Buzz Aldrin

Born in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, Aldrin graduated third in the class of 1951 from the United States Military Academy at West Point with a degree in mechanical engineering.

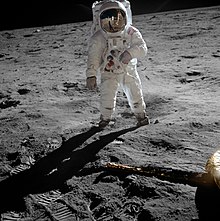

Three years later, Aldrin set foot on the Moon at 03:15:16 on July 21, 1969 (UTC), nineteen minutes after Armstrong first touched the surface, while command module pilot Michael Collins remained in lunar orbit.

[18] In December 1954 he became an aide-de-camp to Brigadier General Don Z. Zimmerman, the Dean of Faculty at the nascent United States Air Force Academy, which opened in 1955.

After White left West Germany to study for a master's degree at the University of Michigan in aeronautical engineering, he wrote to Aldrin encouraging him to do the same.

"[33] Aldrin chose his doctoral thesis in the hope that it would help him be selected as an astronaut, although it meant foregoing test pilot training, which was a prerequisite at the time.

He was then posted to the Space Systems Division's field office at NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, where he was involved in integrating Department of Defense experiments into Project Gemini flights.

It dropped the test of the Air Force's astronaut maneuvering unit (AMU) that had given Gordon trouble on Gemini 11 so Aldrin could focus on EVA.

Aldrin used a sextant and rendezvous charts he helped create to give Lovell the right information to put the spacecraft in position to dock with the target vehicle.

[50][53] On November 15, the crew initiated the automatic reentry system and splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean, where they were picked up by a helicopter, which took them to the awaiting aircraft carrier USS Wasp.

Multiple factors contributed to the final decision, including the physical positioning of the astronauts within the compact lunar lander, which made it easier for Armstrong to be the first to exit the spacecraft.

[66][67] Propelled by a Saturn V rocket, Apollo 11 lifted off from Launch Complex 39 at the Kennedy Space Center on July 16, 1969, at 13:32:00 UTC (9:32:00 EDT),[68] and entered Earth orbit twelve minutes later.

[69] In the thirty orbits that followed,[70] the crew saw passing views of their landing site in the southern Sea of Tranquillity about 12 miles (19 km) southwest of the crater Sabine D.[71] At 12:52:00 UTC on July 20, Aldrin and Armstrong entered Eagle, and began the final preparations for lunar descent.

[74] Five minutes into the descent burn, and 6,000 feet (1,800 m) above the surface of the Moon, the LM guidance computer (LGC) distracted the crew with the first of several unexpected alarms that indicated that it could not complete all its tasks in real time and had to postpone some of them.

[75] Due to the 1202/1201 program alarms caused by spurious rendezvous radar inputs to the LGC,[76] Armstrong manually landed the Eagle instead of using the computer's autopilot.

He radioed Earth: "I'd like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever and wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours, and to give thanks in his or her own way.

Aldrin positioned himself in front of the video camera and began experimenting with different locomotion methods to move about the lunar surface to aid future moonwalkers.

While Armstrong inspected a crater, Aldrin began the difficult task of hammering a metal tube into the surface to obtain a core sample.

[93] With some difficulty they lifted film and two sample boxes containing 21.55 kilograms (47.5 lb) of lunar surface material to the hatch using a flat cable pulley device.

[99] Bringing back pathogens from the lunar surface was considered a possibility, albeit remote, so divers passed biological isolation garments (BIGs) to the astronauts, and assisted them into the life raft.

The astronauts were winched on board the recovery helicopter, and flown to the aircraft carrier USS Hornet,[100] where they spent the first part of the Earth-based portion of 21 days of quarantine.

[103][104] On September 16, 1969, the astronauts addressed a joint session of Congress where they thanked the representatives for their past support and implored them to continue funding the space effort.

[118] Aldrin's autobiographies, Return to Earth (1973) and Magnificent Desolation (2009), recounted his struggles with clinical depression and alcoholism in the years after leaving NASA.

Aldrin helped to develop UND's Space Studies program and brought David Webb from NASA to serve as the department's first chair.

[144] During a 1966 ceremony marking the end of the Gemini program, Aldrin was awarded the NASA Exceptional Service Medal by President Johnson at LBJ Ranch.

[160] The National Space Club named the crew the winners of the 1970 Dr. Robert H. Goddard Memorial Trophy, awarded annually for the greatest achievement in spaceflight.

[165] In 1970, the Apollo 11 team were co-winners of the Iven C. Kincheloe award from the Society of Experimental Test Pilots along with Darryl Greenamyer who broke the world speed record for piston engine airplanes.

[168] Aldrin received the 2003 Humanitarian Award from Variety, the Children's Charity, which, according to the organization, "is given to an individual who has shown unusual understanding, empathy, and devotion to mankind.

[185][186] In 2018, Aldrin was involved in a legal dispute with his children Andrew and Janice and former business manager Christina Korp over their claims that he was mentally impaired through dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

[195] Aldrin cited Trump's promotion of space exploration policy as a reason for his endorsement, claiming that interest in it has waned in previous years.

[200] In 2007, Aldrin confirmed to Time magazine that he had recently had a face-lift, joking that the g-forces he was exposed to in space "caused a sagging jowl that needed some attention".