Buruli ulcer

The mechanism by which M. ulcerans is transmitted from the environment to humans is not known but may involve the bite of an aquatic insect or the infection of open wounds.

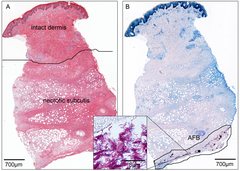

Once in the skin, M. ulcerans grows and releases the toxin mycolactone, which blocks the normal function of cells, resulting in tissue death and immune suppression at the site of the ulcer.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends treating Buruli ulcers with a combination of the antibiotics rifampicin and clarithromycin.

Deep ulcers and those on sensitive body sites may require surgery to remove dead tissue or repair scarred muscles or joints.

The first sign of Buruli ulcer is a painless swollen bump on the arm or leg, often similar in appearance to an insect bite.

Mycolactone diffuses into host cells and blocks the action of Sec61, the molecular channel that serves as a gateway to the endoplasmic reticulum.

[13] When Sec61 is blocked, proteins that would normally enter the endoplasmic reticulum are mistargeted to the cytosol, causing a pathological stress response that leads to cell death by apoptosis.

[11] In areas endemic for Buruli ulcer, disease occurs near stagnant bodies of water, leading to the long-standing hypothesis that M. ulcerans is somehow transmitted to humans from aquatic environments.

[17] Wearing pants and long-sleeved shirts is associated with a lower risk of Buruli ulcer, possibly by preventing insect bites or protecting wounds.

[11][17] While Buruli ulcer is not contagious, susceptibility sometimes runs in families, suggesting genetics could play a role in who develops the disease.

Severe Buruli ulcer in a Beninese family was attributed to a loss of 37 kilobases of chromosome 8 in a region that included a long non-coding RNA and was near the genes for beta-defensins, which are antimicrobial peptides involved in immunity and wound healing.

[18] As Buruli ulcer most commonly occurs in low-resource settings, treatment is often initiated by a clinician based on signs and symptoms alone.

The nodule that appears early in the disease can resemble a bug bite, sebaceous cyst, lipoma, onchocerciasis, other mycobacterial skin infections, or an enlarged lymph node.

[4] Skin ulcers can resemble those caused by leishmaniasis, yaws, squamous cell carcinoma, Haemophilus ducreyi infection, and tissue death due to poor circulation.

[27] Approximately 1 in 5 people with Buruli ulcer experience a temporary worsening of symptoms 3 to 12 weeks after they begin taking antibiotics.

[28] The paradoxical reaction in Buruli ulcer is thought to be due to the immune system responding to the wound as bacteria die and the immune-suppressing mycolactone dissipates.

[26] The risk of acquiring it can be reduced by wearing long sleeves and pants, using insect repellent, and cleaning and covering any wounds as soon as they are noticed.

[1] Most countries do not report data on Buruli ulcer to the World Health Organization, and the extent of its spread is unknown.

[32][33] In many endemic countries, health systems likely do not record each case due to insufficient reach and resources, and so the reported numbers probably underestimate the true prevalence of the disease.

[34] Buruli ulcer is concentrated in West Africa and coastal Australia, with occasional cases in Japan, Papua New Guinea, and the Americas.

In West Africa, the disease is predominantly reported from remote, rural communities in Benin, Côte d'Ivoire, Cameroon, and Ghana.

[33] Buruli ulcer is regularly reported from Australia, where it occurs in coastal clusters—two in Queensland (near Rockhampton and north of Cairns) and two in Victoria (near Bairnsdale and Melbourne).

[11] In particular, the disease tends to appear near water that has experienced human intervention, such as the building of dams or irrigation systems, flooding, or deforestation.

[11] Ulcers can appear in people of all ages, although infections are most common among children between 5 and 15 years in West Africa, and adults over 40 in Australia and Japan.

Injection of M. ulcerans can cause ulcers in several rodents (mice, guinea pigs, greater cane rats and common African rats), larger mammals (nine-banded armadillos, common brushtail possums, pigs, and Cynomolgus monkeys), and anole lizards.

[44] Those with Buruli ulcer report feeling shame and experiencing social stigma that could affect their relationships, school attendance, and marriage prospects.

[47][53] The cause of these slow-healing ulcers was identified 50 years later in 1948, when Peter MacCallum, Jean Tolhurst, Glen Buckle, and H. A. Sissons at The Alfred Hospital's Baker Institute described a series of cases from Bairnsdale, Victoria, isolated the causative mycobacterium, and showed it could cause ulcers in laboratory rats.

[57] From the time the disease was described, Buruli ulcer was treated with surgery to remove all affected tissue, followed by prolonged wound care.

[58] Treatment dramatically improved in 2004, when the World Health Organization recommended an eight-week course of daily oral rifampicin and injected streptomycin.

[60] Since M. ulcerans can only grow in relatively cool temperatures, mice are typically infected in furless parts of the body: the ear, tail, or footpad.