Buckminsterfullerene

It has a cage-like fused-ring structure (truncated icosahedron) made of twenty hexagons and twelve pentagons, and resembles a soccer ball.

[11][12][13][14] It was first generated in 1984 by Eric Rohlfing, Donald Cox, and Andrew Kaldor[14][15] using a laser to vaporize carbon in a supersonic helium beam, although the group did not realize that buckminsterfullerene had been produced.

In 1985 their work was repeated by Harold Kroto, James R. Heath, Sean C. O'Brien, Robert Curl, and Richard Smalley at Rice University, who recognized the structure of C60 as buckminsterfullerene.

A solid rotating graphite disk was used as the surface from which carbon was vaporized using a laser beam creating hot plasma that was then passed through a stream of high-density helium gas.

[11] Kroto, Curl, and Smalley were awarded the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their roles in the discovery of buckminsterfullerene and the related class of molecules, the fullerenes.

[11] In 1989 physicists Wolfgang Krätschmer, Konstantinos Fostiropoulos, and Donald R. Huffman observed unusual optical absorptions in thin films of carbon dust (soot).

Among other features, the IR spectra of the soot showed four discrete bands in close agreement to those proposed for C60.

[21][22] Another paper on the characterization and verification of the molecular structure followed on in the same year (1990) from their thin film experiments, and detailed also the extraction of an evaporable as well as benzene-soluble material from the arc-generated soot.

The discovery of practical routes to C60 led to the exploration of a new field of chemistry involving the study of fullerenes.

The discoverers of the allotrope named the newfound molecule after American architect R. Buckminster Fuller, who designed many geodesic dome structures that look similar to C60 and who had died in 1983, the year before discovery.

The reason for this color change is the relatively narrow energy width of the band of molecular levels responsible for green light absorption by individual C60 molecules.

Upon drying, intermolecular interaction results in the overlap and broadening of the energy bands, thereby eliminating the blue light transmittance and causing the purple to brown color change.

This change is associated with a first-order phase transition to an fcc structure and a small, yet abrupt increase in the lattice constant from 1.411 to 1.4154 nm.

[40] It is an n-type semiconductor with a low activation energy of 0.1–0.3 eV; this conductivity is attributed to intrinsic or oxygen-related defects.

[41] Fcc C60 contains voids at its octahedral and tetrahedral sites which are sufficiently large (0.6 and 0.2 nm respectively) to accommodate impurity atoms.

C60 tends to avoid having double bonds in the pentagonal rings, which makes electron delocalization poor, and results in C60 not being "superaromatic".

For example, C60 reacts with lithium in liquid ammonia, followed by tert-butanol to give a mixture of polyhydrofullerenes such as C60H18, C60H32, C60H36, with C60H32 being the dominating product.

Under high pressure and temperature, repeated [2+2] cycloaddition between C60 results in polymerized fullerene chains and networks.

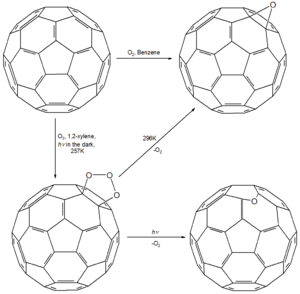

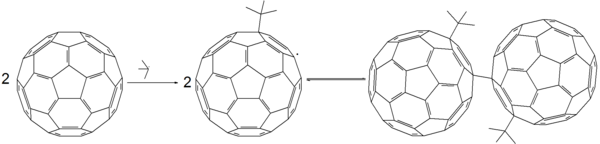

When tert-butyl halide is photolyzed and allowed to react with C60, a reversible inter-cage C–C bond is formed:[44] Cyclopropanation (the Bingel reaction) is another common method for functionalizing C60.

[44] Phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester derivative prepared through cyclopropanation has been studied for use in organic solar cells.

This small gap suggests that reduction of C60 should occur at mild potentials leading to fulleride anions, [C60]n− (n = 1–6).

The midpoint potentials of 1-electron reduction of buckminsterfullerene and its anions is given in the table below: C60 forms a variety of charge-transfer complexes, for example with tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene: This salt exhibits ferromagnetism at 16 K. C60 oxidizes with difficulty.

These endohedral fullerenes are usually synthesized by doping in the metal atoms in an arc reactor or by laser evaporation.

[50][51] So the management of C60 products for human ingestion requires cautionary measures[51] such as: elaboration in very dark environments, encasing into bottles of great opacity, and storing in dark places, and others like consumption under low light conditions and using labels to warn about the problems with light.

Solutions of C60 dissolved in olive oil or water, as long as they are preserved from light, have been found nontoxic to rodents.

[52] Otherwise, a study found that C60 remains in the body for a longer time than usual, especially in the liver, where it tends to be accumulated, and therefore has the potential to induce detrimental health effects.

A later research confirmed that exposure to light degrades solutions of C60 in oil, making it toxic and leading to a "massive" increase of the risk of developing cancer (tumors) after its consumption.

60 solution, showing diminished absorption for the blue (~450 nm) and red (~700 nm) light that results in the purple color.

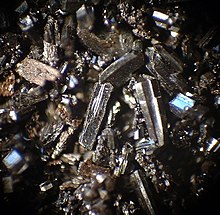

60 in crystal.