Byzantine music

[2] The Byzantine system of octoechos, in which melodies were classified into eight modes, is specifically thought to have been exported from Syria, where it was known in the 6th century, before its legendary creation by Arab monk John of Damascus of the Umayyad Caliphate.

[9] The Pythagorean sect and music as part of the four "cyclical exercises" (ἐγκύκλια μαθήματα) that preceded the Latin quadrivium and science today based on mathematics, established mainly among Greeks in southern Italy (at Taranto and Crotone).

But they made no use of earlier Pythagorean concepts that had been fundamental for Byzantine music, including: It is not evident by the sources, when exactly the position of the minor or half tone moved between the devteros and tritos.

Dio Chrysostom wrote in the 1st century of a contemporary sovereign (possibly Nero) who could play a pipe (tibia, Roman reedpipes similar to Greek aulos) with his mouth as well as by tucking a bladder beneath his armpit.

[22] Secular music existed and accompanied every aspect of life in the empire, including dramatic productions, pantomime, ballets, banquets, political and pagan festivals, Olympic games, and all ceremonies of the imperial court.

[25] The documented polychronia in books of the cathedral rite allow a geographical and a chronological classification of the manuscript and they are still used during ektenies of the divine liturgies of national Orthodox ceremonies today.

The allusion is perpetuated in the writings of the early Fathers, such as Clement of Rome, Justin Martyr, Ignatius of Antioch, Athenagoras of Athens, John Chrysostom and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite.

This dramatic homily which could treat various subjects, theological and hagiographical ones as well as imperial propaganda, comprises some 20 to 30 stanzas (oikoi "houses") and was sung in a rather simple style with emphasise on the understanding of the recent texts.

The troparion "Οἱ τὰ χερουβεὶμ", which was sung during the procession, was often ascribed to Emperor Justin II, but the changes in sacred architecture were definitely traced back to his time by archaeologists.

[43]By the end of the seventh century with the reform of 692, the kontakion, Romanos' genre was overshadowed by a certain monastic type of homiletic hymn, the canon and its prominent role it played within the cathedral rite of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem.

Out of the custom of canticle recitation, monastic reformers at Constantinople, Jerusalem and Mount Sinai developed a new homiletic genre whose verses in the complex ode meter were composed over a melodic model: the heirmos.

After the octoechos reform of the Quinisext Council in 692, monks at Mar Saba continued the hymn project under Andrew's instruction, especially by his most gifted followers John of Damascus and Cosmas of Jerusalem.

[51] Nevertheless, the form tropologion was used until the 12th century, and many later books which combined octoechos, sticherarion and heirmologion, rather derive from it (especially the usually unnotated Slavonic osmoglasnik which was often divided in two parts called "pettoglasnik", one for the kyrioi, another for the plagioi echoi).

On the other hand, Constantinople as well as other parts of the Empire like Italy encouraged also privileged women to found female monastic communities and certain hegumeniai also contributed to the hymnographic reform.

Another project of the Studites' reform was the organisation of the New Testament (Epistle, Gospel) reading cycles, especially its hymns during the period of the triodion (between the pre-Lenten Meatfare Sunday called "Apokreo" and the Holy Week).

It seems that until the time, when the Hagiopolites was written, the octoechos reform did not work out for the cathedral rite, because singers at the court and at the Patriarchate still used a tonal system of 16 echoi, which was obviously part of the particular notation of their books: the asmatikon and the kontakarion or psaltikon.

The former genre and glory of Romanos' kontakion was not abandoned by the reformers, even contemporary poets in a monastic context continued to compose new liturgical kontakia (mainly for the menaion), it likely preserved a modality different from Hagiopolitan oktoechos hymnography of the sticherarion and the heirmologion.

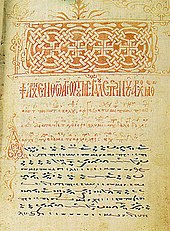

The manuscript was rubrified Κονδακάριον σῦν Θεῷ by the scribe, the rest is not easy to decipher since the first page was exposed to all kinds of abrasion, but it is obvious that this book is a collection of short kontakia organised according to the new menaion cycle like a sticherarion, beginning with 1 September and the feast of Symeon the Stylite.

The adaption to the menaion of the Rus rather proves that notation was only used in a few parts, where a new translation of a certain text required a new melodic composition which was no longer included within the existing system of melodies established by the Stoudites and their followers.

[68] The reason is that their translation of Greek hymnography were not very literal, but often quite far from the content of the original texts, the main concern of this school was the recomposition or troping of the given system of melodies (with their models known as avtomela and heirmoi) which was left intact.

In the Primary Chronicle it is reported, how a legacy of the Rus' was received in Constantinople and how they did talk about their experience in presence of Vladimir the Great in 987, before the Grand Prince Vladimir decided about the Christianization of the Kievan Rus' (Laurentian Codex written at Nizhny Novgorod in 1377): On the morrow, the Byzantine emperor sent a message to the patriarch to inform him that a Russian delegation had arrived to examine the Greek faith, and directed him to prepare the church Hagia Sophia and the clergy, and to array himself in his sacerdotal robes, so that the Russians might behold the glory of the God of the Greeks.

The emperor accompanied the Russians to the church, and placed them in a wide space, calling their attention to the beauty of the edifice, the chanting, and the offices of the archpriest and the ministry of the deacons, while he explained to them the worship of his God.

[78] A comparison with Easter koinonikon proves two things: the Slavic kondakar' did not correspond to the "pure" form of the Greek kontakarion which was the book of the soloist who had also to recite the larger parts of the kontakia or kondaks.

It contained the refrains (dochai) of the prokeimena, troparia, sometimes the ephymnia of the kontakia and the hypakoai, but also ordinary chant of the divine liturgy like the eisodikon, the trisagion, the choir sections of the cherubikon asmatikon, the weekly and annual cycle of koinonika.

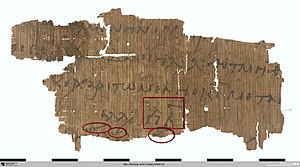

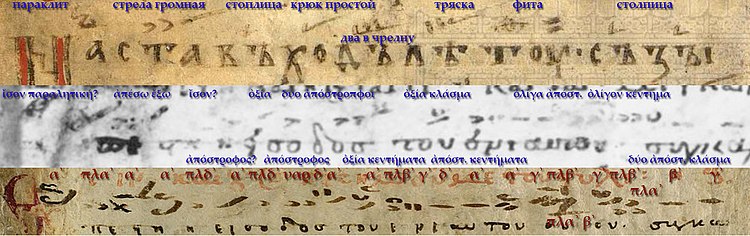

Nothing is known about the exact division of the tetrachord, because no treatise concerned with the tradition the cathedral rite of Constantinople has survived, but the Coislin sign of xeron klasma (ξηρὸν κλάσμα) appeared on different pitch classes (phthongoi) than within the stichera idiomela of the sticherarion.

Both Slavonic kondaks follow strictly the melismatic structure in the music and the frequent segmentation by kola (which does not exist in the Middle Byzantine version), interrupting the conclusion of the first text unit by an own kolon using with the asmatic syllable "ɤ".

Even among the notated sources there was a distinction between the short and the long psaltikon style which was based on the musical setting of the kontakia, established by Christian Thodberg and by Jørgen Raasted.

One part of this process was the redaction and limitation of the present repertoire given by the notated chant books of the sticherarion (menaion, triodion, pentekostarion, and oktoechos) and the heirmologion during the 14th century.

It emerged as the result of a sharing process between the many civilizations that met together in the Orient, considering the breadth and length of duration of these empires and the great number of ethnicities and major or minor cultures that they encompassed or came in touch with at each stage of their development.

Токмо то вемы, яко онъде Богъ с человеки пребываеть, и есть служба их паче всехъ [verso] странах.