Buddhist art

Artists were reluctant to depict the Buddha anthropomorphically, and developed sophisticated aniconic symbols to avoid doing so (even in narrative scenes where other human figures would appear).

This tendency remained as late as the 2nd century CE in the southern parts of India, in the art of the Amaravati School (see: Mara's assault on the Buddha).

The three main centers of creation have been identified as Gandhara in today's North West Frontier Province, in Pakistan, Amaravati and the region of Mathura, in central northern India.

Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka (r. 268–232 BCE), who formed the largest Empire in the Indian subcontinent, converted to Buddhism following the Kalinga War.

Figures were much larger than any known from India previously, and also more naturalistic, and new details included wavy hair, drapery covering both shoulders, shoes and sandals, and acanthus leaf ornament.

It is still a matter of debate whether the anthropomorphic representations of Buddha was essentially a result of a local evolution of Buddhist art at Mathura, or a consequence of Greek cultural influence in Gandhara through the Greco-Buddhist syncretism.

[citation needed] Remains of early Buddhist painting in India are vanishingly rare, with the later phases of the Ajanta Caves giving the great majority of surviving work, created over a relatively short up to about 480 CE.

The pink sandstone sculptures of Mathura evolved during the Gupta period (4th to 6th century CE) to reach a very high fineness of execution and delicacy in the modeling.

These areas, helped by their location, were in greater contact with Tibet and China – for example the art and traditions of Ladakh bear the stamp of Tibetan and Chinese influence.

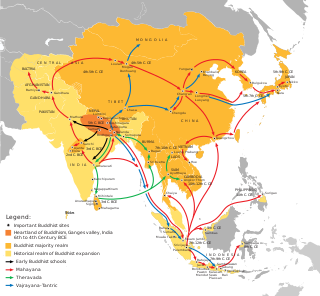

Central Asian missionary efforts along the Silk Road were accompanied by a flux of artistic influences, visible in the development of Serindian art from the 2nd through the 11th century in the Tarim Basin, modern Xinjiang.

Other sculptures, in stucco, schist or clay, display very strong blending of Indian post-Gupta mannerism and Classical influence, Hellenistic or possibly even Greco-Roman.

The multiple conflicts since the 1980s also have led to a systematic pillage of archaeological sites apparently in the hope of reselling in the international market what artifacts could be found.

[27] The introduction of Buddhism stimulated the need for artisans to create images for veneration, architects for temples, and the literate for the Buddhist sutras and transformed Korean civilization.

Baekje architects were famed for their skill and were instrumental in building the massive nine-story pagoda at Hwangnyongsa and early Buddhist temples in Yamato Japan such as Hōkō-ji (Asuka-dera) and Hōryū-ji.

Particularly, the semi-seated Maitreya form was adapted into a highly developed Korean style which was transmitted to Japan as evidenced by the Koryu-ji Miroku Bosatsu and the Chugu-ji Siddhartha statues.

Although many historians portray Korea as a mere transmitter of Buddhism, the Three Kingdoms, and particularly Baekje, were instrumental as active agents in the introduction and formation of a Buddhist tradition in Japan in 538 or 552.

Tang China was the cross roads of East, Central, and South Asia and so the Buddhist art of this time period exhibit the so-called international style.

[38][39] From the 12th and 13th, a further development was Zen art, and it faces golden days in Muromachi period, following the introduction of the faith by Dogen and Eisai upon their return from China.

Zen art is mainly characterized by original paintings (such as sumi-e) and poetry (especially haikus), striving to express the true essence of the world through impressionistic and unadorned "non-dualistic" representations.

From that time, through trade connections, commercial settlements, and even political interventions, India started to strongly influence Southeast Asian countries.

This period marked the renaissance of Buddhist art in Java, as numerous exquisite monuments were built, including Kalasan, Manjusrigrha, Mendut and Borobudur stone mandala.

The Theravada Buddhism of the Pali canon was introduced to the region around the 13th century from Sri Lanka, and was adopted by the newly founded ethnic Thai kingdom of Sukhothai.

Since in Theravada Buddhism of the period, Monasteries typically were the central places for the laity of the towns to receive instruction and have disputes arbitrated by the monks, the construction of temple complexes plays a particularly important role in the artistic expression of Southeast Asia from that time.

From the 14th century, the main factor was the spread of Islam to the maritime areas of Southeast Asia, overrunning Malaysia, Indonesia, and most of the islands as far as the Southern Philippines.

According to tradition, Buddhism was introduced in Sri Lanka in the 3rd century BCE by Indian missionaries under the guidance of Thera Mahinda, the son of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka.

In this style, the Buddha has large protruding ears, exaggerated eyebrows that curve upward, half-closed eyes, thin lips and a hair bun that is pointed at the top, usually depicted in the bhumisparsa mudra.

[44] There was a marked departure from the Innwa style, and the Buddha's face is much more natural, fleshy, with naturally-slanted eyebrows, slightly slanted eyes, thicker lips, and a round hair bun at the top.

Up to the end of that period, Buddhist art is characterized by a clear fluidness in the expression, and the subject matter is characteristic of the Mahayana pantheon with multiple creations of Bodhisattvas.

The islands of Sumatra and Java in western Indonesia were the seat of the empire of Sri Vijaya (8th–13th century), which came to dominate most of the area around the Southeast Asian peninsula through maritime power.

The most beautiful example of classical Javanese Buddhist art is the serene and delicate statue of Prajnaparamita of Java (the collection of National Museum Jakarta) the goddess of transcendental wisdom from Singhasari kingdom.