Charles Stewart Parnell

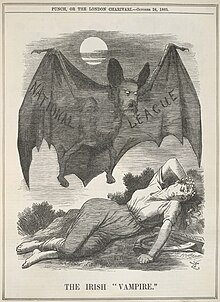

He became leader of the Home Rule League, operating independently of the Liberal Party, winning great influence by his balancing of constitutional, radical, and economic issues, and by his skilful use of parliamentary procedure.

The Irish Parliamentary Party split in 1890, following the revelation of Parnell's long adulterous love affair, which led to many British Liberals, many of whom were Nonconformists, refusing to work with him, and engendered strong opposition from Catholic bishops.

The young Parnell studied at Magdalene College, Cambridge (1865–1869) but, due to the troubled financial circumstances of the estate he inherited, he was absent a great deal and never completed his degree.

In 1871, he joined his elder brother John Howard Parnell (1843–1923), who farmed in Alabama (later an Irish Parnellite MP and heir to the Avondale estate), on an extended tour of the United States.

[1] His attention was drawn to the theme dominating the Irish political scene of the mid-1870s, Isaac Butt's Home Rule League formed in 1873 to campaign for a moderate degree of self-government.

[1][4] In December 1877, at a reception for Michael Davitt on his release from prison, he met William Carrol who assured him of Clan na Gael's support in the struggle for Irish self-government.

This was followed by a telegram from John Devoy in October 1878 which offered Parnell a "New Departure" deal of separating militancy from the constitutional movement as a path to all-Ireland self-government, under certain conditions: abandonment of a federal solution in favour of separatist self-government, vigorous agitation in the land question on the basis of peasant proprietorship, exclusion of all sectarian issues, collective voting by party members and energetic resistance to coercive legislation.

At a national level, several approaches were made which eventually produced the "New Departure" of June 1879, endorsing the foregone informal agreement which asserted an understanding binding them to mutual support and a shared political agenda.

Historian R. F. Foster argues that in the countryside the Land League "reinforced the politicization of rural Catholic nationalist Ireland, partly by defining that identity against urbanization, landlordism, Englishness and—implicitly—Protestantism.

"[10] Parnell's own newspaper, the United Ireland, attacked the Land Act[4] and he was arrested on 13 October 1881, together with his party lieutenants, William O'Brien, John Dillon, Michael Davitt and Willie Redmond, who had also conducted a bitter verbal offensive.

[11] His release on 2 May, following the so-called Kilmainham Treaty, marked a critical turning point in the development of Parnell's leadership when he returned to the parameters of parliamentary and constitutional politics,[12] and resulted in the loss of support of Devoy's American-Irish.

His political diplomacy preserved the national Home Rule movement after the Phoenix Park killings of the Chief Secretary Lord Frederick Cavendish, and his Under-Secretary, T. H. Burke on 6 May.

It combined moderate agrarianism, a Home Rule programme with electoral functions, was hierarchical and autocratic in structure with Parnell wielding immense authority and direct parliamentary control.

Parnell saw that the explicit endorsement of Catholicism was of vital importance to the success of this venture and worked in close cooperation with the Catholic hierarchy in consolidating its hold over the Irish electorate.

[17] Parnell left the day-to-day running of the INL in the hands of his lieutenants Timothy Harrington as Secretary, William O'Brien, editor of its newspaper United Ireland, and Tim Healy.

Parnell next turned to the Home Rule League Party, of which he was to remain the re-elected leader for over a decade, spending most of his time at Westminster, with Henry Campbell as his personal secretary.

In March 1885, the British cabinet rejected the proposal of radical minister Joseph Chamberlain of democratic county councils which in turn would elect a Central Board for Ireland.

The November general elections (delayed because boundaries were being redrawn and new registers prepared after the Third Reform Act) brought about a hung Parliament in which the Liberals with 335 seats won 86 more than the Conservatives, with a Parnellite bloc of 86 Irish Home Rule MPs holding the balance of power in the Commons.

The third Gladstone administration paved the way towards the generous response to Irish demands that the new Prime Minister had promised,[20] but was unable to obtain the support of several key players in his own party.

The Liberal split made the Unionists (the Liberal Unionists sat in coalition with the Conservatives after 1895 and would eventually merge with them) the dominant force in British politics until 1906, with strong support in Lancashire, Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham (the fiefdom of its former mayor Joseph Chamberlain who as recently as 1885 had been a furious enemy of the Conservatives) and the House of Lords where many Whigs sat (a second Home Rule Bill would pass the Commons in 1893 only to be overwhelmingly defeated in the Lords).

Parnell next became the centre of public attention when in March and April 1887 he found himself accused by the British newspaper The Times of supporting the brutal murders in May 1882 of the newly appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish, and the Permanent Under-Secretary, Thomas Henry Burke, in Dublin's Phoenix Park, and of the general involvement of his movement with crime (i.e., with illegal organisations such as the IRB).

Chas S. Parnell.A Commission of Enquiry, which Parnell had requested, revealed in February 1889, after 128 sessions that the letters were a fabrication created by Richard Pigott, a disreputable anti-Parnellite rogue journalist.

On each occasion, Parnell's demands were entirely within the accepted parameters of Liberal thinking, Gladstone noting that he was one of the best people he had known to deal with,[1] a remarkable transition from an inmate at Kilmainham to an intimate at Hawarden in just over seven years.

On 6 December, after five days of vehement debate, a majority of 44 present led by Justin McCarthy walked out to found a new organisation, thus creating rival Parnellite and anti-Parnellite parties.

On the same day, the Irish Catholic hierarchy, worried by the number of priests who had supported him in North Sligo, signed and published a near-unanimous condemnation: "by his public misconduct, has utterly disqualified himself to be ...

An effective communicator, he was skilfully ambivalent and matched his words depending on circumstances and audience, but he would always first defend constitutionalism on which basis he sought to bring about change, but he was hampered by the crimes that hung around the Land League and by the opposition of landlords against the attacks on their property.

[1] Parnell's personal complexities or his perception of a need for political expediency to his goal permitted him to condone the radical republican and atheist Charles Bradlaugh, while he associated himself with the hierarchy of the Catholic Church.

Andrew Kettle, Parnell's right-hand man, who shared many of his opinions, wrote of his own views, "I confess that I felt [in 1885], and still feel, a greater leaning towards the British Tory party than I ever could have towards the so-called Liberals".

His leading biographer, F. S. L. Lyons, says historians emphasise numerous major achievements: Above all there is the emphasis on constitutional action, as historians point to the Land Act 1881; the creation of the powerful third force in Parliament using a highly disciplined party that he controlled; the inclusion of Ireland in the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881, while preventing any reduction in the number of Irish seats; the powerful role of the Irish National League and organising locally, especially County conventions that taught peasants about democratic self-government; forcing Home Rule to be a central issue in British politics; and persuading the great majority of the Liberal party to adopt his cause.

"[55] Parnell is the subject of a discussion in Irish author James Joyce's first chapter of the semi-autobiographical novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, first serialised in The Egoist magazine in 1914–15.