Buffalo nickel

In 1911, Taft administration officials decided to replace Charles E. Barber's Liberty Head design for the nickel, and commissioned Fraser to do the work.

The designs were approved in 1912, but were delayed several months because of objections from the Hobbs Manufacturing Company, which made mechanisms to detect slugs in nickel-operated machines.

Despite attempts by the Mint to adjust the design, the coins proved to strike indistinctly, and to be subject to wear—the dates were easily worn away in circulation.

[4] In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt expressed his dissatisfaction with the artistic state of American coins,[5] and hoped to hire sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens to redesign all of them.

[6] Andrew was dissatisfied with the Lincoln cent, which was new, and considered seeking congressional authorization to replace it with a design by sculptor James Earle Fraser.

Although the change in the cent did not occur, according to numismatic historian Roger Burdette, "Fraser's enthusiasm eventually led to adoption of the Buffalo nickel in December 1912.

Over the following two weeks, Fraser worked with George Reith, the Hobbs Company's mechanic who had invented the anti-slug device, in an attempt to satisfy the firm's concerns.

On January 20, Fraser wired the Mint from his studio in New York, announcing that he was submitting a modified design, and explained that the delay was "caused by working with inventor until he was satisfied".

[16] The next day, Philadelphia Mint Superintendent John Landis sent Roberts a sample striking of the revised design, stating, "the only change is in the border, which has been made round and true".

[18] Hobbs Company agent C. U. Carpenter suggested that Reith had been intimidated by the preparations that had already gone into the issue of the modified nickel, "and, instead of pointing out clearly just what the situation demanded, agreed to adapt our device to the coin more readily that [sic] he was warranted in doing".

[20] On the fifth, following the conference, which ended with no agreement, Fraser sent MacVeagh a ten-page letter, complaining that his time was being wasted by the Hobbs Company and appealing to the Secretary to bring the situation to a close.

[23] The Secretary noted that no other firm had complained, that the Hobbs mechanism had not been widely sold, and that the changes demanded—a clear space around the rim and the flattening of the Indian's cheekbone—would affect the artistic merit of the piece.

[24] After he issued his decision, MacVeagh learned that the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad Company, which Hobbs claimed had enthusiastically received his device, was actually removing it from service as unsatisfactory.

"[25] Numismatic historian and coin dealer Q. David Bowers describes the Hobbs matter as "much ado about nothing from a company whose devices did not work well even with the Liberty Head nickels".

[26] The first coins to be distributed were given out on February 22, 1913, when Taft presided at groundbreaking ceremonies for the National American Indian Memorial at Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island, New York.

The memorial, a project of department store magnate Rodman Wanamaker, was never built, and today the site is occupied by an abutment for the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.

[29] However, The New York Times stated in an editorial that "The new 'nickel' is a striking example of what a coin intended for wide circulation should not be ...[it] is not pleasing to look at when new and shiny, and will be an abomination when old and dull.

"[30] The Numismatist, in March and May 1913 editorials, gave the new coin a lukewarm review, suggesting that the Indian's head be reduced in size and the bison be eliminated from the reverse.

[35] The new Treasury Secretary, William G. McAdoo, wanted further changes in the coin, but Fraser had moved on to other projects and was uninterested in revisiting the nickel.

[37] The word "LIBERTY" was given more emphasis and moved slightly; however many Denver and San Francisco issues of the 1920s exhibit weak striking of the word, the Denver issue of 1926 especially; Bowers questions whether any change was made to the portrait of the Indian,[38] though Walter Breen in his reference work on United States coins states that Barber made the Indian's nose slightly longer.

According to Breen, however, none of these modifications helped, with the coin rarely found well-struck and with the design subject to considerable wear throughout the remainder of its run.

[39] The bison's horn and tail also posed striking problems, again with the Denver and San Francisco issues of the 1920s in general, and 1926-D in particular, showing the greatest propensity for these deficiencies.

Using materials on hand, including the melting down of worn-out nickels, San Francisco found enough metal to strike 1,000,000 more pieces.

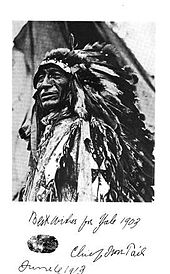

Big Tree was identified as the model for the nickel in wire service reports about his death,[51] and he had appeared in that capacity at the Texas Numismatic Association convention in 1966.

There have been other claimants: in 1964, Montana Senator Mike Mansfield wrote to Mint Director Eva B. Adams, enquiring if Sam Resurrection, a Choctaw, was a model for the nickel.

In an interview published in the New York Herald on January 27, 1913, Fraser was quoted as saying that the animal, which he did not name, was a "typical and shaggy specimen" which he found at the Bronx Zoo.

[53] During an "oral history" interview with the sculptor Beniamino Bufano recorded in 1965, he stated that he "made" and "designed the buffalo" for the coin, when he was Fraser's apprentice.

Colorado Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell[58] in 2001 successfully sponsored a bill for the minting of 500,000 commemorative silver dollars reproducing Fraser's design.

The entire mintage sold out in the span of just weeks and raised 5 million dollars to help in the building of The Smithsonian Museum of The American Indian in Washington, D.C.