

The Bathymodiolus childressi complex is also widely distributed along the Atlantic Equatorial Belt from the Gulf of Mexico across to the Nigerian Margin, although not on the Regab or Blake Ridge sites.

In the southeastern Mediterranean, communities of polychaetes and bivalves were also found associated with cold seeps and carbonates near Egypt and the Gaza Strip at depths of 500–800 m, but no living fauna was collected.

[47] Members of cold seep communities are similar to other regions in terms of family or genus, such as Polycheata, Lamellibrachia, Bivalavia, Solemyidae, Bathymodiolus in Mytilidae, Thyasiridae, Calyptogena in Vesicomyidae, and so forth.

[51][52] Off the mainland coast of New Zealand, shelf-edge instability is enhanced in some locations by cold seeps of methane-rich fluids that likewise support chemosynthetic faunas and carbonate concretions.

[58] Furthermore, in these soft reduced sediments below the oxygen minimum zone off the Chilean margin, a diverse microbial community composed by a variety of large prokaryotes (mainly large multi-cellular filamentous "mega bacteria" of the genera Thioploca and Beggiatoa, and of "macrobacteria" including a diversity of phenotypes), protists (ciliates, flagellates, and foraminifers), as well as small metazoans (mostly nematodes and polychaetes) has been found.

[16] The relatively few investigations to the Antarctic deep sea have shown the presence of deep-water habitats, including hydrothermal vents, cold seeps, and mud volcanoes.

Seafloor litter alters the habitat by providing hard substrate where none was available before or by overlying the sediment, thereby inhibiting gas exchange and interfering with organisms on the bottom of the sea.

Chemical contaminants such as persistent organic pollutants, toxic metals (e.g., Hg, Cd, Pb, Ni), radioactive compounds, pesticides, herbicides, and pharmaceuticals are also accumulating in deep-sea sediments.

[77] Topography (such as canyons) and hydrography (such as cascading events) play a major role in the transportation and accumulation of these chemicals from the coast and shelf to the deep basins, affecting the local fauna.

BR – Blake Ridge diapir

BT – Barbados trench

OR – Orenoque sectors

EP – El Pilar sector

NIG – Nigerian slope

GUI – Guiness area

REG – Regab pockmark.