Ca' Morta tomb

Thanks to the exceptional quality of the objects unearthed, this tomb is a precious testimony to Celtic culture at the time, particularly in terms of craft techniques, intra-European trade and the role of women in society.

Numerous items of Etruscan laminated bronze crockery and Attic black-figure and red-figure ceramics evoke trade relations with Padanian Etruria on the one hand, and Magna Graecia and the Italic territories on the other.

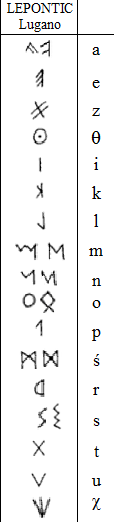

Finally, numerous elements - ancient, epigraphic, and archaeological sources - indicate that the woman, whose cremated remains lie in the urn of "tomb III/1928", was probably of Orobian stock, and that her mother tongue was Lepontic.

[1][2] Antonio Giussani of the Società Archeologica Comense (Comascan Archaeological Society[notes 7])[1][3] carried out the extraction, identification and inventory of the various pieces and artifacts contained in the burial cellar.

[1][6][7][8][notes 8] The Cà' Morta burial site was discovered on the southern outskirts of the city of Como, in Lombardy, in the continuation of an avenue: Via Giovanni di Baserga, in the Albate district.

[6][8][17][18] Nevertheless, a significant number of markers, such as manufactured products and ruins of mortuary structures, lend credence to the hypothesis of the re-employment of a protohistoric cemetery dating from the Middle to Recent Bronze Age.

On the whole, the infrastructures uncovered from the outcropping strata at the comasque site of Monte della Crocce[8][20] show a variety of architectural types: sometimes aristocratic, more frequently artisanal, agricultural, but essentially residential.

[notes 20][32] Consequently, given their chronological simultaneity and geographical homogeneity, some authors conclude that there is a highly probable cause-and-effect relationship between the two phenomena: on the one hand, the settlement of Celtic tribes at the precise point of Como / Ca' Morta, and on the other, the development of urban growth.

[8][35][36]In addition, multiple clues also discovered on the burial site, within the proto-urban remains,[notes 23] attest to a significant decline from the early 2nd century BC onwards.

[50][70] In addition to this remarkable piece of jewelry, excavation of the burial site revealed other ceremonial objects, such as "armilles"[notes 34] made of laminated bronze, and pearl earrings.

Further comparative analysis also revealed that the style and craft techniques required to produce many of the parts making up the ritual vehicles were, if not unicum,[notes 39] at least very similar (particularly with regard to chariot components such as balusters and body plates, hubs and hulls).

[82][6][85] Because of the number of concordant clues and evidence, the two teams of archaeologists were able to establish a probable interaction between the territory of the Vix / Mont Lassois oppidum and that of the Ca' Morta comasque site.

- Wenceslas Kruta[8]Other teams of archaeologists have been able to identify numerous chariot tombs, geographically dispersed across the western half of the area covered by the Hallstatt civilization[notes 41] and belonging to territories 400 to 500 kilometers distant from Ca' Morta.

These multiple occurrences of "chariot" funerary sites in the territory of the Celtic koinè[notes 42] present, like that of the Vix tomb, many elements in common with that of Ca' Morta.

[88][89][notes 44] Generally speaking, the archaeological finds at Ca' Morta, including the processional cart, are similar in nature and style to other items from Celtic burials and tombs of the Hallstattian period.

[6][7][90][87] In the particular case of Hochdorf, it is also remarkable that the ornamentation on the klinea (a type of ancient Greek bench)[notes 45][91][92][93] on which the deceased was laid, as well as the pendants with which his burial is associated, are typically Golaseccantes.

[95] In order to explain these obvious concordances between the Ca' Morta tomb and the burials of keltiké across the Alps,[notes 46][96][97] we need to focus on an important event in Comasque history.

Thus, the examples of the bronze "corded" cists and the chariot kline found at the Hochdorf burial site mentioned above corroborate the hypothesis of an export from the Golaseccian territory, and more specifically from the Como/Ca' Morta region.

[6][7][101][87]"This "Celtophony" of Como at the time of the Golasecca culture probably explains its development and wealth, as the agglomeration was the ideal intermediary in commercial traffic between the peninsula and the transalpine Celtic world."

- Wenceslas Kruta[32] In the same context, numerous tombs found in Hallstattian-type necropolises in the Bourges/Avaricum agglomeration in the Cher region[notes 50] display funerary furnishings containing artifacts with Eastern Golaseccian facies.

[102] A large number of so-called "chariot graves" in the Avaricum oppidum agglomeration, and in particular the Dun-sur-Auron burial site, attest to the intrinsically intimate nature of these two princely cities.

The elements making up the instrumentum of this cremation tomb suggest that the deceased was a woman, probably of North Italian stock with an Eastern Golaseccian cultural substratum[notes 54] and of princely social rank.

Individuals, men and women, moved to establish direct economic and cultural contacts, but also had to enter into relationships of hospitality, matrimonial, political and military alliances between the two regions."

In this context, Italian archaeologist Raffaele Carlo de Marinis describes Golaseccante society in the 5th century BC:"[...] the richest tombs at Golasecca are undoubtedly the female ones.

[124] In fact, ancient literary sources[notes 59][125][126] supported by numerous archaeological findings, tend to confirm that this Celto-Italian people settled in a geographical area covering the mid-northern part of Italy.

[124] Archaeological studies have made it possible to determine the exact location of the Orobii[127] within the Comascan territorial sphere during the whole of the First Iron Age, and have also confirmed the hypothesis that this tribe possessed a form of Golaseccante culture.

[128][124]In light of these elements, archaeological investigations unquestionably demonstrate that Celtic migrations, carried out in the life and fifth centuries BC, largely contributed to the ethnogenesis of the northern alpine tribes.

In a speech at the Collège de France, historian Daniele Vitali concludes his thesis on the role and testimonial value of the Prestino inscription (epigraphy written in Lepontic), at that time (5th century BC) and in that precise place:"From the point of view of a sociological interpetation, this "public" inscription, in a monumental context intended for the civic community of Como, gives the idea of the importance of the "Celtic" language as a means of communication for the Celtic-speaking (and literate) individuals of this "city" at the beginning of the 5th century B.C."

These were discovered and studied between 1955 and 1965:[12] The main architect of the archaeological research[notes 69] that identified and formalized the Ca' Morta necropolis[12][13] was the Italian archaeologist Ferrante Rittatore Vonwiller (1919 - 1976).

[12] The archaeologist was thus able to correlate them with a funerary establishment predating that of the Ca' Morta tomb, and attribute them to the chrono-cultural period characteristic of the central-septentrional territory of Lombardy (Comascan region) from the 11th to the 9th century BC, in other words, the Canegrate culture.