Business Plot

[2][3] Butler, a retired Marine Corps major general, testified under oath that wealthy businessmen were plotting to create a fascist veterans' organization with him as its leader and use it in a coup d'état to overthrow Roosevelt.

[4] Although no one was prosecuted, the congressional committee final report said, "there is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient."

Early in the committee's gathering of testimony most major news media dismissed the plot, with a New York Times editorial characterizing it as a "gigantic hoax".

[5] When the committee's final report was released, the Times said the committee "purported to report that a two-month investigation had convinced it that General Butler's story of a Fascist march on Washington was alarmingly true" and "... also alleged that definite proof had been found that the much publicized Fascist march on Washington, which was to have been led by Major Gen. Smedley D. Butler, retired, according to testimony at a hearing, was actually contemplated".

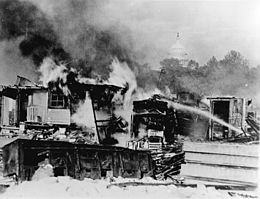

[11] A few days after Butler's arrival, President Herbert Hoover ordered the marchers removed and U.S. Army cavalry troops under the command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur destroyed their camps.

They viewed a currency not solidly backed by gold as inflationary, undermining both private and business fortunes and leading to national bankruptcy.

Roosevelt was damned as a socialist or Communist out to destroy private enterprise by sapping the gold backing of wealth in order to subsidize the poor.

[16] During the committee hearings, Butler testified that Gerald C. MacGuire attempted to recruit him to lead a coup, promising him an army of 500,000 men for a march on Washington, D.C., and financial backing.

Given a successful coup, Butler said that the plan was for him to have held near-absolute power in the newly created position of "Secretary of General Affairs", while Roosevelt would have assumed a figurehead role.

MacGuire was a $100-a-week bond salesman for Wall Street banking firm Grayson Murphy & Company[25][26] and a member of the Connecticut American Legion.

"It urged the American Legion convention to adopt a resolution calling for the United States to return to the gold standard, so that when veterans were paid the bonus promised to them, the money they received would not be worthless paper.

[46]On November 21, 1934, one day into the committee gathering testimony, The New York Times ran an article with the headline, "Gen. Butler Bares 'Fascist Plot' To Seize Government by Force; Says Bond Salesman, as Representative of Wall St. Group, Asked Him to Lead Army of 500,000 in March on Capital – Those Named Make Angry Denials – Dickstein Gets Charge".

[citation needed] A November 22, 1934, New York Times editorial published just two days into committee testimony dismissed Butler's story as "a gigantic hoax" and a "bald and unconvincing narrative.

"[5][45] Time magazine reported on December 3, 1934, that the committee "alleged that definite proof had been found that the much publicized Fascist march on Washington, which was to have been led by Maj. Gen. Smedley D. Butler, retired, according to testimony at a hearing, was actually contemplated".

"[49] Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. said in 1958, "Most people agreed with Mayor La Guardia of New York in dismissing it as a 'cocktail putsch'".

[50] In Schlesinger's summation of the affair in 1958, "No doubt, MacGuire did have some wild scheme in mind, though the gap between contemplation and execution was considerable, and it can hardly be supposed that the Republic was in much danger.

"[7] Historian Hans Schmidt wrote, "Even if Butler was telling the truth, as there seems little reason to doubt, there remains the unfathomable problem of MacGuire's motives and veracity.

If he was acting as an intermediary in a genuine probe, or as agent provocateur sent to fool Butler, his employers were at least clever enough to keep their distance and see to it that he self-destructed on the witness stand.

During the end of the film, a clip of Dillenbeck speaking before the congressional committee is played alongside footage of Butler's actual testimony, revealing it to be the same speech.