Butterfly effect

[1][2] He discovered the effect when he observed runs of his weather model with initial condition data that were rounded in a seemingly inconsequential manner.

[3] The idea that small causes may have large effects in weather was earlier acknowledged by the French mathematician and physicist Henri Poincaré.

[4] The concept of the butterfly effect has since been used outside the context of weather science as a broad term for any situation where a small change is supposed to be the cause of larger consequences.

In The Vocation of Man (1800), Johann Gottlieb Fichte says "you could not remove a single grain of sand from its place without thereby ... changing something throughout all parts of the immeasurable whole".

[5] In 1950, Alan Turing noted: "The displacement of a single electron by a billionth of a centimetre at one moment might make the difference between a man being killed by an avalanche a year later, or escaping.

"[7] The idea that the death of one butterfly could eventually have a far-reaching ripple effect on subsequent historical events made its earliest known appearance in "A Sound of Thunder", a 1952 short story by Ray Bradbury.

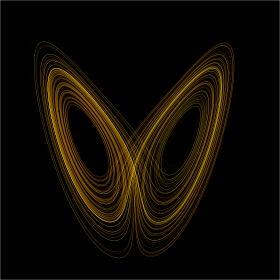

In 1963, Lorenz published a theoretical study of this effect in a highly cited, seminal paper called Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow[3][11] (the calculations were performed on a Royal McBee LGP-30 computer).

[12][13] Elsewhere he stated: One meteorologist remarked that if the theory were correct, one flap of a sea gull's wings would be enough to alter the course of the weather forever.

According to Lorenz, when he failed to provide a title for a talk he was to present at the 139th meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1972, Philip Merilees concocted Does the flap of a butterfly's wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?

The flapping wing creates a small change in the initial condition of the system, which cascades to large-scale alterations of events (compare: domino effect).

The butterfly effect presents an obvious challenge to prediction, since initial conditions for a system such as the weather can never be known to complete accuracy.

[19] Recent studies using generalized Lorenz models that included additional dissipative terms and nonlinearity suggested that a larger heating parameter is required for the onset of chaos.

A dynamical system displays sensitive dependence on initial conditions if points arbitrarily close together separate over time at an exponential rate.

The climate scientists James Annan and William Connolley explain that chaos is important in the development of weather prediction methods; models are sensitive to initial conditions.

They add the caveat: "Of course the existence of an unknown butterfly flapping its wings has no direct bearing on weather forecasts, since it will take far too long for such a small perturbation to grow to a significant size, and we have many more immediate uncertainties to worry about.

The two kinds of butterfly effects, including the sensitive dependence on initial conditions,[3] and the ability of a tiny perturbation to create an organized circulation at large distances,[1] are not exactly the same.

[28] In Palmer et al.,[22] a new type of butterfly effect is introduced, highlighting the potential impact of small-scale processes on finite predictability within the Lorenz 1969 model.

[25] These two distinct mechanisms suggesting finite predictability in the Lorenz 1969 model are collectively referred to as the third kind of butterfly effect.

The third kind of butterfly effect with finite predictability, as discussed in,[22] was primarily proposed based on a convergent geometric series, known as Lorenz's and Lilly's formulas.

[29] In recent studies,[25][31] it was reported that both meteorological and non-meteorological linear models have shown that instability plays a role in producing a butterfly effect, which is characterized by brief but significant exponential growth resulting from a small disturbance.

The first kind of butterfly effect (BE1), known as SDIC (Sensitive Dependence on Initial Conditions), is widely recognized and demonstrated through idealized chaotic models.

[32][33] In more recent discussions published by Physics Today,[34][35] it is acknowledged that the second kind of butterfly effect (BE2) has never been rigorously verified using a realistic weather model.

While the studies suggest that BE2 is unlikely in the real atmosphere,[32][34] its invalidity in this context does not negate the applicability of BE1 in other areas, such as pandemics or historical events.

[36] For the third kind of butterfly effect, the limited predictability within the Lorenz 1969 model is explained by scale interactions in one article[22] and by system ill-conditioning in another more recent study.

[25] According to Lighthill (1986),[37] the presence of SDIC (commonly known as the butterfly effect) implies that chaotic systems have a finite predictability limit.

The hypothesis supports the investigation into extended-range predictions using both partial differential equation (PDE)-based physics methods and Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques.

On the other hand, when two kayaks move into a stagnant area, they become trapped, showing no typical SDIC (although a chaotic transient may occur).

By taking into consideration time-varying multistability that is associated with the modulation of large-scale processes (e.g., seasonal forcing) and aggregated feedback of small-scale processes (e.g., convection), the above revised view is refined as follows: "The atmosphere possesses chaos and order; it includes, as examples, emerging organized systems (such as tornadoes) and time varying forcing from recurrent seasons.

"[48][49] The potential for sensitive dependence on initial conditions (the butterfly effect) has been studied in a number of cases in semiclassical and quantum physics, including atoms in strong fields and the anisotropic Kepler problem.

[52][59] The butterfly effect has appeared across mediums such as literature (for instance, A Sound of Thunder), films and television (such as The Simpsons), video games (such as Life Is Strange), webcomics (such as Homestuck), AI-driven expansive language models, and more.