Bus deregulation in Great Britain

[1] The postwar Labour government had a policy of nationalising public transport and was in compulsory purchase negotiations with bus companies during the post-war period.

Ken Livingstone, leader of the Greater London Council in the early 1980s, adopted a policy of open hostility to the Westminster government.

Most large private bus companies in England included a core industrialised urban area which was profitable, and a rural expanse which either barely covered costs or lost money.

Fares had largely remained unchanged since 1930 partially due to companies growing by acquisition – safe from the threat of new market entrants – but opportunities to improve profitability through consolidation were eventually exhausted.

This made full staffing of bus services easier at a time of labour shortage, and lowered costs significantly in a labour-intensive industry.

Prior to this, bus companies negotiated with traffic commissioners on these issues as part of meeting their Road Service Licence obligations.

Conservative governments at that time favoured redistributing bus resources to their often more rural constituencies, whereas Labour's electoral base was more urban and sought to lower fares and introduce additional services in cities.

Competition cases meant that privately owned bus stations had to be open and available on a non-discriminatory basis to all operators.

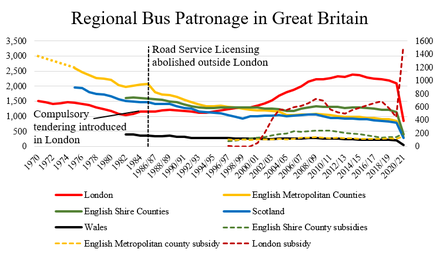

The Conservative government at the time argued that the abolition of restrictive licensing would increase patronage by allowing bus operators to respond more quickly to passengers' needs.

While bus networks did change radically, maintenance of market position, or fighting existential threat, was the dominant driver of operators' behaviour immediately after deregulation.

Patronage continued to decline across Great Britain, but its impact was uneven; the English "shire counties" saw a continued decline in line with previous trends, as local governments' resources were diverted towards their relatively larger settlements and away from smaller villages as resources were prioritised to serve as many people as possible.

[5] Deregulation and privatisation failed to address the primary cause of decline in patronage, which was surrounded by rising car ownership, such as the abundance of cheap or free parking, car-oriented housing development, and the growth of out-of-town retail centres, which all drove forward the decline in bus patronage.

Intense competition sometimes resulted in a bus war, requiring the intervention of the authorities to stamp out unscrupulous or unsafe practices.

[11] Between March 2000 and July 2002, First Scotland East sought to increase its market share of local bus services in and around Edinburgh.

As a result, a bus war sparked between FirstGroup and Lothian Buses, with fares cut, additional vehicles drafted in, routes diverted, and timetables altered.

Lothian Buses complained to the Office of Fair Trading, claiming that FirstGroup was engaging in anti-competitive behaviour in an effort to become the dominant operator in Edinburgh.

Many inflexible practices which had accumulated and were standard across the bus sector prior to deregulation were removed; differing wage rates for driving different vehicles, which were in some cases allocated on seniority as part of collective bargaining agreements or as part of a side agreement (minibuses were largely introduced as a workaround), demarcation disputes, maintenance of pay differentials, inflexible rostering were phased out as incumbent operators struggled to survive the threat from new market entrants who had no such restrictions.

[23] When deregulation started, there was an explosion of new entrants to the local bus market – the most notable being Stagecoach, which began as a long-distance coach operator.

Many district councils' bus departments were sold or went bust due to the difficulty abandoning old practices such as route cross-subsidy, transporting school pupils without financial compensation from the local authority, and inflexible collective bargaining agreements agreed long before deregulation.

[citation needed] As of 2010, the big five operators – Arriva, First, Go-Ahead, National Express, and Stagecoach – controlled 70% of the market.

[27] Opposers have claimed that since deregulation and privatisation, passenger numbers of UK buses have declined, fare costs have "skyrocketed", and services have become unreliable.

[36] In October 2023, the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority announced that it would use the Act's powers to bring buses under public control.

[37] The West Yorkshire Combined Authority has also expressed support for the franchising of bus services,[38] but with an expectation that it may not be completed until 2027.