Rock relief

Stylistically they normally relate to other types of sculpture from the culture and period concerned, and except for Hittite and Persian examples they are generally discussed as part of that wider subject.

The term typically excludes relief carvings inside caves, whether natural or themselves man-made, which are especially found in Indian rock-cut architecture.

Natural rock formations made into statues or other sculpture in the round, most famously at the Great Sphinx of Giza, are also usually excluded.

An exception was the land of Sumer, where all stone had to be imported over considerable distances, and so the art of Mesopotamia only features rock relief around the edges of the region.

In the many commemorative stelae of Nahr el-Kalb, 12 kilometres north of Beirut, successive imperial rulers have carved memorials and inscriptions.

The reliefs at Nahr el-Kalb commemorate Rameses II,[7] and are at the furthest reach of his empire (indeed beyond the area he reliably controlled) in modern Lebanon.

[10] They are often at sites with a sacred significance both before and after the Hittite period, and apparently places where the divine world was considered as sometimes breaking through to the human one.

[11] At Yazılıkaya, just outside the capital of Hattusa, a series of reliefs of Hittite gods in procession decorate open-air "chambers" made by adding barriers among the natural rock formations.

[12] The Assyrians probably took the form from the Hittites; the sites chosen for their 49 recorded reliefs often also make little sense if "signalling" to the general population was the intent, being high and remote, but often near water.

[15] Probably built by Sennacherib's son Esarhaddon, Shikaft-e Gulgul is a late example in modern Iran, apparently related to a military campaign.

[17] It begins with Lullubi and Elamite rock reliefs, such as those at Kul-e Farah and Eshkaft-e Salman in southwest Iran, and continues under the Assyrians.

The Behistun relief and inscription, made around 500 BC for Darius the Great, is on a far grander scale, reflecting and proclaiming the power of the Achaemenid empire.

[18] Persian rulers commonly boasted of their power and achievements, until the Muslim conquest removed imagery from such monuments; much later there was a small revival under the Qajar dynasty.

[19] Behistun is unusual in having a large and important inscription, which like the Egyptian Rosetta Stone repeats its text in three different languages, here all using cuneiform script: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian (a later form of Akkadian).

[23] Well below the Achaemenid tombs, near ground level, are rock reliefs with large figures of Sassanian kings, some meeting gods, others in combat.

[25] The seven Sassanian reliefs, whose approximate dates range from 225 to 310 AD, show subjects including investiture scenes and battles.

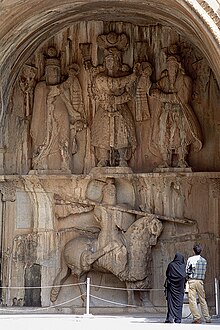

Another important Sassanid site is Taq Bostan with several reliefs including two royal investitures and a famous figure of a cataphract or Persian heavy cavalryman, about twice life size, probably representing the king Khosrow Parviz mounted on his favourite horse Shabdiz; the pair continued to be celebrated in later Persian literature.

[26] Firuzabad, Fars and Bishapur have groups of Sassanian reliefs, the former including the oldest, a large battle scene, now badly worn.

[28] The rock reliefs of the preceding Persian Seleucids and Parthians are generally smaller and more crude, and not all direct royal commissions as the Sassanid ones clearly were.

The standard catalogue of pre-Islamic Persian reliefs lists the known examples (as at 1984) as follows: Lullubi #1–4; Elam #5–19; Assyrian #20–21; Achaemenid #22–30; Late/Post-Achaemenid and Seleucid #31–35; Parthian #36–49; Sasanian #50–84; others #85–88.

[33] Especially at Ajanta, there are many rock reliefs in the open, around the entrances to the caves, either part of the original designs or votive sculptures added later by individual patrons.

Buddhism, originating in India, took the traditions of cave and rock-cut architecture to other parts of Asia, including the creation of rock reliefs.

[39] In these the emphasis shifted to religious subject matter; in earlier reliefs deities had normally appeared only to show their approval of the ruler.

The three famous ancient Buddhist sculptural sites in China are the Mogao Caves,[41] Longmen Grottoes (672–673 for the main group) and Yungang Grottoes (460–535), all of which have colossal Buddha statues in very high relief, cut back into huge niches in the cliff,[42] though the largest figure at Mogao is still enclosed by a wooden image house superstructure in front of it; this is also thought to be a portrait of the reigning empress Wu Zetian.

[47] The Greco-Roman Athena relief of Sömek in modern Turkey, with a warrior nearby, are two of the relatively few examples from the ancient Greek and Roman worlds.

These permanent works formed part of a wider Inca tradition of visualizing and modelling landscapes, often accompanied by rituals.