Bulgarian Turks

According to the historian Halil Inalcik, the Ottomans ensured significant Turkish presence in forward urban outposts such as Nikopol, Kyustendil, Silistra, Trikala, Skopje and Vidin and their vicinity.

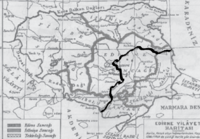

Ottoman Muslims constituted the majority in and around strategic routes primarily in the southern Balkans leading from Thrace towards Macedonia and the Adriatic and again from the Maritsa and Tundzha valleys towards the Danube region.

Most notably, the Christian population in the kazas of Selvi (Sevlievo), Izladi (Zlatitsa), Etripolu (Etropole), Lofça (Lovech), Plevne (Pleven) and Rahova (Oryahovo) is missing as it was written in a different booklet, which was subsequently lost.

After the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) and the establishment of the Principality of Bulgaria and the autonomous province of Eastern Rumelia, the Turkish population in the Bulgarian lands started migrating to the Ottoman Empire and then to modern Turkey.

This was the primary Ottoman destination for Crimean Tatar refugees in the 1850s and 1860s, to the extent they held a plurality in the sanjak's population by 1878 (31.5%), and the region was affectionately nicknamed Küçük Tatarstan (Little Tartary):[60] The data for 1875 is also available as a breakdown by various ethno-confessional groups.

According to estimates reported by the Federal Research Division of the US Library of Congress, 500 to 1,500 people were killed when they resisted assimilation measures, and thousands of others were sent to labor camps or were forcibly resettled.

[114] According to early historical compilations and translations of Ibn Bibi's History of the Seljuq Sultanate of Rum a well founded account is presented of Turkish immigration from Anatolia to Dobruja.

This demographic restructuring was accomplished through colonization of strategic areas of the Balkans with Turks brought or exiled from Anatolia, establishing a firm Turkish Muslim base for further conquests in Europe.

The colonizers that were brought to the Balkans consisted of diverse elements, including groups uneasy for the state, soldiers, nomads, farmers, artisans and merchants, dervishes, preachers and other religious functionaries, and administrative personnel.

[124] After the defeat of Bayezid I at the battle of Ankara by the forces of Tamerlane in 1402, the Ottomans abandoned their Anatolian domains for a while and considered the Balkans their real home, making Adrianople (Edirne) their new capital.

Vakıf deeds and registers of the 15th century show that there was a wide movement of colonization, with western Anatolian peasantry settling in Thrace and the eastern Balkans and founding hundreds of new villages.

[126] Records show that by the end of the 14th century, Muslim Turks formed the absolute majority in large urban towns in Upper Thrace such as Plovdiv (Filibe) and Pazardzhik (Tatar Pazarcik).

Two distinct crafts are evident in Ottoman urban culture that of the architect and that of the master builder (maistores in Macedonia and Epirus, kalfa in Anatolia and sometimes in Bulgaria) who shared the responsibilities and tasks for the design and construction of all sorts of building projects.

The centralized has or hassa (sultan's property and service) system had allowed a small number of architects to control all significant imperial and most vakif building sites over the vast territories of the empire.

[141] The Ottoman army committed numerous atrocities against Christians during its retreat, most notably the complete devastation of Stara Zagora and the surrounding region, which might have provoked some of the attacks against ethnic Turks.

Known contributors in Terbiye Ocağı were Osman Nuri Peremeci, Hafız Abdullah Meçik, Hasip Ahmet Aytuna, Mustafa Şerif Alyanak, Mehmet Mahsum, Osmanpazarli Ibrahim Hakki Oğuz, Ali Avni, Ebuşinasi Hasan Sabri, Hüseyin Edip and Tayyarzade Cemil Bey.

Turkish columnists such as Hasip Saffeti, Ahmet Aytuna, Hafiz Ismail Hakki, Yahya Hayati, Hüsmen Celal, Çetin Ebuşinasi and Hasan Sabri were household names in Deliorman.

In later months the publication of the terms of the Treaty of Berlin naturally intensified the flow of refugees from these areas and according to the prefect of Burgas province as helping themselves to émigré land "in a most arbitrary fashion" [citation needed].

With the mass exodus of Turks after the Treaty of San Stefano the Provisional Administration had little choice but to allow the Bulgarians to work the vacant land with rent, set at half the value of the harvest, to be paid to the legal owner.

In July 1878 the Russian Provisional Administration had come to an agreement with the Porte by which Turkish refugees were allowed to return under military escort, if necessary, and were to have their lands back on condition that they surrendered all their weapons.

[164] After the Communist takeover in 1944, the new regime declared itself in favour of all minorities and inter-ethnic equality and fraternity (in accordance with the classic doctrine of proletarian internationalism) and annulled all the "fascist" anti-Muslim decisions of the previous government.

[180] In March 1973 in the village of Kornitsa situated in the mountainous region of South-West Bulgaria the local Muslim population resisted the forced name changing and attempted to demonstrate against the government's suppressive actions.

[186] On 25 December 1984, close to the town of Benkovski, some 3,000 Turkish protesters from the nearby smaller villages confronted Bulgarian security forces and demanded to have their original identification papers back.

[191][193][194] On 7 July 1987, militants detonates three military fragmentation grenades outside hotel "International" in Golden Sands resort at the time occupied with East German holiday-makers, trying to get attention and publicity for the renaming process.

[195] On 6 May, members of the Turkish community initiated mass hunger strikes and demanded the restitution of their Muslim names and civil liberties in accordance with the country's constitution and international treaties signed by Bulgaria.

The Bulgarian Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights and Religious Freedom approved in February 2010 a declaration, condemning the Communist regime's attempt to forcefully assimilate the country's ethnic Turkish population.

In January 1990, the Social Council of Citizens, a national body representing all political and ethnic groups, reached a compromise that guaranteed the Turks freedom of religion, choice of names, and unimpeded practice of cultural traditions and use of Turkish within the community.

[211] These conditions forced the government to find a balance between Turkish demands and demonstrations for full recognition of their culture and language, and some Bulgarians' concerns about preferential treatment for the ethnic minority.

Frustration with unmet promises encouraged Turkish separatists in both Bulgaria and Turkey, which in turn fueled the ethnocentric fears of the Bulgarian majority[citation needed] —and the entire issue diverted valuable energy from the national reform effort.

The group's specific goals were ensuring that the new constitution protect ethnic minorities adequately; introducing Turkish as an optional school subject; and bringing to trial the leaders of the assimilation campaign in the 1980s.